1. Introduction

ational identity is distinctive feature of one nation. Various studies have shown that a national identity is a direct result of the presence of elements which come from people's daily lives, namely: sense of belonging to one nation, national symbols, language, the nation's history, national consciousness, blood ties, culture, music, cuisine, radio, television, etc.

The national identity of most citizens of one state or one nation tends to strengthen when the country or the nation is threatened by outsiders or foreigners. The sense of belonging to one nation becomes stronger when an external threat threatens the citizens, so they feel that they have to unite with their fellow countrymen to protect themselves and fight against the common threat. National identity is a part of nation character which consists of 4 primary elements, namely: (1) national culture, (2) nationalism, (3) national ethics, and (4) national identity (Kartodirdjo, 1993). National identity can only be traced on nations' collective experiences or nations' history, because it is exactly what has been cristallized through certain periods and places (through history).

2. II.

3. Research Problems

In the process of strengthening the Indonesian national identity, modernization and globalization has brought some new cultural values such as materialism, consumerism, hedonism, etc. and these values can cause the deterioration of national identity. If the nation could not preserve and strengthen its identity, the following impact of modernization and globalization was that the nation would lose its national character, and have no strong power to protect its national cultures from total destruction.

National identity has to be strengthened because this is closely related to the developing and recharging nationalism which can be defined as an ideology to determine vision of the future, and the basic pattern of living and being. Antony D. Smith argues that all men will be nationalists in the day when they will recognize their identity, and nationalism is a brotherhood born among those who have grown and suffered together, and can pool their memories under a succession of common historical experiences (Smith, 1983: 22).

Based on the above mentioned problems, this study presents some primary research questions as follows: 1) Why does Semarang become a good medium of hybrid cultures?; 2) What kind of hybrid cultures does Semarang have?; 3) How do these hybrid cultures function as a medium of unity in diversity? III.

4. Discussion

a) The Formation of Semarang as a Maritime City i. Early Development of Semarang Maritime city is a city that is formed by all evidences that happened through the relationship between the land and the sea. Louis Wirth argued that a city is a huge and dense populated area, with heteregenous populations. Grunfeld says that a city should have non-agrarian economic sectors and many buildings that stand closely (S. Menno & Mustamin Alwi, 1994: 23-24). It is difficult to say when the formation of Semarang took place, because the written historical resources are very limited.

Amen Budiman used traditional historical resources, Serat Kandhaning Ringgit Purwa, Script KBG No.7 which shows that Semarang was founded by Ki Pandan Arang, the son of Pangeran Sabrang Lor, the second sultan of Demak. Acording to this sript, in 1398 çaka or 1476 AD, Ki Pandan Arang came to a firtile cape "Pulo Tirang" in which he spread islam among some ajars (ajar = Hindu-Budha preacher). This script shows also that there were 10 regions which had been conducted by ajars in Pulo Tirang, namely: Derana, Wotgalih, Brintik, Gajahmungkur, Pragota, Lebuapia, Tinjomoyo, Sejanila, Guwasela dan Jurangsuru. Ki Pandan Arang could change the beliefs of these ajars and the people of this land from Hindu-Budha to Islam.

Cerita Rakyat sekitar Wali Sanga explains that Ki Pandan Arang left the sultanate of Demak, together with his son, Pangeran Kasepuhan. From Demak they went to south-western of Demak, and finally they came to fertile land, namely Pulo Tirang. In this region Ki Pandan Arang built pesantren (Islamic school), in which so many people studied Islam, and because of the existence of this pesantren "Pulo Tirang" was then densely populated. In this fertile region, there were many tamarin (Javanese language: asem) trees, which grew very rarely (Javenese language: arang). Based on this story, from the words asem and arang, the name of Semarang was formulated.

These above stories told us that the formation of Semarang city ran parallel with the islamization and the political expansion of Demak sultanate. Before the arrival of Ki Pandan Arang, Pulo Tirang was certainly a fertile land, and it was already inhabited by those who had followed Hindu-Budha. Based on the point of view of this good assets of Semarang, it is undisputable that the sultanate of Demak would do political expansion to colonize this region.

Although Ki Pandan Arang had been successful in developing Semarang, the administrative power was performed by his son, Pangeran Kesepuhan, who took title Ki Pandan Arang II. This administrative power was given to Pangeran Kasepuhan after Ki Pandan Arang I died. His official innaguration as the first regent of Semarang happened in 12 Rabiulawal 954 H or May 2, 1547 AD. Pandan Arang II, the Semarang regional ruler, was also a merchant and syahbandar (civil servant who manages of port affairs). His profession could be learned from Babad Demak, edition of R.L. Melema (Budiman: hlm. 104-105). According to this Babad Demak, Ki Pandan Arang was a rich syahbandar, and because of his richness there were many merchants or traders who could borrow money from him. Based on this story, it could be supposed that at the middle of the 16th century Semarang had developed as a maritime city which had maritime trade and society.

Catatan Tahunan Melayu Semarang dan Cirebon (Graaf, et all, 1997: hlm 17 & 30) had given information that at the half of the 16 th century, there was shipping yard in Semarang with chinese human resources. During 1541-1546, this shipping yard had finished 1000 ships ordered by Sunan Prawoto (Sunan Mukmin), the son of Sultan Trenggono, the third Sultan of Demak.

Based on these above historical resources, it could be concluded that at the middle of the 16 th century Semarang had already developed as an administrative and maritime city which based economically on trade. These 2 characteristics were an important access of Semarang to become a good medium of the development of hybrid cultures.

5. ii. Early Inhabitans and occupation

The formation of Semarang as an administrative city (region) at the half of the 16th century indicates us that this region had a good geographic and economic assets for the heteregenous people who seek better living. The occupations of the inhabitans of Semarang at the beginning of the 16th century could be studied through the witness of Tome Pires, the Portugese sailor who came to Semarang at that time. According to Tome Pires, there were many traders and fishermen in Semarang (Brommer at all., 1995). More illustration about the occupations of Semarang people in the 16th century could be also known from Serat Kandhaning Ringgit Purwa script KBG Nr. 7, which expresses that a part of the inhabitants of Pulo Tirang at the time of Ki Pandan Arang I were fishermen (Budiman, 1976: 67 & 75).. Speelman, a gouverneur general of VOC in Semarang, said also that there were many fishermen who lived in kampung Kaligawe (Liem Thian Joe, 1931:pg. 14).

Based on Catatan Tahunan Melayu Semarang dan Cirebon (Graaf, et. all, 1998: 3) in the 15th century there was been a close relationship between Semarang and Chinese traders. Furthermore this historical resource told us that in the 15th century there had already existed muslims Chinese settlement in Semarang. In 1413 Chinese marine fleets from Ming Dynasty, led by Haj Sam Po Bo, repaired their ships in the shipyard in Semarang. This written historical resource could be taken as an evidence that in the 15th century shipping trade activities in Semarang was already excessive.

Besides traders and fishermen, another part of the inhabitants of the old Semarang city were craftsmen. This occupation could be traced from the toponymy, which told about the names of places that had been identified with the occupations of their inhabitants. Some places (kampongs) in the old Semarang city center had the names related to their occupations, namely: Sayangan (place of copper craftsmen), Pandean (place of iron craftsmen), Kampung Batik (place of batik craftsmen), Kulitan (place of leather craftsmen), Jagalan (place of slaughterer), Gendingan (place of Javanese music instruments craftsmen), Pederesan ( place of sugar palm tappers), Gandekan (place of gold craftsmen), Pedamaran (place of the trading of dammar /substance for colouring batik) and Petudungan (place of huts craftsmen) The names of these places (kampongs) in the centre of the old Semarang city indicates that in the 16th century, various handicrafts and craftsmen were already in existence. By the end of the 17 th century Semarang had been one of the prominent destinations of Chinese immigrants, besides Batavia and Surabaya. The arrival of the Chinese in Semarang at the end of the 17 th century had been motivated by trading relationship between China and South-east Asia regions. These immigrants came from southern coast of China, namely: Amoy, Canton, and Maccao. Ong Tae Hae, a Chinese came from Fu Kien, who ever been lived in Batavia (1783-1791), said that in Batavia there was a lodging "Loji Semarang", for the Chinese who would stay overnight until they met ships to go to Semarang Based on this witness, at 1783 there had been busy trade activities in Semarang (Onghokham, 1991: 86).

Before the arrival of VOC, the Chinese in Semarang obtained trust from the regent of Semarang to get the position of Syahbandar, who functioned to collect the taxes of imported and exported goods. The Chinese also got the monopoly of salt and rice trade. But, when the Dutch occupied Semarang region, the position of Syahbandar was taken over by VOC (Liem Thian Joe, 1931: 16-17). After VOC occupied Semarang, the Chinese took role in trade. According to the report of Speelman, the VOC gouverneur in Batavia, the Chinese in Semarang had a role in import and export trades, and were active in trading of salt, rattan, opium, and other goods (Brommer, 1988: 9).

6. ii. Inhabitants and Occupation in the Dutch Colonial Era

In the colonial era, the Chinese got a trust of the colonial government to handle the economic affairs. One of the evidences was that many Chinese people were recruited to work in economic fields such as cashiers in private or state companies (Semarangsche Kassiers Vereeniging Buku Peringatan 1912Peringatan -1952: 21 & 35): 21 & 35).

Based on this resources, it could be concluded that the Chinese became a part of the economic human resources in Semarang. Because of the huge amount of the Chinese population, Semarang took a notation as "the city of Chinese".

The arrival of the European increased the variety of the inhabitants of Semarang. The Dutch colonized Semarang at the end of the 17 th century, after Amangkurat II, the King of Mataram Kingdom, made agreements with VOC in October 1677, and 1678. These treaties had contented especially that that VOC got the domination in managing the incomes of Semarang ports, monopoly in trading of sugar, rice, textile, opium, and free taxes. These monopolies were the compensation from Mataram to VOC, because it could defeat Trunajaya, the regent of Madura, who opposed to Mataram (Ricklefs, 1981 The inhabitants of Semarang became more varied when the Malay, Arabic, and India trders arrived. There were also French, German, English, and African. The majority of Africans became the soldiers of Koninklijke Nederlandsch-Indische Leger (KNIL) (Brommer, loc. cit.).

The other foreigners were the Japanese. They came to Indonesia especially after World War I, especially for 2 important goals, namely economy and the expansion of Japanese military power. In the 3rd decade of the 20 th century, the people of Semarang had already awareness of the expansion of Japanese spread attractive but false slogan "Asia is for Asia", and they were aware that this slogan was for attracting the Javanese people to give total loyalty to the Japanese to win the war against western imperialists ("Indonesia Ditengah Revolusi Azia" dalam Api, 5 Agustus 1924 No. 2).

Based on the above information, it can be seen that in the Dutch colonial era, Semarang had been inhabited by many etnic groups. The Dutch colonial government deliberately made social stratifications of the inhabitants legalized in government regulations (regeering reglement) 1854 (Onghokham dalam Yoshihara Kunio (editor): 87). This stratification scheme had implication on the jobs' status of the people which can be explained as follows.

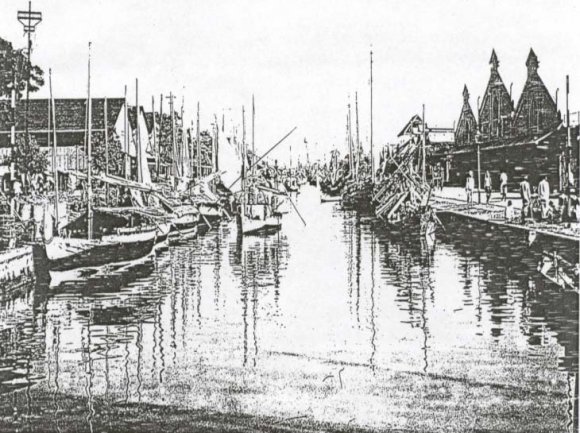

The lowest social level was the indigeneous people who worked as labours on manufactures, transportation, civil service. Helpers, craftsmen, pity traders, etc. The second level was the Chinese, divided in 2 groups, namely: (1) land holders, traders, other business men; (2) Geologically the port of Semarang was less benefial for shipping trade, as the continued process of sedimentation had caused the river which linked the city and the sea could not be sailed. To solve this problem, in 1868 some trading companies in Semarang carried out the dredging of Semarang river and during 1872-1874 they made also a new canal "Nieuwe Havenkanaal" (Kali Baru). Tis canal could be sailed by boats from Java sea to the center of Semarang city for unloading and uploading goods.

This new canal had provided a good access for foreign ships to come to Semarang port. The illustration of the increasing number of foreign ships which come to Semarang port can be checked in table presented below. Volume XIV Issue I Version I

At the beginning of the 20 th century, Semarang already had some private transportation companies, such as: "Semarangsch Stoomboot-en Prauwenveer", "Het Nieuw Semarangsch Prauwenveer", and "Kian Gwan's Prauwenveer".

To serve the shipping trade, in Semarang were also built ships which had larger loading capacities. At the end of the 19th century the average loading capacities of the ships in Semarang port was not more than 14 koyang (1 koyang = 1500-2000 kg., see A. Teeuw, 1990: 363), and the length of the ships 10 -20 meters. In the following years, the loading capacities of the ships reached 50-120 koyang, and the length and width of the ships: 27 meters and 5, 90 meters (J.J. Baggelaar, loc. cit.).

All of the above presented discussion gives us an explanation that since the middle of the 16th century Semarang already had heteregeneous inhabitants, and the consequence of this etnics diversity, Semarang had also hybrid cultures that will be discussed below. c) Semarang Hybrid Cultures i. Performing Art: Gambang Semarang Gambang Semarang is a traditional performing art which was born and officially developed in Semarang since the third decade of the twentieth century. This performing art is one of the forms of cultural integration between the Javanese and Chinese culture. There are controversial opinions about the origin of Gambang Semarang, it was from Jakarta or it was the original art of Semarang. But, apart from this controversy , Gambang Semarang has been actually possessed and developed by Semarang people until now, so this performing art is very potential to become Semarang cultural identity.

Gambang Semarang can be categorized as Semarang traditional performing art, born in Semarang in 1930, by the Chinese, Lie Ho soen, the member of gemeenteraad (Semarang city council). This performing art was performed at many events such as the Chinese new year in some Chinese temples, wedding events, and carnival "dugderan" (event to welcome the Ramadhan/Fasting month), events to welcome foreign tourists, etc.

The sequence of Gambang Semarang show can be explained as follows. The show begins with instrumental music and it is followed by some Semarang folksongs such as: "Empat Penari" (four dancers), "Gado-gado Semarang" (gado-gado = salad with peanut sauce). The following performance is dance with four primary movements, namely: lambeyan, genjot, ngondek and ngeyek. Jokes are often inserted between one and another step with a theme adjusted to the actual issues of society. This performance of Gambang Semarang ends with Semarang or Javanese folksongs, for example: "Lenggang Kangkung", "Semarang Tempo Doeloe", "Jangkrik Genggong", "Gado-gado Semarang."

Gambang Semarang can be mentioned as hybrid culture between the Chinese and Javanese cultural elements. Its music intruments consist of Chinese instruments (kongahian, tehian, sukong, and flute) and Javanese instruments (bonang, gambang, kendang, and gong). Formerly the dancers and singers of Gambang Semarang were Chinese. The female dancers and singers wore "sarong batik Semarangan" and "kebaya Encim" (woman's blouse-the front of wich pinned together, and embrodered with flora or fauna motifs), and the hair style is "gelung konde" (Javanese hair style). The musicians of Gambang Semarang are also hybrid, consisting of Javanese and Chinese musicians, and the songs presented in Gambang Semarang performance tend to be Chinese nuances.

How famous Gambang Semarang in 1940s era can be seen at the birth of the song "Empat Penari". This song is also the product of hybrid culture which consists of Chinese and Javanese creators. The melody was composed by Oei Yok Siang, and the poem was the creation of Sidik Pramono. These two creators were from Magelang, Central Java. Sidik Pramono was the musician of Perindu Onchestra in Magelang, and the song "Empat Penari" was sung firstly in 1940 in broadcasting studio "Laskar Rakyat" in Magelang by female singer Nyi Ertinah. Picture 4 : Sarong Batik Semarangan with plaited bamboo background and peacock motifs; these motifs were also inspired by Chinese cultural elements.

ii. Islamic ritual tradition: Dugderan and Waraq Ngendog

The Islamic ritual tradition "Dugderan" was firstly performed in 1881 by the regent of Semarang, Raden Mas Tumenggung Aryo Purboningrat. He was the creator of this "Dugderan" event to welcome the fasting month Ramadhan.

As a sign of the beginning of Ramadhan, there was a performed ceremony which began with the voice of "bedug" dug?, dug?, dug? (17 x) and the voice of cannon der?, der?, der?(7 x). Based on the voices of "bedug" and cannon the people of Semarang mentioned this event "Dugderan". "Bedug" is a traditional Javanese instrument to summon the people to do salat (Islamic prayer) time and cannon was an explosive weapon which comes from Europe.

This tradition has developed as folks fair and has been performed in Semarang town square (alunalun) one week before the fasting month began. This folks fair "Dugderan" is closed at the afternoon (usually at 4 o'clock), one day before the fasting month, with carnival which is accompanied with Semarang cultural symbol "Waraq Ngendog".

7. Warak Ngendog Tradition

Carnival "Dugderan" is accompanied by "waraq ngendog" tradition. "Warak Ngendog" is truely one of Semarang hybrid cultures. The creator of "warak ngendok" is very smart to mix cultural diversity in one symbol, namely an invented animal that looks like a goat with dragon head, gold furs, and has some eggs under his legs.

The word "warak" is from Arabic word "wara'i" that means holy. Some people suppose that the word "warak" comes from the name of arabic invented animal "borak" (= winged steed that carried Muhammad to heaven). As a whole the shape of "warak" looks like "Kilin", the Chinece invented heaven animal which has function to spread prosperity in the world, and the eggs under "warak" legs are the symbol of Javanese prosperity. The pictures presented below are the illustration of "Dugderan" carnival. Picture 5 : "Dugderan" carnival which was performed at one day before fasting month began.

iii. Indie Architecture The Europeans community in Semarang had also formed hybrid culture, among others housing style (Indische landhuis stijl), which usually expressed luxurious building with comfortable terrace and wide yard or park (Sukiman, 1996: 29) The house presented in the picture no. 7 also shows Indie architecture style with its characteristics, namely: terrace (for protecting the house from sunray and rain splash), enough ventilation and wide park with tropical trees.

8. d) Conclusion and Suggestion i. Conclussion

Along with the way of history, the Indonesian people can not be seperated from the influences of foreign cultures, and now there are many people regret the disappearing of Indonesian national identy because of the pressure of foreign cultures. Together with the expansion of these foreign cultures, there arises the degradation of the loving devotion to the national cultures, and the implication is that the Indonesian nation shall lose their memory of their past experiences which are important to protect and survive the Indonesian national state and national identity.

Semarang as a maritime city can become a model to strengthen national identity among the diversity of etnics and cultures. The cultural approach is an appropriate method to strengthen the national identy, because of its peace, tranquility and unity values.

Arts are the elements of culture which has important function as national identy, because they can show unique character and quality to the global society, and can become the media to unite the global nations. Through the arts (dance, local costum, song, drama, handicraft (example: batik), architecture, etc), people can express their feeling (happiness, appreciation), their wills and creations which are based on their local communities characteristics and cultural identities and through the arts brotherhood between nations can be developed.

ii. Suggestion National Identity should be strengthened continuously for some important objectives: 1) to show the national pride on nation own cultures, 2) to have national conciousness when facing the influences of other nations, 3) to protect and to survive the nation state and its nation.

The destrustion of national identity should not happened, if we always pay attention to and perform two primary principles as mentioned below: 1. Cultural identity that will be inherited by the next generation can not be allowed to live passively. The old values of the inherited cultural identity should be explored, analized, and should be developed with the new spirit of the new era, so they can be accepted and endorsed by the new generation. 2. If there is no such movement, it is sure the local or national cultural identity can not be alive or be totally destroyed.

Volume XIV Issue I Version I 45 ( D )

| Nation | 1850 People | % | 1890 People | % | 1920 People | % | 1930 People | % | 1941 People | % | |||

| Native | 20.000 | 72,99 | 53.974 | 75,83 | 126.628 | 80,12 | 175.457 | 80,56 | 221.000 | 78,93 | |||

| Chinese | 4.000 | 14,60 | 12.104 | 17,00 | 19.720 | 12,18 | 27.423 | 12,60 | 40.000 | 14,28 | |||

| Other Eastern Foreigners | 1.850 | 6,75 | 1.543 | 2,17 | 1.530 | 1,47 | 2.329 | 1,06 | 2.500 | 0,90 | |||

| European | 1.550 | 5,66 | 3.565 | 5,00 | 10.151 | 6,43 | 12.587 | 5,78 | 16.500 | 5,89 | |||

| Total | 27.400 | 100,00 | 71.186 | 100,00 | 158.029 | 100,00 | 217.796 | 100,00 | 280.000 | 100,00 | |||