1.

Preserve for Whom? The Contradictions in the Preservation of the Urban-Industrial Heritage in Campinas (SP)

Preservar Pra Quem? As Contradições Na Preservação Do Patrimônio Urbano-Industrial Em Campinas (SP)

Resumo-Neste artigo, analisamos a noção de patrimônio cultural no interior do processo de produção e reestruturação da cidade, compreendendo como historicamente as intervenções urbanísticas e arquitetônicas -tanto aquelas que objetivam a renovação das formas e funções urbanas quanto aquelas com a finalidade da preservação do patrimônio e da memória da cidade -estão implicadas, nos diferentes períodos. Nesse sentido, os projetos e as ações impelidas pelos agentes produtores do espaço de Campinas -o poder público municipal, os empresários (do ramo industrial, imobiliário, cultural, do comércio popular, dentre outros), os moradores (antigos e novos), as instituições e os grupos políticos de defesa do patrimônio -evidenciam os conflitos pelos usos, funções e apropriação material e simbólica da cidade.

Palavras-chave: reestruturação urbano-industrial; patrimônio cultural; urbanização. Abstract-In this article, we analyze the notion of cultural heritage within the process of production and restructuring of the city, understanding as historically urban and architectural interventions -both those that aim at the renewal of urban forms and functions as well as those with the purpose of preserving heritage and of the city's memory -are involved in the different periods. In this sense, the projects and actions carried out by the agents that produce the space in Campinas -the municipal government, businessmen (from the industrial, real estate, cultural, popular trade, among others), residents (old and new), institutions and political groups for the defense of heritage -show conflicts over the uses, functions and material and symbolic appropriation of the city.

2. Keywords: urban-industrial restructuring; cultural heritage; urbanization. ¿Conservar para quién? Las contradicciones en la preservación del patrimonio urbano-industrial en Campinas (SP)

Resumen-En este artículo, analizamos la noción de patrimonio cultural dentro del proceso de producción y reestructuración de la ciudad, entendiendo como intervenciones urbanas y arquitectónicas, tanto aquellas que apuntan a la renovación de formas y funciones urbanas como aquellas con el propósito de preservar el patrimonio y de la memoria de la ciudad -están involucrados en los diferentes períodos. En este sentido, los proyectos y acciones llevadas a cabo por los agentes que producen el espacio en Campinas: el gobierno municipal, empresarios (del sector industrial, inmobiliario, cultural, popular, entre otros), residentes (antiguos y nuevos), instituciones y grupos políticos para la defensa del patrimonio: muestran conflictos sobre los usos, funciones y apropiación material y simbólica de la ciudad.

3. Introduction

he organization of a new urban morphology -with the growth of new closed lots divisions and consumption equipment for the elites and the middle-class -, occurred combined to the former inhabitants taking off and the appropriation of the historical centers by the low-income population, by informal and popular commerce. The economical devaluation of the historical center is referred by the press and by the government as mere degradation; when we may still consider that this devaluation situation is the one that allows its appropriation by low-budget layers.

Treated under the sign of degradation, the historical areas of the city has been suffering from several urban interventions in order to preserve their memories and their cultural heritage. In Campinas, the relative success of the interventions upon the City Market and old buildings of the local aristocracy evidence the positive side of the heritage preservation, associated to the cultural consumption of the city; on the other hand, the incorporation of the so called urban industrial heritage: the old industrial and railways installments, the workmen villages, among others, has evidenced the difficulties in attaining the preservation goals, such as the contradictions of such practice.

In the same time, the exaggerated fear of losing the identity referrals, generalized and enhanced by the press, the active action of the heritage managers and the attention of the real-estate and cultural entrepreneurs seem to overlap the diversity of social demands, or at least seem to reproduce a fragmented view of the social space processes, making it easy for the dominant ideologies dissemination.

Our text will be divided in two parts. In the first one, we search to deconstruct the cultural heritage concept to the light of its historical interpretation, in order to point to its theoretical advances and practical limits. In the second part, we propose to explore an empirical case, in order to analyze the formation process and the conflicts in the preservation of the urban industrial heritage in Campinas -SP. And nowadays who wants to remember? Who needs historical memory -the uprooted, the immigrant, the history-less. The one whose life had the meaning of the duration of time taken away, of the after-life endurance. The one that lives the lack of history, such as need and deprivation. Who? The elders and the young. The ones that do not have left whom to leave the fragment's memories, therefore, meaningless. These, because they don't have what to inherit? Both doomed. One, to the task that, in the end of the life, looks meaningless (the fruits of the labor are out of their hands and of their lives; they are somewhere else). The remaining memory is not of the construction: it is of the products, as it would say Lefebvre, of the tools, of the streets and of circulation paths. The other, doomed to the emptiness of the lack of a job, of a place, of perspectiveremaining and prematurely excluded (MARTINS, 1992, p.17).

For whom to preserve? Is it a question that implies to enquire what is the local communities' involvement in the preservation and what use do they do of the cultural heritage? In national scale, where it really happens a "heritage democratization" or is it about more of the political decentralization and its fragmentation in new heritage specialization? In what way listing representative properties of the industrial heritage has insured the preservation of the memory of the workers? Having seen the current heritage models, is it possible to accomplish the preservation without promoting the gentrification 1 Before going any further, it is necessary to understand that the production of the social spaceregardless of the preservation policies, but, without a doubt, by them influenced -, is marked by the renovations and permanence that express the dialectic of the processes among society and space. In such perspective, the space-social distinctions and of the affected areas? 1 The gentrification process promotes the "nobility" and the revaluation of the old urban areas. According to Smith (2007), the central urban areas have transformed themselves in the last "frontier" of the urban economic restructuring, after decades of metropolitan dispersion, the old urban centers have become urban experimentation laboratories. The notion of frontier sends back to the capitalism advance primitive conditions over the wild areas of the West. In this way, the construction of a new ideological plan, produced by the mainstream press, serves to justify the violence of the interventions in the "historical" and "degraded" urban areas.

inequalities (the places) are the product (and the ways) of everyday practices, bounded to the labor and leisure, which are permeated of symbolic references that compound the identity of the social groups. These groups, however, are space production agents and, therefore, of the materiality and of the memory of the cities (CARLOS, 2007).

Before this assumption, at least two views are imposed: one associated to the political economy of the city, and another to the extent of the social memory and of the accumulated cultural heritage. The first contains the games of the market forces and is associated to the action or omission from the government. The second may be either inherited from the past or projected in the future. In this way, the urban landscape may or not be preserved, as it may as well be constructed with a given symbolic function. (SANTOS, [1987] 2002).

In this way, we understand that the preservation of the heritage is disposed in a constant tension between the social right and the social space increase in value dynamics, a deadlock immerse in contradictions.

The historian Madeleine Reberioux (1992), coming from the perspective that seeks to establish relations between place and memory, dedicates herself to purpose a history reading from the outlook of workers, women, farmers, immigrants, in the end, a history reading focused on the social groups that were threatened of extinction by the intensified transformations of the 1970's. In her perspective, the worker memory places would condensate the "scientific and technical culture, industrial and worker cultural heritage. In the end, it is where they occupy in their imaginary and what such place, such memory, can teach us" (REBERIOUX, 1992, 49-50) 2 2 The author purposes a classification of the places with worker memory, which are: the "worker solidarity places" (coffee shops, bars, worker associations, unions); "working places" (workshop, factory, plant); and the "symbolical places", "made symbolical by the will of winning the oblivion in which drowns not only the worker daily life, but as well as the struggle of the dominated" (REBERIOUX, 1992, p. 53).

. The memory places would reveal, according to the author, the contradictions between pressure and resistance, exploration and solidarity, hierarchy and insurrection contained in the direct relation between labor and capital. The author seeks to highlight the militant aspect of the worker memory places, she does, however, state: "It happens that there is only a proletarian past, when it is shared", what makes them interesting "is its presence in the worker memory, is what the interrogated workers tell us about it. In sum, it is the place that they occupy in their imaginary" (REBERIOUX, 1992, p. 49-50).

Simone Scifoni (2013, p. 5), when operationalizing the notion of worker memory places, argues:

In sum, comprehending the memory place from the outlook of the geographical analysis means to dialectically articulate the next order/distant order, the place/worldwide, the greatness/misery of the daily life, the individual/collective memory and, in the end, the voluntary and involuntary memory 3 It seems clear to us that the numerous studies about the history of urban growth and of the worker villages in São Paulo, as well as the inventories that deal with different architectures typologies of the factories and old inactive industrial spaces, indicate a great advance in technical and theoretical terms . The notion of worker memory places in a direct and indirect way, made their way to the current conceptions of heritage contributing with the conception of the industrial heritage. Taken as the documents of the labor world and of the industrial production, they would be in the same time representatives of the world architecture of the power and the struggles against the power (REBERIOUX, 1992; SCIFONI, 2013). In this way, there is the notion of memory place important contribution, for it seeks to overcome the material and immaterial duality, in the way that it operates the symbolical and the functional, the memory and their social uses. 4 In this way, according to Jeudy (2005), this old about to fade away have transformed itself into a living treasure, which activated a memory duty moved by a certain "heritage fetish". The author highlights that the creation of industrial museums would also be marked by the progressive scenario creation and the emptying of the industrial heritage content . These important studies are subsidies for the seal of cultural wealth connected to the world of the industry and the labor.

Beatriz M. Kühl (2010), in national extent, signs how much the studies related to the industrial archeology and to the industrial heritage were poor when related to the theoretical aspects of restoring. According to Rodrigues (2012), in practical terms, it is about, in the end, of a hard dislocation of the exceptionality for the daily life, which involves, once again, through our scope, questions related to the political economy of the city. To this author, the success of the cultural heritage would come from the commercialization of certain culture aspects, process that became generalized throughout the world. In his words (JEUDY, 2005, p.26), "The weapon of the heritage flows through itself a universal humanist form that allows the government to attain the general assent" 6 Harvey (2006) gives us some clues upon the contradictions in the current period when he mentions the importance of the symbolic capitalism and the local cultures while important factors of space distinction to attract investments . 7 . For Harvey, it is a new period, in which the urban governance and entrepreneurship would value from cultural aspects to investments attraction, specially related to the "new economy", to tourism and to the cultural consumption 8 In other words, it is about the denial of the heritage while space consumption and not the ways to accomplish citizenship. The notion of vindictiveness brings us other dimensions of the patrimonialization. It is understood from the idea of the retake of a threatened territory, starting from the idealization of the public spaces, by a supposed degradation. In this way, "the patrimonialization marks spaces", "segregates users", .

4. Volume XX Issue IX Version I

5. In

Costa's (2008) interpretation, the patrimonialization is the condition and the product of a "dialectic of destructive construction of the heritage", because it is about a "political action that subverts the 'spontaneous' preservation of the space and of the social relations when transforming the cultural heritage in a 'cultural industry potential product', that has the power to banalize by the progressive scenario creation" (COSTA, 2008, p. 162). Costa and Scarlato (2009, p. 25-26) synthesize: "We cannot separate the consecration of the heritage from the 'space evaluation' from the 'environmental evaluation' and from the 'territory formation'". 6 In the way attributed by Henry-Pierre Jeudy (2005), the patrimonialization produces a ratification of the social space when reproducing contradictory interests in the name of the right of memory. For Jeudy, the patrimonialization is a way for the production of the esthetic image of the city, where the spectacularization would be the positive face of the heritage preservation. On the other hand, by making such heritage attractive and desirable through the so called revitalization policies, the expulsion of the local populations would end in the disappearing of the "living aspect of the city", driving towards the petrification of the cities or turning them into museums. 7 Harvey (2006) analyzes the production of the new "monopoly rents" that are attained by the uneven geographical development, opposed to the homogenization promoted by the capital. The author mentions the cases of Barcelona, Rome, Berlin, among others, where the election of the symbolic capital emerged among conflicts for the space appropriation. 8 In the Latin American countries, this process started on the early 1990s. And it seems like, again, was up to us the incorporation of external models, that were transported to a social context in which the more immediate demands, such as living, accessibility, security, culture, are still to be attended to. ( "expels undesirable residents". Such retake, in the name of preservation, does not stop the social classes removed from these areas to return (process of counter vindictiveness), overall in virtue of the lack of continuity of the public policies (LEITE; PEIXOTO, 2009).

In this way, among ideological contradictions and cultural heritage practices, revealed at least partially, we will approach a specific case of preservation of the so called industrial heritage 9 III. Conflicts in the Preservation of the Urban Industrial Heritage in Campinas -SP .

According to Francisco (2008), the formation of a preservationist group in the city, the Yellow Fever Preservationist Group, led by Antonio da Costa Santos 10 , Luiz Cláudio Bittencourt and Sérgio Portella, is a big mark in relation to the heritage preservation of Campinas 11 . The group promoted a vigil and promoted a symbolic hug around one of the first factories of Campinas, the Lidgerwood Manufacturing Co. 12 A little earlier, with the initiative of fourteen people and under the leadership of the french Patrick Dollinger, the Brazilian Association of Railway Preservation (Associação Brasileira de Preservação Ferroviária -ABPF) was created in the year of 1977. Under the context of the highway culture, of the low investments on the railway section and of the scrapping of the railway heritage, the ABPF managed to, together with FEPASA, a deactivated railway branch to initiate activities of restoration of locomotives and abandoned , stopping the demolition of the building that was scheduled in the road network restructuring project of downtown (the construction of a tunnel that connects downtown to the Industrial Village), during the administration of the mayor José Roberto Magalhães Teixeira (1983-1988). 9 Even if Unesco, through its letters and recommendations, insists in the fragmentation and specialization of the concept of the cultural heritage, we utilize the concept of industrial heritage (or urban industrial) in a critical way, which means, in a way of restoring the unity of the concept. 10 Antônio da Costa Santos was known as ToninhofromPartido dos Trabalhadores -PT. In his trajectory as architect, university professor, and politician, he was the founding member of the Yellow Fever Preservationist Group, which took effective participation in the defense of the town's heritage, keeping a critical posture to the first actions of the CONDEPACC. Toninho was elected mayor in Campinas in the year of 2001 and was murdered months after that. In his administration as a mayor, elaborated a rehabilitation plan of the heritage for the central area of Campinas, that was not put into operation, but served to the succeeding projects. 11 The actions of the Yellow Fever started in the end of the 1970's. The group produced the first inventory in the city and requested the first registrations of value to the community protections to the state council of preservation, the CONDEPHAAT. 12 In 1990, the building was registered as value to the community by the CONDEPACC, municipal organ of preservation, and, after restoration, shelters the City Museum.

wagons. A heroic history, made with scarce resources and a lot of willpower of old employees and railway enthusiasts. Aggregated efforts that culminated in the creation of the railway museum "ViaçãoFérrea Campinas-Jaguariúna" in 1984 13 The CONDEPHAAT, state organ of cultural heritage preservation, listed the railway station of Campinasas a heritage site in the year of 1987 It is worth to highlight that the delimitation of the Historical Center by the CONDEPACC, in 1991, was heavily criticized by members of the Yellow Fever Group, because, according to opinions of their members printed in newspapers of the time, it did not correspond to the historical phases of the city. In Francisco's (2008) interpretation, initially, the actions conducted by the preservationist organ had a more punctual and emergency character, considering the risk of vanishing and disfigurement of cultural property in the city. The intense rhythm of the urban growth of Campinas and the pressure of the real estate speculators, in special in the center area of the town, demanded emergency measures from the CONDEPACC. 14 . However with the privatization of the company in the 1990's, the discharge warehouses, the workshops, the offices that served to the maintenance of the trains and of the railroad ended up abandoned, leading to the deterioration of the constructions. 15 13 Besides influencing the railway preservation in national scale, the big success of the ABPF was to manage to keep in activity a stretch of approximately 20 km between Campinas and Jaguariúna. Stretch that carries part of the coffee history, the railways and beginning of the industrialization of Campinas. Cultural heritage that was rescued by the initiative and will of the population. Visit: http://www.abpf.org.br/ 14 The former station of the Paulista Company of Railroads is part of a big railway complex that served as maneuver patio and sheltered diverse warehouses destined to the railway maintenance workshop. The train station for passengers that worked until the year of 2001 was built in the end of the century in the "Gothic-Victorian style, according to the British architecture standards", and served as stop between Campinas and Jundiaí, and Campinas and the São Paulo State countryside. (According to Resolution 9 of 82/4/15 of the CONDEPHAAT).

. 15 Despite of listing the station and the complex as heritage sites, in very short time they would become shelter of homeless, junk pickers, walkers, punks, drug addicts, etc. The entire railway complex of Campinas was listed as heritage site by the Council of Defense of the Cultural Heritage of Campinas -CONDEPACC, in the year of 1990 (according to the resolution 004/90 of 1990/11/27). Afterwards, a series of other complementary listings, based on inventory and

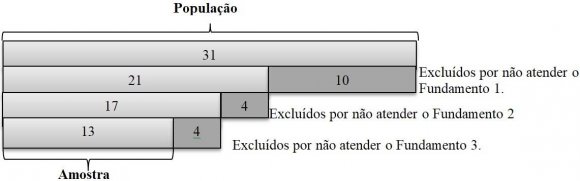

The station reform, occurred in the year of 2003, allowed that the station gained new functions. Currently, the Culture Station is the house of the Culture Secretary and shelters a professional forming center; has classes that provide arts, music, dancing courses, etc. Beyond that, the space became the stage of shows and cultural events in Campinas 16 However, the relative success in the preservation of the Culture Station and other mentioned properties contrasts with the conflicts for the preservation of their immediate surroundings. Even the recovered warehouses, that did not get a function, are deteriorating once again. On the top of all, listing the worker homes in the Industrial Village neighborhood . According to the analysis of Paes-Luchiari (2006, p. 57), the mentioned Culture Station, the 13 de Maio Street, the Palace of Tiles and the Cathedral, the defining marks of the "historical center", worked as the "flag ship" of the revitalization of the center of Campinas. 17 as heritage sites are considered fragmented initiatives and shortly contributed to the properties conservation 18 Figure 1 is a synthesis of the current state of conservation of part of the architecture heritage of the Industrial Village.

. Listing the villages as heritage sites did not stop that some specimens become ruins or demolished. requests from the technical organ of the Council of municipal preservation, were made. 16 As an example, in the Culture Station, occurred in the year of 2011 the Campinas DECOR -event about architecture and design -and the Cultural Turn Over in the years of 2008, 2013, 2015. 17 The Industrial Village neighborhood, the first industrial worker neighborhood of Campinas, was formed in the back of the Railway Station of the city, in the surroundings of two cemeteries, next to the Lazareto dos Morféticos and of the Hospital dos Varilosos, of the Matadouro Municipal and of the complex named Imigração. Since the end of the XIX century, the neighborhood has grown as the place that would shelter the workers of the railway, industries and tanneries in a place considered an unhealthy suburb of the town. According to our reading of the cartographic plants of the city, the installments of these "urban equipment" in the far areas of the city already signed the production interests of a segregated city. Later on, in this location to the south of the railway, other worker neighborhoods would raise: Fundão, Ponte Preta, São Bernardo, Parque Industrial, among others. (See annex). 18 The opening of a listing process for the Manoel Dias Village and the Manoel Freire Village (complexes of around 50 Gemini houses) in the year of 1985 by the CONDEPHAAT intensified the conflicts for the properties preservation. The villages had their demolition decreed in a newspaper article and, despite of the emergency character of listing request, in 1990, the process was still not defined. Due to the long time for the decision, the municipal council of preservation, CONDEPACC, opened a listing process to the villages. According to the listing of the architecture complexes as heritage sites, it is indicated the "recuperation and revitalization of the surrounds area of the complex", but nothing is said about the existing utilization 19 . In this way, the relatively low rate cost of the real estate in the surrounding area of the railway complex (which includes the popular center, the Industrial Village, Bonfim and Botafogo) attracts a low budget population that finds in them economical advantage and the possibility of gazing upon the proximity of the central area. 1797, 1842, 1878, 1900, 1916 and 1929. Map 2: Campinas: urban area formation (1797-1929) These are important data, since we consider the hypothesis that is through the continuity of the use that we manage to preserve the heritage. The maintenance performed by the local residents is what ensures to the houses its current conditions. The exchange of the tiles and roof are the objective way to the preservation of the listed properties. The new residents, northeastern migrants and their children, which nowadays inhabit the houses of almost a century old, mended and anchored the walls, switched doors and windows, raised bathrooms and knocked out walls, in order to guarantee the minimum dignity and well-being conditions.

6. Volume XX Issue IX Version I

In such scenery, about the listed complexes in the Industrial Village, we may name: the Architecture Complex Industrial Village, located in the margin of the Railway Complex; the Alferes Raimundo Street Complex; the Manoel Dias Village, the buildings of the called Immigration (and dozens of other real estates of historical value not listed) present themselves relatively conserved, because; in them, the continuity of the use ensured their current conditions.

However, in the year of 1995, there was the interdiction of the houses in the Manoel Freire Village (one of the listed complexes in the Industrial Village neighborhood) by the Urbanism Department of the city 20 Despite of the listing study, there was the noncompliance to the law by the government, which demolished properties that were under protection. What we realize in field is that there was the restoration of a few real estates of the old demolished railway village, . The residents were removed from their houses due to the risk of landslides and for the installation of a cultural center. The houses went through a long deterioration period, because they were abandoned and suffered with invasions and depredations. Here, we have an example, despite of the controversial, that it is through its use that the preservation of the heritage occurs; because the emptiness of the houses led to the ruin of the listed village.

The destruction of the Riza Village, railway village located in the interior of the Railway Complex, is another relevant case. The Riza Village, built in the 1940's, was demolished to give place to the new bus station and urban terminal of the city, the Campinas Multimodal Terminal, completed in 2008. Five constructions were kept and recovered to shelter services and commerce. According to the government speech in the printed newspapers, the action was part of an urban revitalization of the area process.

but the same, without new function, were depreciated and are deteriorating once again. Besides that, the relative isolation of the worker and railway villages, towards the urban surroundings, associated to the stigmatization of the area, still impose limits of visibility and recognition of the heritage 21 Recently, the municipal preservation council, CONDEPACC, listed 33 railway heritage representative properties as heritage sites in Campinas . A closer watch may find the railway houses inside the new bus station, but what do they represent with their doors and windows closed? Our analysis of the conflicts for the preservation of the industrial heritage serves to reveal the dispute for the production and appropriation of the spaces, from the material and the symbolic viewpoint. 22 . They are constructions, machinery, locomotives, wagons that are part of the railway complex mentioned. According to the council resolution, in the polygon of the area now called "Railway Cultural Park", was considered the old Lidgerwood factory (City Museum), but strangely the square in front to the "park" or the listed villages that compound its surroundings are not mentioned, and that are part of the same historical context of the city urbanization 23 We verified that a few punctual acts are being implemented by the government, but in a fragmented way.

For illustration purposes, the "square reurbanization", that, besides their positive aspect for the residents of the listed properties, it seemed to contribute even more to the increase in value of the new real estate ventures in the surroundings. Besides that, associated to such practices, we had the implementation of the "Zero Tolerance" program, which, since 2009, increased the police and the repression in the area. In a way that the appropriation of the historical area by the poor antagonizes with the image that they seek to print of the city . 24 21 In interview with the former residents of the Riza Village, we came to know that the privatizations of the railway in the 1990's and the mass dismissals contributed for the real estate deterioration, because, beyond the exit of the residents that gave their houses to relatives, many stopped receiving aid in the buildings maintenance. The impoverishment of the residents put them in a vulnerability state. Despite the increase of the police repression in the central neighborhoods, the area continue to be a way of surviving to the low budget population, beggars and local real estate for the poor, travelers and migrants. 22 According to the listing as heritage siteresolution nº 129 of 2014 June, 12th. 23 According to rectification of the resolution nº 130 of 2014 June, 12th, published in the Official Diary of the city in 2014 June, 16th. 24 The extensive area of the complex and its surroundings generates expectations of the real estate and transport sectors. The restrictions of the listings generate disputes and divide opinions. The projects of the High Speed Train -TAV Brazil and of the Intermetropolitan Train predict the utilization of the complex space, but not before new expropriations.

. While the ennoblement redefines the social significance of a place specifically historical for a segment of the real estate market, the decentralization redefines the real estate market in terms of a somewhere sense (ZUKIN, 1996, p. 209, highlights in the original).

In this way, the Complementary Law n° 2010 January 30th, created the Special Area of Reurbanization of the Multimodal Terminal Surroundings of Campinas -AERTM 25 It seems evident that the city projected by the government is priority over the real city, practiced by the low. Overall, because the government and the local press stigmatized the whole area, ignoring its origin and the multiplicity of uses in the area. The government makes use of the speech of the heritage preservation according convenient interests, including the execution of demolitions . The law predicts the restructuring of old warehouses of the railway complex, the reurbanization of extensive living areas, besides promoting the removals of junk pickers and slums of the central region (Industrial Village, Bonfim and Botafogo neighborhoods).

7. 26

The difficulties in the preservation of private properties also stop in the right of property that makes direct actions over the listed properties difficult. The neglect of real estate owners that are listed as heritage sites demands that the questions are resolved in other juridical stances. The preservation council possess the capability of surround prescriptively the properties so they accomplish their cultural role towards the society, but have no power upon the destination that the owner gives to his property. Beyond that, with the lack of information and non interest of the owners, there were no requests of exemption of taxes, nor the request for the transference of constructive potential of the real estates listed as heritage sites. The same may be . Still, the municipal council of preservation itself seems to reproduce this fragmentation, either by the institution of listing only in urgency character, or in the delimitation of the railway park without considering the worker villages. In this way, the train station has been reopened to the city, but the Industrial Village continues separated by the walls of the railway complex. For the residents of the neighborhood, the railway complex is still an enclave that isolates and brings down the value of the neighborhood.