1. Introduction

ccording to Hyland (2005a), academic writing has gradually changed its traditional tag as an objective, faceless and impersonal form of discourse into a persuasive endeavor involving interaction between writers and readers. This viewpoint regards academic writings as not merely producing texts that plausibly represent external reality, but also as using language to acknowledge, construct and egotiate social relations. In other words, academic writing is now widely acknowledged to be dialogical, involving interaction between a writer's authorial persona and the reader (Hyland, 2005a;Thompson, 2001). From this point of view, establishing an effective writer-reader interactive relationship is vital in academic writing.

The growing studies on the topic of establishing an effective writer-reader interactive relationship in academic writing, however, has focused on the ways that writers use language to project the stance, identity, or credibility of themselves, rather than examining how they enga

The present research focuses on the construction of writer-reader interactive relationship from ge with their readers. Meanwhile, considerable research on this topic was carried out mainly from the aspects of different disciplines, different sections of thesis writing, and under different language or cultural backgrounds. For example, some studies are about how various linguistic features contribute to the writerreader relationship (Bazerman, 1988;Hyland, 2000;Swales, 1990). the aspect of readers and in the single discipline of linguistics.

Based on the Model of Stance and Engagement (Hyland, 2005a) and a self-established corpus which contains 60 RAs from the international academic journal Language Learning, the present study aims to identify the distributions and categories of reader engagement.

2. II.

3. Theoretical Framework a) Model of Interaction (Model of Stance and Engagement

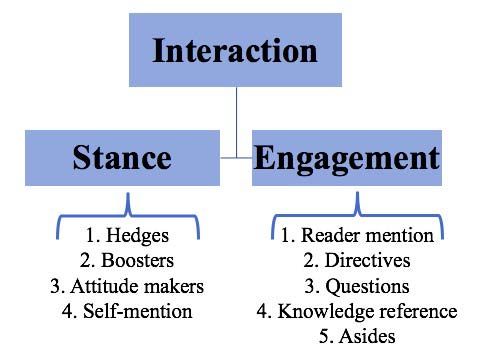

According to Hyland (2005a), the concept of interaction reflects the writer-reader interactive relationship in academic writing, which contains two perspectives---writer and reader. To observe and describe the interactive relationship, Hyland (2005a)

4. b) Definition and Purposes of Reader Engagement

Based on Hyland's (2001b;2005a) definition, reader engagement can be seen as an alignment dimension where writers "acknowledge and connect to readers, recognize the presence of readers, pull readers along with their arguments, focus readers' attention, acknowledge readers' uncertainties, include readers as discourse participants, and guide readers to interpretations".

In accordance with Hyland (2001b;2005a), there are two main purposes to writers' use of engagement strategies: the first purpose is to "adequately meet readers' expectations of inclusion and disciplinary solidarity" (Reader Pronouns and Interjections); the second purpose is to "rhetorically position the audience" (Questions, Directives and References to Shared Knowledge).

5. c) Ways and Markers of Realizing Reader Engagement

Reader engagement in academic writing can be achieved through the use of some resources including:

1. Reader Mentions: soliciting solidarity Reader Mentions can be defined as the direct reference to the reader with personal pronouns or other devices. Reader Mentions comprise: (a) second person pronouns and possessives (you, your); (b) inclusive firstperson pronouns and possessives (we, our, us); (c) indefinite pronouns (one, one's); and (d) items referring to readers (reader, the reader).

6. Questions: constructing involvement

Questions are explicit engagement features as they invite collusion with readers: addressing readers as someone with interest in the problem posed by the question, with the ability to recognize the value of asking it, and with the good sense to follow the writer's response to it (Hyland, 2002c). Questions contain: (a) direct questions and (b) rhetorical questions.

7. Appeals

to Shared Knowledge: claiming membership Appeals to Shared Knowledge is common in professional research writing where "academics seek to position readers within naturalized and unproblematic boundaries of disciplinary understandings" (Hyland, 2001b). Writers construct themselves and their reader as members of the same discipline or academic community by explicitly referring to the agreement.

8. Directives: managing readers

Directives are defined as utterances instructing or directing readers to perform an action, or seeing things in a way determined by writers. They may be performed by means of (a) imperatives; (b) modals of oblig 5. Personal Asides: intimating Sharedness ation and necessity directing readers to a particular action (must, ought to, should, have to, need to); and (c) predicative adjectives expressing necessity or signifycance (it is necessary/ essential / required to). By using Personal Asides, writers address readers directly through asides and interruptions to the ongoing discussion, which briefly breaks off the argument to offer a meta-comment on an aspect of what has been said. This device allows writers to intrude into the text, break off from the argument, and offer a comment that contributes more to a writer-reader relationship. Personal Asides comprise (a) comments and (b) explanations.

In the present study, the research focus is the use of the above five markers in linguistic RAs. Based on Hyland's (2005a) definitions and classification of reader engagement markers, the five markers are subdivided, which is shown in Table 2.1.

9. Indefinite pronouns

Thus, one cannot conclude that the FSL subjects were less accurate' than the other subjects, and therefore, responded more quickly in the visual condition as a speed/accuracy trade-off.

10. Items referring to readers

Some readers will want to argue that this is a comparative analysis of neighborhood asso-ciation's more than social movements.

11. Questions Direct questions

To what extent can AL features (lexical diversity, syntactic complexity, and decontextualization) be found in caregivers' input to children at the age of 4 years 2 months (4;2) and 5;10 at home and in school, and is this extent related to family SES and literacy? Rhetorical questions

How can these findings be reconciled? Our goal in this paper is to offer an explanation for these stylized facts.

12. Appeals to Shared Knowledge

Single word expressions Obviously, motivation is a key factor in both goal setting and goal attainment.

13. Multi-word expressions

Of course, the most frequent lexical bundles are suggested in a list form (on the right hand of the screen) as one of the tool's features.

14. Directives

15. Imperatives

Now consider, for both NS and NNS, the more crucial findings on regular verbs, where there was a significant anti-frequency effect.

16. Modals of obligation and necessity

Such transformations should be studied in terms of the semantic and ideological transformations they entail.

17. Predicative adjectives

It is important to explore the role of different contributing factors.

18. Personal Asides

19. Comments

And -as I believe many TESOL professionals will readily acknowledge -critical thinking has now begun to make its mark, particularly in the area of L2 composition.

20. Explanations

These are time pressure (as pressure increases, difficulty increases) and the degree of visual support provided...

21. d) IMRD Structure in Research Articles

Swales (1990) put forward the IMRD structure and explained it as, firstly, "research papers make the transition from the general field or context of the experiment to the specific experiment by describing an inadequacy in previous research that motivates the present experiment". Then, the Method and Results sections (subsumed under Procedure in Figure 2.3) continue along a narrow, particularized path, while the Discussion section mirror-images the Introduction by moving from specific findings to wider implication.

Specifically, the Introduction section, as the rhetorical section that motivates the study, includes a review of previous research. A primary function of the Introduction section is to make claims about statements from other research. Similarly, the Discussion section, as the rhetorical section whose primary function is to explain the statistical findings in non-statistical English, makes many claims about the research findings. The Results section describes the process of manipulating the data obtained from the Methods section and makes only limited claims about the statistical tests. The Methods section simply describes the process of obtaining the data, rarely makes claims about other statements (West, 1980).

22. III.

23. Methodology a) Research Questions

This study attempts to investigate the following research questions:

What are the features of reader engagement in linguistic RAs? 1. What are the features of reader engagement markers in different sections (introduction, method, results, and discussion) of linguistic RAs from the perspective of frequency? 2. Are there any significant differences in the use of reader engagement markers among the different sections of linguistic RAs?

24. b) Data Collection

The data collection in the present study consists of four steps. In the first place, 100 RAs were collected from the journal Language Learning from 2016 to 2017, through convenience sampling. 30 RAs in 2016 and 30 RAs in 2017 were selected randomly. Consequently, the corpus used in this study consists of 60 linguistic RAs from the journal Language Learning from 2016 to 2017. Table 3.1 shows the details of linguistic RAs used in this study. Then, the 60 RAs were transformed from PDF format to TXT format. Then, the 60 RAs were listed from No.1 to No. 60 (Appendix 3). Unrelated information like titles, authors' names, abstracts, key words, tables, figures, irrelevant examples, notes, references, and appendixes were deleted.

Thirdly, the 60 RAs were divided into four parts and the corpus were classified into four subsets: Subset 1 (Introduction), Subset 2 (Method), Subset 3 (Results) and Subset 4 (Discussion). Subsets 1 to 4 were transformed into four TXT files, which were then Fourthly, based on Hyland's (2005b) list of reader engagement markers, the reader engagement markers were identified and coded in the four subsets.

25. c) Identification of Reader Engagement Markers

All of the five reader engagement markers in the corpus are identified and classified according to the following criteria: 1. Reader Mentions A. Among the four categories of Reader Mentions, second person pronouns and indefinite pronouns are easy to identify from the text. B. However, for the reason that the use of first-person pronouns and possessives consists of two subcategories (inclusive and exclusive), and only the inclusive use belongs to reader engagement markers, whether the first person pronoun is inclusive can only be identified through the specific context. Usually, articles are written by more than one authors. If the first person pronoun is used in past tense, especially in the method section, it is unlikely to be inclusive but exclusive, which probably describes the process of the study which may involve more than one researcher. C. As for the items referring to readers, distingu Example 1: ishing those addressing readers from those mentioning readers is needed.

When identifying collocations, we also need to consider the distance between the co-occurring words and the desired compactness (proximity) of the units. Here, we can distinguish three approaches based on ngrams (including clusters, lexical bundles, concgrams, collgrams, and p-frames), collocation windows, and collocation networks.

(Subset 1, inclusive first-person pronouns and possessives) 2)

26. Questions:

The key to distinguishing direct questions from rhetorical questions was whether they require any answer or simply attract the readers' attention.

27. Example 2:

Can L2 listeners just as easily adapt to foreign accents? And does producing an accent facilitate adaptation more than listening to it does? In contrast to Ll speakers, who are unlikely to deviate from the norms of their language spontaneously, L2 speakers regularly deviate and may therefore show a production training advantage.

(Subset 1, rhetorical questions)

3. Appeals to Shared Knowledge: Both single word expression and multi-word expression are responsible for conveying the sense of certainty. The identifications of single word expression and multi-word expression are quite easy compared to the identifications of the other four categories of reader engagement markers.

28. Example 3:

One obvious possibility is that DDL was not different enough from traditional teaching in these parts of the world, and this was somewhat borne out by C/E designs producing the lowest effect sizes.

(Subset 3, single word expressions) 4. Directives:

A. Modals verbs of obligation and necessity were regarded as Directives and were distinguished from those expressing possibility. B. Predicative adjectives command or require the reader to do something and are regarded as Directives. While nonpredicative adjectives, which are intended to describe the importance or necessity of something, were distinguished from predicative ones.

29. Example 4:

We must therefore be careful not to automatically interpret larger values, as has been done often (see above).

(Subset 2, modals of obligation and necessity) An effective way to distinguish comments from explanations is, to add expressions like "I think" or "I believe" to see whether the new sentence makes sense, and then judge whether the asides are facts or opinions according to the common sense as well as the context.

30. Asides: Example 5: All were graduate students in applied linguistics and reported a great deal of experience with L2 pronunciation analyses (either via enrollment in a semester-long course on applied phonetics and pronunciation teaching or participation in L2 speech projects as research assistants). (Subset 2, explanations)

IV.

31. Results

32. a) Overall Distribution of Reader Engagement in Four Sections

The frequency distribution of reader engagement in linguistic RAs is revealed in Table 4.1 and Figure 4.1. To make the frequencies in four sections comparable, the frequencies are normalized to the occurrence per 10,000 words. As is shown in Table 4.1, reader engagement markers occur 2,224 times totally among 418,487 words. That is, there is a total of 53.1 reader engagement markers per 10,000 words in linguistic RAs. Reader engagement markers occur most frequently in the Introduction section (76.9 words per 10,000 words), followed by Discussion section (66.8 words per 10,000 words) and Method section (45.3 words per 10,000 words). The frequency of reader engagement markers in the Results section (32.0 words per 10,000 words) is lowest among the four sections. According to the results shown in Table 4.2, there is a significant difference between the frequencies of reader engag b) Distribution of Reader Engagement in Each Section ement markers among the four sections of linguistic RAs (X2=22.747, df=3, p<.001).

Based on Table 2.1, the frequencies of five reader engagement markers as well as their subcategories in each section are shown in Table 4.4.

Table 4.4 reveals that the frequency of Directives category is highest within four sections (172 times, 36.0% in Introduction; 291 times, 52.5% in Method; 175 times, 51.5% in Results; 445 times, 52.3% in Discussion), followed by Appeals to Shared Knowledge, Personal Asides, Reader Mentions, and Questions.

To observe whether there is a significant difference existing in the distribution of five engagement markers within each section, Chi-square Test for Goodness of Fit is carried out four times. The results are shown in Table 4

33. c) Distribution of Reader Engagement among Four Sections

Based on the four groups of statistics presented above, the frequencies (which are normalized to the occurrence per 10,000 words to make them comparable) of five reader engagement markers among four sections are summarized in Table 4.5.

Firstly, based on Table 4.3 and Table 4.5, whether there is a significant difference existing in the distribution of five reader engagement markers among the four sections can be observed. According to the results shown in Table 4.6, there is a significant difference in the overall distribution of five engagement markers among the four sections (X2=102.552, df=4, p<.001).

Secondly, it can be summarized from Figure 4.2 that the frequency of Directives category (102.8 times per 10,000 words) is highest among five reader engagement markers in linguistic Ras, followed by Appeals to Shared Knowledge (41.4 times per 10,000 words), Personal Asides (28.8 times per 10,000 words), and Reader Mentions (26.9 times per 10,000 words). The frequency of Questions (21.1 times per 10,000 words) is lowest among five reader engag ement markers. 4.5 also shows the distribution of each reader engagement markers among four sections. It is obvious that the category of Reader Mentions occur most frequently in the Discussion (12.5 words per 10,000 words). Questions occur most frequently in the Introduction (17.5 words per 10,000 words) and seldom occur in Method section. Appeals to Shared Knowledge occur most frequently in the Introduction (16.2 words per 10,000 words). Directives occur most frequently in the Discussion (34.9 words per 10,000 words). Personal Asides occur most frequently in the Method (9.4 words per 10,000 words).

Based on the above results, it can be summarized that Directives are most heavily used in four sections, both Questions and Appeals to Shared Knowledge occur most frequently in the Introduction; Questions seldom occur while Personal Asides occur most frequently in the Method; Reader Mentions and Directives occur most frequently in the Discussion.

Whether there is a significant difference existing in the distribution of each engagement marker among four sections are tested through Chi-square Tests. According to Table 4.7, there is a significant difference in the distribution of Reader Mentions among four sections (X2=9.429, df=3, p<.05) and Questions among four sections (X2=23.545, df=2, p<.001); while there is no significant difference in the distribution of Appeals to Shared Knowledge among four sections (X2=5.146, df=3, p>.05), Directives among four sections (X2=6.538, df=3, p>.05), and Personal Asides among four sections (X2=2.034, df=3, p>.05).

V.

34. Conclusions

The features of reader engagement in linguistic RAs can be concluded as: There is a total of 53.1 reader engagement markers per 10,000 words. Reader engagement markers occur most frequently in Introduction (76.9 words per 10,000 words). There is a significant difference of the frequencies in reader engagement markers among the four sections of linguistic Ras (X2=22.747, df=3, p<.001). The frequency of Directives category (102.8 times per 10,000 words) is highest among five reader engag

The present study has pedagogical implications for the teaching of reader engagement in linguistic academic writing. Firstly, there is a call for sufficient and appropriate training of EFL students on the use of reader engagement markers to improve their academic writing in linguistics. Secondly, EFL teachers ought to remind students that academic writing in the register of linguistics is a dialogue between the writer and the readers, and thus the writer should take account of the readers' background information, needs and expectations to build a sound relationship with the readers. Finally, EFL teachers are responsible to take note of the common mistakes made by students in using reader engagement markers and to teach how to use the linguistic devices in an appropriate way. ement markers. There is a significant difference in the overall distribution of five engagement markers among four sections (X2=102.552, df=4, p<.001). Besides, the distribution of five engagement markers are significantly different within each section (X2=109.466, df=4, p<.001; X2=268.079, df=3, p<.001; X2=234.765, df=4, p<.001; X2=600.722, df=4, p<.001).

| Engagement markers | Subcategory | Examples given by Hyland |

| Inclusive first person pronouns | In this extract we can note how the lecturer stresses | |

| and possessives | how he is trying to make things simple. | |

| Second person pronouns and possessives | That is, though you can see words, you cannot see ideas or content. If you cannot see content, you have no proof that it exists. | |

| Reader Mentions |

| Name of journal | Year of publication | Number of articles |

| Language Learning | 2016 2017 | 30 30 |

| In total | 60 |

| Subset Year | Subset 1: Introduction | Subset 2: Method | Subset 3: Results | Subset 4: Discussion | Total words |

| 2016 | 32,701 | 51,164 | 57,430 | 56,546 | 197,841 |

| 2017 | 29,525 | 71,321 | 48,913 | 70,887 | 220,646 |

| Total words | 62,226 | 122,485 | 106,343 | 127,433 | 418,487 |

| Sections | Total words | Frequency | Per 10,000 words |

| Introduction | 62,226 | 479 | 76.9 |

| Method | 122,485 | 554 | 45.3 |

| Results | 106,343 | 340 | 32.0 |

| Discussion | 127,433 | 851 | 66.8 |

| In total | 418, 487 | 2,224 | 53.1 |

| Section | Count | Expected count | Chi-square | df | Asymp.Sig. |

| Introduction | 76.9 | 55.3 | 22.747 a | 3 | .000*** |

| Method | 45.3 | ||||

| Results | 32.0 | ||||

| Discussion | 66.8 | ||||

| Note. *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001 | |||||

| Inclusive first person pronouns and possessives | Introduction 37 | Method 18 | Results 42 | Discussion 143 | Year 2018 | |

| Reader Mentions | Second person pronouns and possessives | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Indefinite pronouns | 6 | 6 | 9 | 16 | ||

| Questions Appeals to Shared Knowledge Directives | 32 Reader engagement markers 45.3 20 30 40 50 Items referring to readers 0 10 0 Frequency in total / Percentage Discussion Results Method Introduction 47 / 9.8% 60 Direct questions 91 Rhetorical questions 18 Frequency in total / Percentage 109 / 22.8% Single word expressions 98 Multi-word expressions 3 Frequency in total / Percentage 101 / 21.1% Imperatives 88 Modals of obligation and necessity 67 Predicative adjectives 17 Frequency in total / Percentage 172 / 36.0% Personal Asides Comm ents 3 Explan ations 47 Frequency in total / Percentage 50 / 10.4% | 66.8 70 0 24 / 4.3% 0 0 0 / 0% 120 4 124 / 22.4% 76.9 80 193 82 16 291 / 52.5% 175 / 51.5% 90 0 51 / 15.0% 7 2 9 / 2.6% 61 3 64 / 18.8% 127 38 10 6 1 109 40 115 / 20.8% 41 / 12.1% | 0 159 / 18.7% 13 23 36 / 4.2% 108 8 116 / 13.6% 171 216 58 445 / 52.3% 13 82 95 / 11.2% | Volume XVIII Issue XIII Version I ( G ) | ||

| Total | 479 | 554 | 340 | 851 | -Global Journal of Human Social Science | |

| Reader engagement markers | Frequency | Introduction | Method | Results | Discussion | In total |

| Raw | 47 | 24 | 51 | 159 | 281 | |

| Reader Mentions | Normalized | 7.6 | 2.0 | 4.8 | 12.5 | 26.9 |

| Questions | Raw Normalized | 109 17.5 | 0 0 | 9 0.8 | 36 2.8 | 154 21.1 |

| Appeals to Shared | Raw | 101 | 124 | 64 | 116 | 405 |

| Knowledge | Normalized | 16.2 | 10.1 | 6.0 | 9.1 | 41.4 |

| Directives | Raw Normalized | 172 27.6 | 291 23.8 | 175 16.5 | 445 34.9 | 1,083 102.8 |

| Engagement markers | Count | Expected count | Chi-square df | Asymp.Sig. | |

| Reader Mentions | 26.9 | 44.2 | 102.552 a | 4 | .000*** |

| Questions | 21.1 | ||||

| Appeals to Shared Knowledge | 41.4 | ||||

| Directives | 102.8 | ||||

| Personal Asides | 28.8 | ||||

| Note. *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001 | |||||

| Engagement marker | Expected count | Chi-square | df | Asymp.Sig. |

| Reader Mentions | 7.0 | 9.429 a | 3 | .024* |

| Questions | 7.3 | 23.545 a | 2 | .000*** |