1. Introduction

ealth is a basic necessity. Engagement in regular physical exercise is a vital part of a healthy lifestyle. Education has a profound impact on population health. Schooling affects health because it increases the efficiency of health production; that is, more educated individuals -produce better health from a given set of health inputs, however, schooling can also directly impact health outcomes through allocative efficiency (Grossman, 1972). Grossman explains that under this mechanism, more educated people produce better health outcomes because they choose different input allocations in comparison to those who are less educated. Specifically, it allows individuals to acquire more information about the impacts of health inputs (medical care, cigarettes, exercise, and so on), which alters the consumption of these inputs, health behaviors, and affects health outcomes.

2. H

Grossman further argues that although the impact of schooling on health is vital for economic policy in developing countries, the overwhelming majority of research to identify the health returns to education has been done using data from developed countries. Considering the health problems and the disease burden in developing countries, there is need to study their people's health. This is because as migration continues the disease burden becomes an American problem.

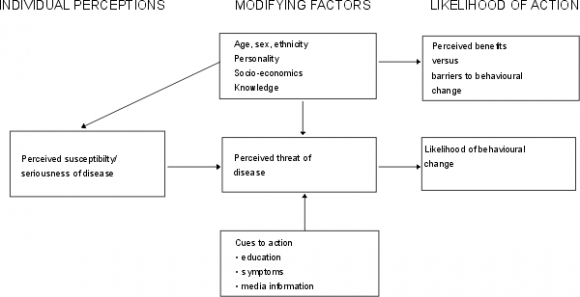

What motivates one to engage in healthy behavior? The Health Behavior Model (HBM) was formulated to respond to this and explain preventive behavior. Rosen stock (1974) observed that health interventions, promotions and disease prevention efforts had utilized it as a useful theoretical framework to understand what factors play into a person's perception of the risk of not engaging in health behavior. Though widely used in Western countries, the HBM has not been used much among Africans, especially in Kenya.

The HBM has four factors which serve as the key constructs of the model are perceptions of: (1)susceptibility; refers to an individual's perception that one will experience the dangers associated with the behavior or exposure in question (2) severity/ seriousness; refers to an individual's perception of the dangers a particular action or exposure can inflict. (3) barriers; perceived obstacles to engaging in a healthy behavior or forgoing an unhealthy one, and (4) benefits; refer to the perception of the rewards of a healthy behavior or avoiding an unhealthy one. An additional two constructs were added as also influencing behavior: (5) cues to action; strategies to activate readiness and (6) self -efficacy; which is confidence in one's ability to act (Rosenstock, Strecher and Becker, 1988).

An ongoing initiative of Healthy People 2020 is to "create social and physical environments that promote health for all." This includes increasing the number of adults who are at a healthy weight and decreasing the number of those considered obese. Despite the recognition that behavioral and medical health conditions are frequently intertwined, the existing health care system divides management for these issues into separate settings. This separation results in increased barriers to receipt of care and contributes to problems of under-detection, inappropriate diagnosis, and lack of treatment engagement (Richardson, McCarty, Radovic and Suleiman, 2017). been greater. According to Anderson ( 2018) in 2015, there were 2.1 million African immigrants living in the United States. This research studies the Kenyan diaspora in the US. It looks at health behavior perceptions and attitudes among men and women of Kenyan descent who live in three selected state; Alabama, Georgia and North Carolina. Using a Health Belief Model (HBM) questionnaire, the Kenyan immigrants were given questionnaires in meeting places. The HBM model has four main constructs are perceptions of: (1) susceptibility (2) severity/seriousness; (3) barriers (4) benefits. Results indicated that most Kenyan immigrants viewed improved health as the major benefit from physical activity (37.5%) followed by losing weight (23.2%) then increasing physical condition (13.1). The social change implications of the study are that the Kenyan immigrant population need to be encouraged to exercise and eat healthily. Results further showed that majority of the respondents (50.3%) fail to exercise due to lack of enough time, 13.8% due to lack of motivation while 10.2% due to inconvenience. As far as cue to action is concerned 28.4% of the participants indicated not fitting comfortably into clothing as the greatest cue followed by 24.8% of the doctor's recommendation while 12.1% indicated availability of exercise program as acue to action. The results reveal that there were no significant gender differences in health perceptions of barriers to action ( p= 0.564>0.05),of benefits to exercise (p= 0.604> 0.05, no significant difference in perception of cue to action (p= 0.159> 0.05) and risk susceptibility (p= 0.341>0.05). In particular, Kenyans living in Georgia were found to have better perceptions of benefits of exercise compared to those living in North Carolina and Alabama.

3. Statement of the Problem

There is a large gap in knowledge about the many Africans increasingly moving to the United states. This may be because they are homogenized with African Americans in literature or by sheer ignorance. Conflation of Africans and African Americans ignores the many differences between the two groups. This conflation has continued despite the historical and sociocultural literature differences that have been demonstrated by Ogbu (1983)

4. Conceptual Framework

Source; Glanz et al, 2002 IV.

5. Significance of the Study

Over 175million people, accounting for 3% of world's population, live permanently outside their countries of birth (UN 2002).Though the African population of immigrants to the United States is among the fastest growing there is a dearth of studies about them. Some of the reasons for this include their "invisibility" (Ghong, et al. 2007) and collation with African Americans (Wambua & Robinson, 2010). This collation has continued even when a lot of differences between them have been clearly shown.

Some of the African immigrants versus African-American differences include cultural, historical experiences and perspectives. Kenya's diaspora population is estimated at three million, unevenly spread all over the globe (Kenya Diaspora Policy, 2014). The majority of Kenyans living abroad are in the United States, Europe and Africa.

This study seeks to fill the knowledge gapabout Africans who are highly understudied. It looks at the health motivations and barriers of this population that has changed lifestyles from the "hardships" of Africa to the American "comfort". It investigates a population that has moved from a country where walking is a mode of transport which allowed exercise to a countrywhere cars are relatively cheaper, and walking is less.

V.

6. Review of Related Literature

This literature review will focus on existing research regarding the Health Belief Model and African immigrants. Venters & Gany, (2011) posited that as the number of Africans in the United States increases, there is a growing need to assess their health care needs and practices. They further argued that, although infectious diseases have been a traditional point of contact between health care systems and African immigrants, there wasa clear and unmet need to determine the risks and prevalence of chronic diseases.

The study used the Health Belief Model to examine beliefs and attitudes among Kenyans in the United States in a bid to understand why and how they take their health actions. The HBM has three major components: the individual's perception, the modifying factors which include demographic, psycho-social and structural variables and the benefits of taking preventive measures. According to Onega (2000), the HBM is a value expectancy theory with two values: the desire to avoid illness or to get well and the belief that specific health actions available to an individual would prevent undesirable consequences (Onega, 2000). Though one of the highly used measures in Western countries, the HBM has not as utilized among Africans and African immigrants to the United States. Buldeo & Gilbert (2015) used it to study HIV, AIDS and VCT knowledge among first year students at University of Witwatersrand in South Africa. They found that the students were willing to know their status, their peer influence was positive towards VCT, however, they found that some students did not access VCT due to personal fears. They concluded that the students' selfefficacy and cues to action could bring about a positive change in the future of the AIDS epidemic in the university context.

In Kenya, Volk & Koopman (2001), used the HBM to study condom use in Kisumu. They found that of the sample of 223 individuals who had engaged in intercourse the previous month only 20% of them had used condoms. Perceived barriers were the only aspect of HBM significantly associated with condom use. Vermandere et al. (2016), studied the use of HBM in predicting HPV uptake, focusing on the importance of promotion and willingness to vaccinate. They found that the perception of oneself as adequately informed was the strongest determinant of vaccine uptake and that susceptibility, self-efficacy, and foreseeing father's refusal as a barrier only influenced willingness to vaccinate which, however was not correlated with vaccination.

Asare, et al. ( 2013) studied condom use among African immigrants using the HBM. Their findings revealed that perceived susceptibility, perceived barriers, cues to action and self-efficacy were significant predictors of condom use in this population. Thus, they noted that this group was at a high risk of HIV/AIDS due to their risky behaviors, but they were inadequately studied.

7. VI.

8. Methodology

The purpose of this study was to attempt to close the gap in literature exploring the health of African immigrants to the United States. It utilized the Health Belief Model to specifically study Kenyans. This research, like the vast majority of research on health behavior, relied on self-report measures of behavior. It used a closed ended questionnaire. Asare and Sharma (2014) found the Cronbach's alphas and test-retest reliability for all subscales to be over .70.

The study used quantitative, cross-sectional methods. This data was collected through the dissemination of a questionnaire. The data collection took place in December 2017 and January 2018. A total of 168 questionnaires was collected.

The definition used of the Kenyan diaspora for the purpose of this research was deliberately kept vague. A number of Kenyan diaspora members have acquired American citizenship and have, as a result of this, had to give up their Kenyan citizenship. In

9. Data Analysis a) Demographic Characteristics i. Gender of the Respondents

The respondents were asked to indicate their gender in the demographic section of the questionnaire. Results in figure 1 below show that 50.3% of the participants were male while 49.7% were female. This means that the number of men and women was almost equal.

10. Figure 1: Gender of the Respondents a) Respondents' Education Level

Results presented in

11. d) Benefits to Exercise

The respondents were asked to indicate the major benefits they derive from physical activities. Results presented in Table 3 reveal that 37.5% of the participants indicated improved health as a major benefit derived from physical activities. In addition, 23.2% of the participants indicated losing weight while 13.1% indicated increasing physical condition. This implies that improved health is the major benefit that Kenyans in the United States derive from engaging in physical activities.

12. e) Barriers to Action

The respondents were asked to give major reasons why they fail to exercise. Results presented in Table 4 show that majority of the respondents (50.3%) fail to exercise due to lack of enough time. In addition, 13.8% of the participants fail to exercise due to lack of motivation while 10.2% due to inconvenience.

13. f) Cues to Action

The respondents were asked to give the major reason for getting to start an exercise program. Results presented in Table 5 revealed that 28.4% of the participants indicated not fitting comfortably into clothing. In addition, 24.8% of the participants indicated doctor's recommendation while 12.1% indicated availability of exercise program. This implies that the major reason why Kenyans in the United States start an exercise program is due to not fitting comfortably into clothing.

14. g) Risk Susceptibility

On the question of risk susceptibility results presented in Table 6 revealed that 18.3% felt that they were at risk of developing hypertension while 12.4% felt that they lacked strength. 8 presents Independent T-test results for gender differences in health belief perceptions among Kenyans in the United States. The results reveal that there were no significant gender differences in health perceptions of barriers to action (p= 0.564>0.05, no significant difference in perception of benefits to exercise(p= 0.604> 0.05, no significant difference in perception of cue to action (p= 0.159> 0.05) and no significant difference in perception of risk susceptibility (p= 0.341>0.05). 9 presents ANOVA results for state differences in perception of health beliefs among Kenyans in the United States. The results also reveal that there was a significant state difference in the perception of benefits to exercise among Kenyans in the United States (p value of 0.000< 0.05). This implies that Kenyans living in NC, GA and AL perceive benefits to exercise differently. In particular, Kenyans living in Georgia were found to have better perceptions of benefits of exercise compared to those living in North Carolina and Alabama. Further results were no significant state difference in the perception of barriers to exercise(p= 0.096> 0.05), no significant state difference in the perception of cue to action (p= 0.206> 0.05), no significant state differences in the perception of risk susceptibility ( p= 0.319>0.05. 10 presents ANOVA results for age differences in perception of health beliefs among Kenyans in the United States. Results reveal that there is no significant age difference in the perception of barriers to exercise (p value of 0.244> 0.05), no significant age differences in the perception of benefits to exercise (p value of 0.570> 0.05), no significant age difference in the perception of cue to action (0.645> 0.05) and no significant age difference in the perception of risk susceptibility (p value of 0.680> 0.05).

Results, however, reveal that there is a significant age difference in the perception of selfefficacy to exercise among Kenyans in the United States as supported by a p = 0.002< 0.05.In particular, it was found that Kenyans between the age of 36-45 years have a better perception of self-efficacy compared to other age categories. My expectation for this article was to provoke a discussion that would see a movement of populations from the traditional model of seeing illness on the machine-body. This model continues to ignore the major psychological part of illness. A wellness, health approach is highly needed to mitigate against future diseases not only for this population but for most world populations. The role of individual beliefs and values have a marked impact on physical activity engagement and adherence rates. They are predictors of current and future health behaviors in people. Results showed that majority of the respondents (50.3%) failed to exercise due to lack of enough time, 13.8% due to lack of motivation while 10.2% due to inconvenience. As far as cue to action was concerned 28.4% of the participants indicated not fitting comfortably into clothing as the greatest cue followed by 24.8% of the doctor's recommendation. Availability of an exercise program was indicated as a cue to action(12.1%). The social change implications of the study are that the Kenyan immigrant population in the United States need to be encouraged to exercise.

| III. |

| VII. |

| Gender | |

| Female,84 | male,85 |

| 49.7% | 50.3% |

| Response | Frequency | Percent |

| 18-25 | 29 | 17.2 |

| 26-35 | 39 | 23.1 |

| 36-45 | 52 | 30.8 |

| 46-55 | 34 | 20.1 |

| Above 56 | 15 | 8.9 |

| Total | 169 | 100 |

| c) State of Residence | ||

| The respondents were asked to indicate the | ||

| state they reside in. Results in figure 2 show that 47% of | ||

| the participants reside in AL, 30% reside in NC while | ||

| 23% reside in GA. | ||

| State | ||

| NC,51 | ||

| 30% | AL,80 | |

| 47% | ||

| GA,38 | ||

| 23% | ||

| Response | Frequency | Valid Percent |

| Losing weight | 39 | 23.2 |

| Feeling better psychologically | 16 | 9.5 |

| getting stronger | 9 | 5.4 |

| increasing range of motion | 1 | 0.6 |

| Increasing physical condition | 22 | 13.1 |

| improved mental alertness | 3 | 1.8 |

| Reduce risk of heart attack | 2 | 1.2 |

| Low blood pressure | 2 | 1.2 |

| Be with friends/social | 2 | 1.2 |

| Improved health | 63 | 37.5 |

| Feeling younger | 3 | 1.8 |

| Sense of accomplishment | 4 | 2.4 |

| Release of tension | 2 | 1.2 |

| Total | 168 | 100 |

| Valid Percent | ||

| not enough time | 84 | 50.3 |

| Inconvenience | 17 | 10.2 |

| Lack of transportation | 2 | 1.2 |

| Injury | 5 | 3 |

| Poor physical conditioning | 1 | 0.6 |

| Exercise is boring | 1 | 0.6 |

| Lack of facilities | 2 | 1.2 |

| Cost | 1 | 0.6 |

| Exercise interferes with work | 3 | 1.8 |

| Exercise interferes with social/family activities | 7 | 4.2 |

| Lack of motivation | 23 | 13.8 |

| too tired | 6 | 3.6 |

| too lazy | 13 | 7.8 |

| Illness | 1 | 0.6 |

| Bad weather | 1 | 0.6 |

| Total | 167 | 100 |

| Response | Frequency | Valid Percent | |

| Doctor's recommendation | 35 | 24.8 | |

| Advertisement television | on | 2 | 1.4 |

| Difficulty in climbing stairs | 4 | 2.8 | |

| Not fitting comfortably into clothing | 40 | 28.4 | |

| Advice from friends | 5 | 3.5 | |

| Advice from family | 5 | 3.5 | |

| Depression | 16 | 9.5 |

| Osteoporosis | 1 | 0.6 |

| Obesity | 13 | 7.7 |

| High blood pressure | 31 | 18.3 |

| Heart attack | 2 | 1.2 |

| Stroke | 1 | 0.6 |

| memory Loss | 1 | 0.6 |

| Bouts of anxiety | 4 | 2.4 |

| Inactivity | 49 | 29 |

| Arthritis | 5 | 3 |

| Stiffness and soreness | 4 | 2.4 |

| Cancer | 4 | 2.4 |

| Diabetes | 4 | 2.4 |

| Lack of strength | 21 | 12.4 |

| Being overweight | 13 | 7.7 |

| Total | 169 | 100 |

| h) Gender Differences in health belief perceptions | ||

| among Kenyans in the United States | ||

| Table | ||

| Health Perceptions | Gender | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | F statistics | P value |

| Barriers to Action | Male | 84 | 4.68 | 4.904 | 1.715 | 0.564 |

| Female | 83 | 5.13 | 5.242 | |||

| Benefits to Action | Male | 85 | 5.88 | 3.95 | 1.056 | 0.604 |

| Female | 83 | 6.2 | 4.096 | |||

| Cue to Action | Male | 70 | 4.71 | 3.195 | 2.36 | 0.159 |

| Female | 71 | 5.52 | 3.561 | |||

| Risk Susceptibility | Male | 85 | 8.28 | 4.954 | 0.487 | 0.341 |

| Female | 84 | 9 | 4.812 | |||

| Self-Efficacy | Male | 85 | 4.26 | 3.193 | 0.113 | 0.42 |

| Female | 84 | 4.65 | 3.172 | |||

| i) Differences in Health Perceptions among Kenyans in | ||||||

| the United States by State | ||||||

| Table | ||||||

| Sum of Squares df | Mean Square F | Sig. | ||||

| Barriers to Action Between Groups | 119.755 | 2 | 59.878 | 2.373 0.096 | ||

| Within Groups | 4138.71 | 164 | 25.236 | |||

| Total | 4258.47 | 166 | ||||

| Benefits to Action Between Groups | 242.242 | 2 | 121.121 | 8.162 0.000 | ||

| Within Groups | 2448.47 | 165 | 14.839 | |||

| Total | 2690.71 | 167 | ||||

| Cue to Action | Between Groups | 36.569 | 2 | 18.284 | 1.599 0.206 | |

| Within Groups | 1578.38 | 138 | 11.438 | |||

| Total | 1614.95 | 140 | ||||

| Risk Susceptibility Between Groups | 54.825 | 2 | 27.412 | 1.152 0.319 | ||

| Within Groups | 3950.16 | 166 | 23.796 | |||

| Total | 4004.98 | 168 | ||||

| Self-Efficacy | Between Groups | 38.55 | 2 | 19.275 | 1.928 0.149 | |

| Within Groups | 1659.37 | 166 | 9.996 | |||

| Total | 1697.92 | 168 | ||||

| j) Differences in Health Perceptions among Kenyans in | ||||||

| the United States by Age | ||||||

| Table | ||||||

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | ||

| Barriers to Action | Between Groups | 140.16 | 4 | 35.04 | 1.378 | |

| Within Groups | 4118.31 | 162 | 25.422 | |||

| Total | 4258.47 | 166 | ||||

| Benefits to Action | Between Groups | 47.581 | 4 | 11.895 | 0.734 | |

| Within Groups | 2643.13 | 163 | 16.216 | |||

| Total | 2690.71 | 167 | ||||

| Cue to Action | Between Groups | 29.18 | 4 | 7.295 | 0.626 | |

| Within Groups | 1585.77 | 136 | 11.66 | |||

| Total | 1614.95 | 140 | ||||

| Risk Susceptibility | Between Groups | 55.484 | 4 | 13.871 | 0.576 | |

| Within Groups | 3949.5 | 164 | 24.082 | |||

| Total | 4004.98 | 168 | ||||

| Self-Efficacy | Between Groups | 162.421 | 4 | 40.605 | 4.337 | |

| Within Groups | 1535.5 | 164 | 9.363 | |||

| Total | 1697.92 | 168 |