1. Introduction

ntuition is a method of making decisions that are both holistic and non-linear (Sinclair & Ashkanasy, 2005). Researchers may feel awkward with this conceptualization given the nebulous nature of the construct. The vagueness of the construct is a direct result of the natural presumption that knowledge is recognizable and valuable only when it is explicit, untainted by emotions, and open to cognizant idea and thoughtfulness (Hodgkin son and Sadler-Smith 2003). Mitchell, Friga and Mitchell (2005) opine that the utilization of intuition is challenging because there are excessive number of elucidations as to what constitutes intuition. There are also a myriad of elements that influence one's capacity to utilize it; the environment, brain organization (psychobiological perspectives), experience, training and the powerlessness to access intuitive information as and when required. Nevertheless, there is sufficient empirical support from the literature for an accord as to what constitutes intuitive decision making.

From a biological perspective, the intuitive process is a function of the neurological process within the basal ganglia. The basal ganglia are a collection of nuclei found on both sides of the thalamus, outside and above the limbic system, but below the cingulate gyrus and within the temporal lobes. Although glutamate is the most common neurotransmitter in the basal ganglia, the inhibitory neurotransmitter, gamma-Amino butyric acid (GABA), plays a significant role in the basal ganglia. Lieberman (2000) provided a social cognitive neuroscience approach to intuition, proposing that implicit learning processes are the cognitive substrate of social intuition. Lieberman (2000), after reviewing relevant neuro-scientific data, found that the caudate and put amen in the basal ganglia are central components of implicit learning, which prompts intuition.

The psychological perspective of intuition describes it as a process by which information, outside the range of analytical cognitive operations, is sensed and perceived in mind ascertainty of knowledge or feeling about the totality of an outcome (Sinclair & Ashkanasy, 2005). Mental constructs such as thoughts or ideas make up the intuitive process, which carries significant weights of certitude. It describes an instinctive utilization of implicitly stored knowledge linked to the rapid processing of information as the basis for reaching an apparently immediate decision. Thus, intuition is a process of instantaneously reaching a conclusion basedon little information rather than significantly more information and with feelings of certitude (Sadler-Smith, 2010).

Based on Sadler-Smith's (2010) and Mills' (2012) conceptualizations of the intuitive process, entrepreneurial intuition can be logically referred to as a spatial ability to make instinctive and instantaneous business decisions in the face of incomplete information and/or limited resources (Umukoro and Okurame, 2017). It is that part of entrepreneurial decision and action that is not based on extrapolated reason or logic (La Pira &Gillin, 2006) but on simplified mental models to piece together previously unconnected information. Thus, entrepreneurial intuition helps the individual to identify opportunities, invent new products and to assemble resources in starting and growing a business in a market with relatively unstable conditions (Sadler-Smith, 2010). Mills (2012) suggests that entrepreneurial intuition is expressed in dimensions of risk taking, creativity, proactivity and opportunity recognition. For instance, entrepreneurs with productive risk-taking impulses are able to explore and exploit unchartered business territories. Entrepreneurs with a healthy risk-taking spirit might sense opportunities where others do not and spot profitable trends well before the market is saturated (Lauriola, Levin, & Hart, 2007).Entrepreneurs with creative intuitions are successful in the development of competitive advantage. They can respond to current customer needs, anticipate future needs or challenges and develop new ideas, products or services. Entrepreneurs with proactive intuitions can recognize opportunities and preempt future challenges; they show initiative, take action, and persevere until they bring about meaningful change.

While there is a growing interest in the psychological antecedents of entrepreneurial intuition (Blume & Covin, 2011;Mills, 2012; Umukoro & Okurame, 2017), there is a dearth of studies on demographic differences in entrepreneurial intuition. There is, therefore, a gap in the academic literature concerning the role of age and gender in the development and utilization of intuitive skills among potential/nascent entrepreneurs. The importance of age and gender in the context of spatial abilities stems from a variety of theoretical assumptions such as Baylor's (2001) model of intuition and the hemispheric specialization theory by Mc Glone (1980). Both theories suggest that age and gender differences have significant roles to play in the variance of individual abilities to adopt intuitive skills. However, these theoretical assumptions have not received vigorous empirical validation, especially from culture-specific contexts. There is, therefore, a need for an empirical investigation of age and gender differences in entrepreneurial intuition, from culture-specific perspectives. Hofstede's (1983) dimensions of cultural values can be used to appraise cultural implications in the use of entrepreneurial intuition within a Nigerian context. Hofstede (1996) argued that culture is a fuzzy concept that can be viewed from two perspectives that seems inter-related and confusing. He stated that culture could be seen from a narrow perspective to mean "civilization" and in the broad perspective as "anthropology" which involves thinking, feelings and acting. Furthermore, culture is a combination of material and spiritual wealth designed by man through process of social and historical development.

Nigeria, like many other African nations, is a collectivist society, in which emphasis is placed on obligations towards in-group members (family and relations). In such a society, individuals are willing to sacrifice their individual needs and desires in order to have a sense of belonging, harmony, and conformity (Onwubiko, 1991). However, intuitive decision making is characterized by individualism, as it is dependent on subjective impulses from implicitly learned content. Therefore, the willingness to exploit intuitive abilities among Nigerian youths may be hampered by the collectivist nature of the society, in which decisions made by younger ones are expected to be ratified by experienced others before implementation.

Furthermore, high power distance often exists in collectivist societies. Hierarchy and power inequality are considered appropriate and beneficial in high power distance societies. It is quite common in high power distance cultures that the seniors or the superiors take precedence in leading, whereas the juniors or the subordinates must wait and follow them to show proper respect (Peretomod, 2012). Such high power distance exists in the Nigerian society where juniors and subordinates refrain from freely expressing their thoughts, opinions, and emotions within circles of their seniors. Therefore, the freedom to exploit and express intuitive abilities may be impeded by the presence of superior entities.

Additionally, gender roles are generally distinct and complementary, which means that men and women place separate roles in the society and are expected to differ in embracing these values. For instance, in patriarchal societies like Nigeria, men are expected to be assertive, tough, and focus on material success, whereas women are expected to be modest and tender, and focus on improving the quality of life for the family (Ekpe, Eja& John, 2014). Additionally, the educational and career success attained by a woman in African patriarchal societies is not often recognized, until it is capped by marriage and subordination to the authority of her husband (Onyejekwe, 2011). Thus, exploitation of intuitive capacities may be hampered among women who avoid the consequences of exploring their intuitive capacities on their expected role as wife and mother in the Nigerian patriarchal society.

2. II. Age and Intuitive Decision Making

In Baylor's model of intuition, expertise and availability of intuition are linked to immature and mature intuition. Figure 1 shows that the model is depicted by a curve that illustrates the variance in intuitive abilities from childhood, through adolescence, to adulthood. Baylor (2001) makes emphasis on findings from Choi's (1993) study in which students were asked to identify an increasingly more complete picture as soon as possible. Results showed that the mean reaction times for second graders who were exposed to the Westcott type of test were significantly higher than those of the kindergartners, fourth, and sixth graders.. Given these results, and similar results discovered by Schon (1983), Baylor suggests that children initially have intuitive understanding, but the analytic approach introduced during formal schooling conflicts with the intuitive thinking process, causing them to make mistakes.

Thus the curve in figure 1 bends downwards until children achieve more developed and schooled understanding which enables them to answer correctly again, utilizing now what Baylor (2001) calls higher order intuitive connections, given a corresponding increase in expertise. "Once one attains more expert knowledge structures, one develops the ability to figuratively 'see' different relationships and thus demonstrates mature intuition" (Baylor, 2001;p. 239). Hypothetically, the intricate issue of long or short periods of incubation may be partly explained by level of expertise.

3. III. Gender and Intuitive Decision Making

Some studies (Sherwin, 2003; Zaidi, 2010) have found gender differences in cognitive abilities such as perception, attention, memory (short-term or working and long-term), motor, language, visual and spatial processing, and executive functions. Generally, females have been found to show advantages in cognitive based activities such as verbal fluency, perceptual speed, accuracy and fine motor skills, while males outperform females in spatial, working memory and mathematical abilities (Sherwin, 2003). Using theories from social and neuro-psychology perspectives, numerous attempts have been made to explain the etiology and basic mechanisms for the expression of spatial ability among men and women. The hemispheric specialization theory proposes that gender differences exist in the anatomical structure of the brain and that such differences could explain sex differences in behavior. Supporting this perspective, it has been found that damage to certain areas in the right side of the brain lowers spatial ability of both sexes, but probably more so in men (McGlone, 1980). A review by Harris (1981) show that damage to the left side of the brain reduces spatial ability in women. Some social learning theories operate with tabula rasa models while others postulate stable early differences upon which societal forces exert an effect. According to tabula rasa models (e.g. Bandura and Walters, 1963;Michel, 1966) sex differences appear only because of separate cultural norms for boys and girls. Sex-appropriate behavior is reinforced according to norms. Generalization then takes place, so that situations similar to those in which the reinforcer occurred will also promote sex-typic behavior. According to social learning theory, the child may also copy the behavior of the same-sex parent through observational learning and generalize these experiences. Three implications of such social learning theory are that (i) only behavior shaped by reinforcement will appear (ii) behavior can be changed immediately at any time and without restrictions provided the reinforcing conditions are changed, and (iii) children will resemble their same-sex parent more than their opposite-sex parent. Research investigating age differences in emotion and cognitive ability in decision making are inconsistent (see Strough, Parker &Bruine de Bruine 2015; Mikels, Shuster, & Thai, 2015). If older people compensate for age-related cognitive declines by relying more on quick gut reactions, then older age may be associated with a decision-making profile focused on intuition and spontaneity rather than rationality. A study of undergraduates showed the opposite-older age was associated with reporting a less intuitive style (Loo, 2000). However, Bruine de Bruin, et al, (2007) found that older age in community-dwelling adults was associated with a greater likelihood of reporting both rational and intuitive styles. Discrepant findings could reflect differences in samples, with college education affecting the degree to which people rely on rationality and intuition.

Social learning theorists often stereotype women as "intuitive" and men as "rational". However, empirical research investigating gender differences in reports of intuitive and rational decision-making styles yields mixed results. For instance, in Sadler-Smith's (2010) findings, undergraduate women are more likely than men to report intuitive styles. Sinclair, Ashkanasy & Chattopadhyay (2010) used a mood induction that asked people to describe feelings about winning or losing a competition. Women reported using more intuition, and men reported using more reason. Also, La Pira and Gilin (2006) conducted a gender based study on intuition among entrepreneurs in Australia and found that females had an average score lower than their male counterparts, supporting the hypothesis that women are likely to be more intuitive than men (

4. a) Hypotheses

Based on the theoretical and empirical suppositions derived from the extant review of literature, the following hypotheses were stated and tested in this study:

1. There will be a significant main influence of age on entrepreneurial intuition among potential youth entrepreneurs. 2. There will be a significant main influence of gender on entrepreneurial intuition among potential youth entrepreneurs. 3. There will be a significant interaction influence of age and gender on entrepreneurial intuition among potential youth entrepreneurs.

IV.

5. Methods

The study employed a cross-sectional research design. The independent variables of the study are age and gender while the dependent variable of the study is entrepreneurial intuition. Age was dichotomized into young and old; gender was dichotomized into male and female. Participants consisted of youth corps members in selected National Youth Service Corps (NYSC) orientation camps within Southwestern Nigeria. The National Youth Service Corps, established by degree 24 of May 1973, is a scheme established to promote the ideals of national unity and promote national economic, development through mobility of labour in the formal and informal sectors. Nigerian graduates, not more than 30 years of age, from universities, polytechnics and other local or foreign degree awarding institutions are eligible to serve. The study participants comprised 780 (48%) male corps members and 846 (52%) female corps members. Their ages ranged from 19 -30 years with a mean age of 27 years (SD=1.87).

6. a) Measures

Age and gender were measured at ordinal and nominal levels as demographic factors. A culturally relevant entrepreneurial intuition scale was developed by the researchers was used to obtain data from the participants. A critical first step was to develop a precise and detailed conception of the target construct and its theoretical context. To articulate the basic construct as clearly and thoroughly as possible, it was necessary to review the relevant literature to see how others have approached closely related constructs that describe entrepreneurial intuition. Also, other entities from which the target was to be distinguished was examined. The brief, formal description of entrepreneurial intuition was conceived as "a spatial ability to make instinctive and instantaneous business decisions in the face of limited information and/or resources"

Having identified the scope and range of the content domain, the actual task of item writing commenced. Items that were related to the four dimensions of entrepreneurial intuition as conceptualized above were obtained via a review of relevant literature and adaptations of items from closely related constructs. Selections and adaptations of items were tailored towards the target population of the study. The researcher also carried out key informant interviews (KII) with successful entrepreneurs in order to generate more items. Successful entrepreneurs (who ran a medium or large sized enterprise for at least ten years, as their only source of income) were interviewed. Questions based on the objective of the pilot study were structured in an interview guide. A thematic analysis of the transcribed responses was carried out from which items were drawn based on over-arching themes. After a thorough check for redundancy, the items generated were subjected to face validity and content validity by experts in the field of psychology comprising selected postgraduate students and lecturers in the University of Ibadan. Only items that received unanimous support were included in the scale. A total pool of 52 items was finally drawn at this initial stage.

The 5-point likert scale format ranging from 'Not True of Me=1' to 'Very True of Me=5' was adopted for this scale. The 5 point likert scale is one of the most common response formats and is commonly used when measuring opinions, beliefs, and attitudes. Some of the Items were negatively worded to cater for agreement bias. The 52 items were structured into a questionnaire format and distributed in hard copy to a selected set of 250 youth corps members. Item responses were subjected to data analysis for item discrimination, factor analysis, reliability and construct validity of the scale.

Item discrimination of the 52 items of the scale indicated that 31 items had corrected item-total correlation below .30, and were therefore deleted from the scale. A confirmatory factor analysis of the remaining 21 items was performed to test whether measures of the construct were consistent with the researcher's understanding of the nature of the construct (or factor). All items loaded significantly on their constructs (p<.001), with weights ranging from .51 to .83. The items were sorted into entrepreneurial intuition dimensions of ingenuity (6 items), risk propensity (4 items), preemption (5 items) and opportunity recognition (6 items). The reliability analysis of the entrepreneurial intuition scale produced a Cronbach alpha of 0.85.

In order to test the convergent validity of the scale, an additional construct was included in the model; Entrepreneurial Attitude. To achieve validity of the scale, responses from the 21-item entrepreneurial intuition scale (EIS) was correlated with an abridged version of the Entrepreneurial Attitude Orientation Questionnaire (EAOQ) developed by Huefner, Hunt, & Robinson (1996). A Pearson's Product Moment Correlation analysis between EIS and the EAOQ showed that there was a significant positive correlation between entrepreneurial intuition and entrepreneurial attitude (r=.223; p<.05).

V.

7. Results

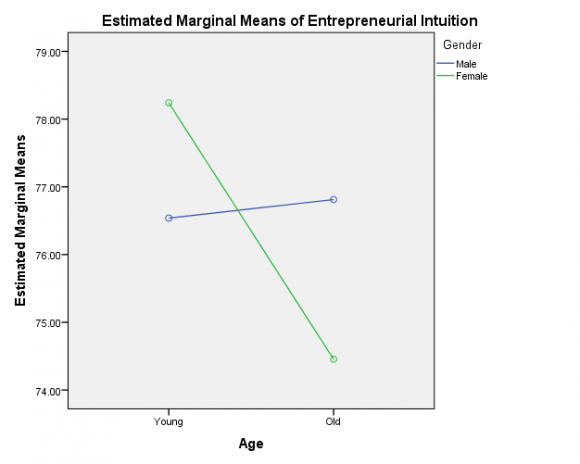

Following the completion of the data collection, the questionnaires were coded, scored and inputted into an SPSS software program. Both descriptive and inferential statistics were employed in the data analysis of the study. Frequency tables were used to describe the demographic information of participants. A factorial ANOVA was used to test the three hypotheses stated in this study. Results of this analysis are presented in Table 1. Results in Table 1 show that age [F (1,1618) =5.151; p<.05] had significant main influence on entrepreneurial intuition with an effect size of 3% while gender [F (1,1618) =.178; p>.05] did not have significant main influence on entrepreneurial intuition. The table also showed that age and gender interacted significantly to influence entrepreneurial intuition [F (1,1618) =6.883; p<.05] with an effect size of 4% among the study participants. Based on these outcomes, hypotheses 1 and 3 of the study were supported while hypothesis 2 was not supported. Further post hoc analyses were carried out to determine the direction of influence among the significant outcomes. Results of the post hoc analyses are presented in Tables 2 and 3. Results from Table 2 showed that there was a significant difference in entrepreneurial intuition between younger and older participants t(1620)=2.44; p<.05.

The results imply that younger potential entrepreneurs exhibited higher levels entrepreneurial intuition than their older counterparts. Results of the pairwise multiple comparison showed that entrepreneurial intuition mean differences of 2.00 (or more) among paired groups were significant (x? -diff?±1.70; p<.05) while entrepreneurial intuition mean differences of 1.43 (or less) among paired groups were not significant (x? -diff?±1.18; p>.05).

8. VI.

9. Discussion of Results

Results of this study showed that age plays a significant role in entrepreneurial intuition indicating that entrepreneurship interests may peak during nascent periods of growth and create a higher propensity to explore a wider range of career options. This conclusion is corroborated by Baylor's model of intuition which asserts that young children, who have presumably less exposure to linear, logical thought processes, are more naturally inclined to intuition and can be more easily trained to be intuitive thinkers than their older counterparts (Noddings & Shore, 1984). From a practical point of view, the use of intuition is a better option in the face of limited entrepreneurial experience among nascent and potential entrepreneurs. However, the rightness or certitude of such decisions may be dependent on implicitly learned contents or optimistic expectations. Correspondingly, a person may lose the experiential freedom of immature intuition when he or she develops more advanced knowledge structures as age increases.

Some entrepreneurial related studies have produced results that highlight the importance of age in entrepreneurship. For instance, Parker (2009) found that age and level of entrepreneurship education are considered to be important factors of entrepreneurial traits. Sahut, Gharbi and Mili (2015) who examined the impact of age on entrepreneurial intention also found a negative relationship involving age and entrepreneurial intent. Similar studies suggest that there is a positive impact of entrepreneurship education at early stages in life on self-employment probability (Blanch flower, 2000; Mustapha and Selvaraju (2015) who reported that gender was not an important factor in entrepreneurially oriented traits. The finding that age and gender interacted to significantly influence entrepreneurial intuition in this study implies that age plays an important role in the relationship between gender and entrepreneurial intuition. According to the outcomes of this study, younger female participants ranked highest in the expression of entrepreneurial intuition. In justifying this outcome, the increasing sensitization for gender equality and female empowerment in typical African societies, has begun to spur young female entrepreneurs to adopt more innovative ways to break through the glass ceiling in a male dominated labour sector.

One of the ways by which nascent female entrepreneurs have begun to make significant impact in entrepreneurship careers is to boycott the principles of rationality in business decision making, and rely more on quick gut reactions characterized by intuition and spontaneity (Larwood & Wood, 2007). However, the decrease in expression of entrepreneurial intuition among older females in the Nigerian society may be associated with cultural norms of collectivism, power distance and patriarchy in the society, which pressures females to conform to societal expectations of subordination and deference through the institution of marriage (Manser & Brown, 2000;Marthur-Helm, 2002, Umukoro & Okurame, 2017). Similar studies have supported the assertion that younger women are likely to be more intuitive than men (Ashkanasy & Chattopadhyay, 2010; La Pira and Gilin, 2006; Sadler-Smith, 2010).

10. VII. Conclusion and Recommendations

The results of this study support theoretical suppositions that age and gender play significant roles in the expression of entrepreneurial intuition among nascent entrepreneurs. Specifically, the results suggest that entrepreneurial intuition is highly projected among younger individuals. It is therefore recommended that intensive and comprehensive entrepreneurship training, with modules for enhancing intuitive skills, be incorporated in all categories of secondary and tertiary institutions. Such training should also be directed at youths in their teenage/adolescent years through early adulthood; as interest in entrepreneurship may be peaked during this period of growth.

| Source | Type III SS | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | ? |

| Age | 1141.002 | 1 | 1141.002 | 5.151 | .023 | .003 |

| Gender | 39.496 | 1 | 39.496 | .178 | .673 | .000 |

| Age * Gender | 1524.817 | 1 | 1524.817 | 6.883 | .009 | .004 |

| Error | 358432.907 | 1618 | 221.528 | |||

| Total | 9848238.000 | 1622 |

| Age | N | Mean | S.D. | df | T | sig |

| Younger | 636 | 77.6038 | 13.73565 | |||

| 1620 | 2.44 | .015 | ||||

| Older | 986 | 75.7505 | 15.62299 |

| 17 | ||||||

| Volume XVII Issue VIII Version I | ||||||

| ( A ) | ||||||

| Age | Gender | Mean | Std. Error | 95% Confidence Interval Lower Bound Upper Bound | ||

| Younger | Male Female | 76.538 78.241 | .965 .746 | 74.645 76.778 | 78.430 79.705 | |

| Older | Male Female | 76.812 74.455 | .639 .706 | 75.558 73.069 | 78.066 75.840 | |

| Results from Table 3 show that younger female | entrepreneurial intuition (75.84). The results are | |||||

| participants reported the highest mean level of | graphically illustrated in figure 2. | |||||

| entrepreneurial intuition (79.71) while the older female | ||||||

| participants reported the least mean level of | ||||||

| A B | C | D | Mean | |

| A | -1.70* 0.27 2.08* 76.538 | |||

| B | - | 1.43 3.79* 78.241 | ||

| C | - | 2.36* 76.812 | ||

| D | - | 74.455 | ||

| *The mean difference is significant at the .05 level | ||||

| Key: A=Younger Male | ||||

| B=Younger Female | ||||

| C=Older Male | ||||

| D=Older Female | ||||