1. Introduction

ver the last decade, the economic debate around non-renewable resources has mainly focused on the trade-off between the short-term challenges of managing volatile resource revenue and the long-term objective of sustainable economic development. When it comes to extractive industries, particularly the oil and gas sector, these concerns are of major relevance due to the importance of the sector for many economies. Against a backdrop of contradictions and hard choices, local content is considered as an attractive alternative to overcome this challenge (Morales, M.; Herrera. JJ.; Jarrín, S. 2016).

Local content is defined as the extent to which the output of the extractive industry sector generates further benefits to the domestic economy beyond the direct contribution of its value-added through productive linkages with other sectors (Tordo &Anouti, 2013). Generally, these linkages are created through purchase of domestically supplied inputs, labour or local skills and knowledge transfer (Auty 2006 However, if local content is the better alternative for oil and gas countries to reach local development, why does every oil and gas producing country not adopted a clear local content strategy yet? During the path of the development and implementation of a local content policy, countries face certain challenges and need to comply with several previous conditions. In that sense, it is a challenge for policy makers to establish the right local content policy for their countries to reach positive local content outcomes. Local content outcomes are understood as the results achieved in a country in terms of generation of local employment, skills development, investments and participation of the national industry along the oil and gas value chain.

Countries that adopt local content as a development strategy for their extractive sectors usually start by developing local content frameworks (policies, laws and contracts). While a well-designed local content framework is a valuable starting point, there are other factors that shape their successful implementation (Aoun and Mathieu 2015). Mapping these factors presents a challenge for scholars and policy makers due to the varying context that oil and gas producing countries have. Existing literature on local content has not yet identified common factors across countries that influence the achievement of positive local content outcomes. This paper aims at analysing common factors that have led to successful local content outcomes in the countries of Mexico, Brazil, Angola and Nigeria. This exercise is relevant for identifying policy lessons that can be transferred from one country to another. In that sense, this paper addresses the following question: Why have some countries been more successful than others in implementing local content policies? To answer this question the paper attempts to identify relevant common factors by comparing the experiences of Latin American and African oil and gas producing countries that have achieved successful local content outcomes. This analysis is centred around a hypothesis that run as follows: The more a country adopts a specific local content framework focused on the development of its national industry, the more likely it will achieve positive local content outcomes.

2. II.

3. Literature On Local Content

Resource rich countries establish productive development policies (PDPs) (or industrial policies) to strengthen the productive structure of their national economy. These national policies include measures to promote employment or local procurement in the oil and gas industry. Some countries have embraced a comprehensive local content strategy for their oil and gas sectors such as the development of specific frameworks, special capacity building programmes and the creation of implementation and monitoring bodies, amongst others. Commonly known cases include countries such as Nigeria, Ghana, Angola, Mexico, Brazil, Trinidad and Tobago, Indonesia, Malaysia and Norway. Africa is the region where most countries are currently adopting or implementing local content policies. In Latin America, on the other hand, only Mexico and Brazil have adopted specific local content policies. These new developments are driven by a theoretical perspective which calls for open competitive markets but with more distinct roles defined for the private sector and for the government. Under this view, it is argued that private enterprise and capitalist economic development require capable, not passive governmentgovernment that can 'fashion' a sanctuary within which the profit motive and price mechanism can work; that the state has both an enabling role as in the provision of infrastructure, restraining or protective role as in curbing the excesses of private sector in such matters as pollution, in product safety, and a regulatory role as in prevention of unfair banking practices, anti-monopoly laws, and government-established quality standards (Bibangambah, 2001:7). This is what has driven countries to establish local content frameworks and strong institutions such as NOCs and enterprise centres to implement local content strategy.

4. a) What We Know

There are several factors that can influence the successful achievement of local content outcomes. Oil and gas countries have unique contexts that influence the design and implementation of local content policies. First, there are factors related to the preconditions of the countries' oil and gas sectors. These factors can be categorised into four groups: resource conditions, industrial capacity, sector governance and international trade agreements. Geology and geography -or resource endowment -is the first factor that policy makers should consider when designing a local content policy (Tordo et al. 2013). Resource conditions such as the quality of the resource and the location of the reserves are important since they can contribute to defining the industrial capacity, workforce and technology required for the development of the project. Moreover, countries with important and good quality resource endowments have "bargaining leverage" over companies with which they can implement more stringent local content requirements.

Industrial capacity is another important factor when designing local content policies. The level of technology and the industrial base of a country shape the type of local content policy required. If a country's local content strategy is focused on the promotion of local procurement, for example, national and local service companies must count with high levels of technology and the country's national industries must be able to meet international standards required by companies (Heum et al. 2011). If the local content policy aims to develop linkages and spill over effects with the wider economy, the industrial base and technology of the country are essential (Klueh et al. 2007 Counting with resource preconditions and industrial Institutional is not enough when there is lack of governance. Institutional and legal arrangements also matter when designing and implementing local content policy (Tordo et al. 2013). Corruption, lack of transparency and bureaucracy are also challenges that countries and companies commonly face which negatively influence local content implementation (Tordo et al. 2013).

Finally, legally binding agreements that countries subscribe to a common factor that influences the adoption of local content policies. As part of their commercial policy, most countries sign trade agreements with their neighbours or as part of regional trading blocs. Better known as trade-related investment measures (TRIMs), these agreements can limit the capacity of government to enforce the implementation of local content policies (Ado, 2013).

Besides these factors that are related to the sectors' preconditions there are other specific factors that have accounted for the achievement of local content outcomes in oil and gas producing countries. Morales et al. (2016) stressed the importance of welldesigned local content frameworks, strong NOCs and a business-friendly environment when achieving local content outcomes for oil and gas producing countries in Latin America. Kazzazi and Behrouz (2012) supported this conclusion based on a model that identified the correlation between the factors that might influence the development of local content. Their analysis shows a positive correlation (the highest among the variables of their study) between local content policies and local content development (Kazzazi & Nouri, 2012). Similarly, Mushemeza and Okiira (2016) argue that well-designed local content frameworks, the presence of International Financing Institutions (IFIs) such as the World Bank, and the presence of local content implementation and monitoring entities -such as enterprise centres and monitoring boards -are important factors that shape local content outcomes in Africa, especially in Angola, Chad and Nigeria.

Some literature focuses on countries that have achieved mostly positive outcomes and that have developed local content policies to expand their oil and gas sector internationally. For example, in reviewing the case of Norway and the path it took to implement local content policies, Heum (2008) highlights the uniqueness of this case since Norway had strong institutions and an industrialised economy before oil and gas was discovered. These factors enabled Norway to focus on the participation of its national industry within the oil and gas sector first nationally and then internationally. Easo and Wallace (2014) identify as another key factor for Norway (and also for the United Kingdom) its highly educated workforce with technical competence in manufacturing, shipbuilding and engineering. Notwithstanding, the Norwegian and British cases offer few lessons for countries that do not share these characteristics, as is the case for Africa and Latin America.

5. b) What we do not know

A considerable amount of literature is available on specific cases of local content policies adopted by countries. General lessons from benchmark cases such as Norway, the UK, Canada and Malaysia exist but may not apply to countries with entirely different contexts, such as those in Africa and Latin America, resource rich countries characterized by poor governance, corruption, a weak industrial base and workforce.

While African countries have been actively discussing the adoption of local content policies during recent years, Latin American countries have adopted different strategies to promote local content as part of their productive policies, although they have not developed specific frameworks for the oil and gas sector. In many Latin American countries, the policy seems to be to let private companies decide how far they source locally as part of their own efforts to secure and sustain social license or as part of their international mandates. Both Latin American and African oil and gas producing countries have been involved in this dynamic for years and have achieved different kinds of outcomes.

There is a clear gap in existing literature. First, there is lack of analysis of local content outcomes; most of literature focuses the analysis on the type of policies adopted by countries rather than on the achieved outcomes (lack of measurable outcomes). On the other hand, literature is focused on specific cases of benchmark countries rather than on common factors and transferable lessons that account for successful local content outcomes. Our paper represents an initial attempt to fill this gap and provide lessons that can be transferred between countries and regions. Through analysing common factors that have led to successful local content outcomes in Mexico, Brazil, Angola and Nigeria our analysis sheds light on important considerations, for those countries where governments are starting to shape their national oil and gas policies and legislations.

6. III.

7. Comparative Research Methodology

To identify the factors that determine successful local content outcomes in Africa and Latin America, this paper used a comparative framework that considers the experience of seven countries in each region. For this analysis, we selected the countries in Latin America that are the largest oil and gas producers in the region, namely Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico and Venezuela. On the other hand, in Africa we selected sub-Saharan countries that are either oil and gas producers or have significant reserves in relation to their economies. These countries are Angola, Chad, Equatorial Guinea, Ghana, Nigeria, Tanzania and Uganda.

By comparing countries with such different backgrounds and conditions we identified trends amongst the factors that contribute towards achieving positive local content outcomes. The logic behind this comparison is that if we manage to identify factors that are present in every country despite their inherent differences, then, we can identify some of the factors that can help explain the achievement of positive local content outcomes beyond regional or country peculiarities.

Local content outcomes were understood in terms of local employment generation, national industry participation along the oil and gas value chain and skills development for local employees in the oil and gas sector. Thus, we rated each country based on a standardised scoring mechanism that allowed us to make comparisons across countries where local content indicators are not always available or are measured in different ways. Following that methodology, we rated each country's frameworks in one side and their outcomes in other.

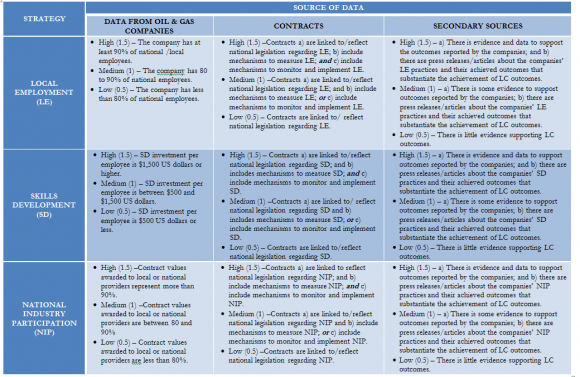

As indicated in Annex 1, we scored the outcomes through the assessment of three broad local content strategies: generation of local employment (LE), skills development (SD) and national industry participation (NIP). Each strategy was scored on a scale ranging from 0.5 (low) through 1 (medium) to 1.5 (high). A score of 0 was given where outcomes could not be identified.

We used three different sources of information to score each strategy -data from oil and gas companies, contracts and secondary sourcesconsidering that data to measure local content outcomes is scattered and often not centralised in one official source. The information used was obtained from public and private oil and gas companies since data to measure local content outcomes at the national level or gathered by a central authority were inexistent in most cases. On the other hand, we used contracts as a proxy to measure outcomes based on the assumption that when local content provisions are included in contracts it means that somehow local content policies have made their way into binding tools that can help to enforce policy into practice and outcomes. Secondary sources include reports and data available in open source formats such as news and media articles or academic publications on local content.

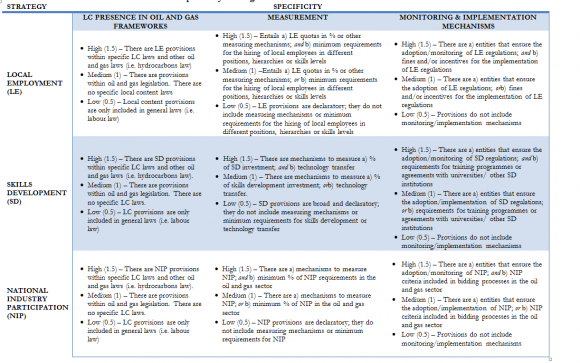

Using that information and based on criteria set out in Annex 1, local content outcomes were scored in all 14 countries, and the two countries with the highest outcomes in each region were selected. This exercise was conducted by both research teams (Grupo FARO in Ecuador and ACODE in Uganda) with inputs by experts from both countries. The results of this process are presented in Table 1 Following the logic of the exercise described above, for the second stage of the analysis we rated each country´s framework. To do so, we assessed each country by using the presence of local content within oil and gas frameworks and the existence of measuring, monitoring and implementation mechanisms within these frameworks. For the purposes of this paper, we refer to these two criteria as specificity (how entrenched local content provisions are in policies and legal frameworks). Annex 2 contains the detailed criteria used to evaluate local content framework's specificity. Each country was ranked on a scale ranging from 0.5 (low) to 1.5 (high). The specificity scores achieved by each country are presented in Table 2 below. In order to draw connections, we compared the LC specificity score with the LC outcomes scores in each country (table 3). Based on this assessment, we found that the countries with higher local content outcomes were also countries where local content policies are well developed and structured. In all four countries with higher local content outcomes, requirements to promote local content are integrated into different strategies (employment generation, national industrial participation, and skills development etc.) and frameworks.

This analysis shows that there is a relationship between the local content specificity scores and the achieved outcomes in these countries. This is particularly clear in the cases of Brazil and Mexico (high LC specificity scores and high outcomes scores) and Argentina, Bolivia and Venezuela (low LC specificity scores and low outcomes scores). This relationship is also present in Angola and Nigeria (high LC specificity score and high local content outcomes) and in Guinea, Tanzania, and Uganda (low LC specificity score and low local content outcomes). This indicates that LC frameworks containing clear objectives and measuring and monitoring mechanisms are more likely to achieve better local content outcomes. Countries that have not achieved high positive local content outcomes, such as Bolivia, Tanzania, Ecuador and Venezuela, are also countries whose LC frameworks are less specific according to our evaluation.

For the second stage of the analysis (next section), we focused on the experiences in Brazil, Mexico, Angola and Nigeria in order to identify the factors that explain the achievement of these positive results. In particular, we analysed which specific institutions, state-led actions and/or policy measures to promote local content were present across the board.

Figure 1 shows the logic of the methodology described above. Thus, In the first stage of our research, we used local content outcomes and frameworks as comparison tools that allowed us to narrow our analysis down from 14 to 4. In the second stage of analysis (next section), we focused on these four case studies to identify the factors that could explain the achievement of positive local content outcomes (see Figure 1). During the assessment of both categories (specificity and outcomes), we also found that the National Oil Companies are actively involved in adopting and implementing local content in countries with higher local content outcomes. In most of countries that presented high positive outcomes, NOCs are used as a mechanism to enforce the provisions contained in legal frameworks mainly through their internal policies (aligned with the frameworks). The seven Latin American have a National Oil Company. Petrobras in Brazil and Pemex in Mexico have played very active roles implementing local content policy in comparison to other NOCs in the region such as Petroamazonas in Ecuador or PDVSA in Venezuela where local content promotion is the responsibility of private companies. The role of these NOCs goes beyond adopting local content laws since Petrobras and Pemex have local content divisions within their corporate structure and have been actively involved in the creation of programmes to develop worker and supplier capacities. In Africa, the cases of Sonangol (Angola) and NNPC (Nigeria) are similar since NOCs are a fundamental instrument through which the government puts local content strategies into practice.

8. IV.

9. Comparative Evidence

Our previous finding was that well-structured local content frameworks and an active role by the NOCs when implementing local content policies can influence the achievement of positive outcomes. To support that, we crosschecked the results against the remaining 10 analysed cases to confirm that those factors were not present in the cases that registered low positive outcomes.

X â??" X â??" â??" â??" â??" Mexico â??" â??" â??" â??" â??" â??" â??" Angola â??" â??" â??" â??" â??" â??" â??" Nigeria â??" â??" â??" â??" â??" â??" â??" Ecuador â??" â??" X X X X X Argentina â??" X X X X X X Bolivia â??" â??" X X X X X Venezuela â??" X X X X X X Colombia X X â??" â??" X â??" X Chad â??" â??" â??" â??" X X X Ghana â??" â??" â??" â??" X â??" â??" Tanzania â??" X â??" X X X X Uganda â??" â??" â??" â??" X X X Eq. Guinea â??" â??" â??" â??" X X XSource: Columbia Centre on Sustainable Investment 2015, authors' own elaboration.

As the table shows our four case studies are indeed the countries with the best-structured frameworks around local content but more important, present at the same time monitoring and implementation mechanisms and their NOCs play a key role during local content implementation. It is important to highlight that while not all aspects of local content were present in every case -for example, in Brazil employment or training requirements are not included in national local content policy or appear only at a basic level -the existence of monitoring and implementation mechanisms proved to be relevant for the achievement of positive local content outcomes in all four countries. In contrast, these mechanisms are non-existent in the other 10 countries.

The existence of well-structured LC frameworks and NOCs involved in the local content implementation process are factors present in countries that have achieved higher positive local content outcomes. Here we analyse the extent to which these factors have contributed to the achievement of positive local content outcomes in Brazil, Mexico, Angola and Nigeria better than other cases in both continents.

10. a) Approaches to Local Content Frameworks

The analysis shows that the achievement of positive local content outcomes has a direct relation with the type of frameworks that oil and gas producing countries from Africa and Latin America have developed to promote local content. Morales et al. (2016) and Mushemeza and Okiira (2016) explore in detail the main provisions of local content frameworks in both regions and their achieved outcomes.

As shown in Table 4, Brazil, Mexico, Angola, Nigeria and Ghana are the only cases among the 14 countries that include within their LC frameworks monitoring and enforcing mechanisms, government programmes to support oil and gas companies in their local content-related activities and the participation of NOCs in local content implementation. These aspects could contribute to explain the positive outcomes these five countries have achieved 4 Regarding institutions, Brazil, Angola and Mexico have designated the tasks of designing and monitoring local content implementation to different state entities such as the National Energy Policy Council (Conselho Nacional de Politica Energética or CNPE) and the National Petroleum Agency (Agencia do ANP) in Brazil, the Ministry of Finance in Mexico and the Ministry of Petroleum in Angola. Similarly, Nigeria has established the Nigerian Content Monitoring Board to guide, implement and monitor the . In order to deepen the analysis, local content frameworks of the four case studies were studied to assess the approach each country has taken to understand the legal, institutional and operational steps these countries have taken, as well as to identify similarities and differences.

The LC frameworks in Brazil, Nigeria and Mexico contain a clear definition of local content unlike Angola. For the case of Brazil, it is interesting to observe that the definition and the main frameworks only focus on the promotion of the country's national industries through procurement practices and bidding processes as opposed to Mexico, Angola and Nigeria, who give importance to employment and skills development as well. Mexico and Nigeria understand local content from a broader perspective, which includes local employment and training for nationals. Despite varying definitions and emphasis on distinct elements of local content, one common denominator among the four countries is the inclusion of clear LC provisions in legislation and contracts, which we treat as specificity in our analysis. The implication of this finding which is in tandem with our hypothesis is that the more specific LC provisions a country has, the more likely it will achieve positive local content outcomes.

The specificity of local content frameworks also includes efforts to measure and monitor implementation. Mexico demonstrates the most concerted effort in this regard, having developed a methodology that has set the ground for monitoring local content compliance among relevant authorities. Brazil also includes the measurement of local content during the bidding process where providers' offers must include local content targets. Brazil and Mexico have created frameworks that prioritise the development of their national industries and have implemented programmes to achieve it. This might explain why more quantitative data is available for Brazil and Mexico on LC outcomes (Morales et.al. 2016) than Angola and Nigeria whose results are scattered across several documents (Nordas et al. 2003;Mushemeza and Okiira 2016).

provisions of the Nigerian Content Act. These institutional mechanisms have proven to play a fundamental role in the implementation of local content development in our selected case studies.

The implementation of LC frameworks has enabled the selected countries (Brazil, Mexico, Angola, and Nigeria) to establish national industry bases with varied strengths and results. Angola focuses on employment and therefore, its frameworks are focused on the establishment of quotas, procedures and penalties to promote jobs for nationals in the oil and gas sector; known as the "Angolanization" of the workforce. In Brazil, provisions relating to national workforce, goods and services are observable. When these frameworks are scrutinised further, the tendency to prioritise national industry participation compared to employment creation is observable. Brazil and Mexico have established mechanisms such as local content minimum requirements for bidding processes and capacity building programmes for suppliers. For their part, Angola and Nigeria prioritise employment by setting employment quotas that are easily adoptable in the short-term. Where local content policies are more focused on the procurement of goods and services (national industry participation) and skills development, countries have managed to develop their manufacturing sector and reduce dependence on oil revenues. Countries in Latin America such as Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela and Bolivia have scattered provision within their oil and gas frameworks. Hydrocarbon Laws and other main frameworks from these countries are focused on fiscal terms instead of local content. Evidence of this investigation has showed that the development of wellstructured frameworks adopted by the four case studies to promote local content have definitely forced the creation of institutions and additional mechanisms to promote and monitor the compliance of local content unlike other countries such as Ecuador, Bolivia, Venezuela, Equatorial Guinea, Chad or Colombia where this process has been slower resulting in less positive outcomes (or none).

11. b) The Role of National Oil Companies in Supporting the Achievement of Positive Local Content Outcomes

National Oil Companies control over 90% of the world's oil and gas reserves and 75% of production. Approximately 60% of the world's undiscovered reserves are in countries where NOCs have privileged access to these reserves and to major oil and gas infrastructure systems. For this reason, it is fair to say that NOCs have the potential to shape the economy and the energy needs of resource-rich countries (Tordo, 2011).

In Latin America and Africa, the creation of NOCs followed different interests and logics. In Mexico, Pemex was established as a mechanism to improve labour and wage conditions for workers whereas in Brazil Petrobras was created to promote self-sufficiency, respond to growing industrialisation and increase the participation of national companies along the oil and gas value chain. NOCs in Nigeria and Angola, as in many other countries in Africa, were during post-independence periods as a mechanism to nationalize assets, regain state control, gain higher rents from foreign companies, generate employment and promote technology transfer (Lwanda 2011;Nwokeji 2007). The experiences of Brazil, Mexico, Nigeria and Angola show that NOCs positively influence the adoption of local content. Unlike other NOCs in Latin America, like PDVSA in Venezuela or YPFB in Bolivia, Pemex and Petrobras follow clear institutional guidelines pertaining to local content that are embedded within the companies' strategies. In addition to existing local content laws, Pemex's work regarding local content is also guided by its Strategy for the Development of Local Contractors and National Content (Pemex, 2013) which recognises the NOC's role as a productive state company in charge of the development of the national industry along the oil and gas value chain.

Petrobras also has an institutional local content policy which indicates that all projects and acquisitions for Petrobras must support the company's strategic plan and maximise local content through the integration of the supply chain (by executing procurement in a coordinated manner), capacity development of local suppliers and supporting local market development to overcome technology gaps. The NOC's LC policy also determines the business areas that are considered a priority for the oil and gas sector and where local content goals need to be achieved. Despite their countries have some legal provisions on local content, neither Petroamazonas (Ecuador) nor YPFB and PDVSA have established local content divisions within the companies or have developed strategies to promote local content.

On the other hand, NOCs in Angola and Nigeria show a similar trend than Pemex and Petrobras whereby the NOC has very well defined guidelines and responsibilities regarding local content. The national LC frameworks clearly position the NOCs as key actors in the implementation process. Sonangol is considered the "national engine" for local content related growth and for the implementation of Angolanization policies intended to increase workforce participation and technology transfer in the oil and gas sector. Within Sonangol, the Local Content Department oversees the developing a local content strategy for the NOC in coordination with the Ministry of Petroleum.

NNPC in Nigeria works under a similar framework as Sonangol. The NOC does not have an internal local content strategy, but it does have a Nigerian Content Division (NCD) that comprises three departments in charge of capacity building, planning and monitoring. These departments identify best practices and advise NNPC on the adoption of local content measures, generate data related to the industry and develop strategies for capacity building.

Another aspect that Pemex, Petrobras, Sonangol and NNPC have in common is the existence of programmes specifically created to translate local content guidelines into practice. In countries like Ghana and Ecuador, where NOCs are relatively strong, there is not the same type of involvement by the NOCs in the local content strategy as in the analysed cases. In Ghana and Ecuador, NOCs adopt local content but are not necessarily seen as key partners when it comes to creating the conditions required for the successful adoption of LC strategies.

Pemex leads the Supplier Relations Programme, which aims to ensure that local suppliers have the necessary capacities to become Pemex suppliers. This programme is based on the idea of collaboration between the NOC and key suppliers at different stages of the value chain. As part of this programme, Pemex has for example developed several initiatives that include an online platform for registering and evaluating suppliers. The purpose behind this platform is to connect supply and demand across different operating areas. As a result of these initiatives Pemex has enabled the country to register positive local content outcomes (Pemex, 2013).

Petrobras has the longest trajectory interacting with suppliers and collaborating with various actors in Brazil to achieve and enhance the adoption of local content. For example, the National Programme for the Mobilisation of the National Oil and Gas Industry (PROMINP), seeks to increase the participation of Brazilian industry in the implementation of extractive projects. Petrobras and the Ministry of Mines and Energy coordinate this initiative. The NOC in Brazil is credited for promoting positive local content outcomes (Petrobras, 2015).

Sonangol in Angola leads various initiatives aimed at strengthening the capacity of local enterprises, establishing factories and technology transfer. Many of these initiatives are public-private partnerships (PPPs) aimed at resolving the challenges that hinder the participation of national industries along the oil and gas value chain such as inadequate infrastructure and engineering equipment, insufficient financial resources to drive change, low technical expertise and limited collaboration between companies. Sonangol participated in the formation of the Angolan Enterprise Program (AEP) designed to develop the capacities of SMEs with the support of IOCs such as Chevron. The Nigeria National Petroleum Company (NNPC) implements its local content strategy through the National Petroleum Investment Management Services (NAPIMS). NAPIMS oversees the monitoring the contracting procedures of NNPC ensuring that local content criteria are present in every contracting process. NAPIMS also provides capacity building for suppliers to ensure their ability to participate in the bidding processes of the industry. Within NNPC, the National Content Division is in charge of developing projects to bridge local capacity gaps in the industry, as well as certify and train local providers by partnering with IOCs through PPPs. The spirit of PPPs promoted by the government and the NOC gave birth to the Enterprise Development Centre (EDC) hosted by the Pan African University since 1991. In terms of local content outcomes, the EDC trained 46 trainers, including 16 women, to deliver Business Edge workshops to 1,367 individuals including 414 women. At least 24,000 entrepreneurs and small business owners submitted business plans to the first You WIN Competition and 1,200 won between $7,000 and $70,000 US dollars in seed funding to start or expand their business (Mushemeza and Okiira 2016).

Despite the lack of a strong and independent measurement and evaluation system, the NNPC is credited for spearheading several developments and local content outcomes. The Nigerian Content Development Monitoring Board estimates that local capture of oil industry spends have risen from 5 to 40% in the last decade. It is estimated that with an annual investment of $15 billion US dollars per year, local content practices could help retain over $5 billion US dollars in the Nigerian economy annually (Ovadia, 2014). Nigeria's Ministry of Petroleum Resources estimates that in 2012 implementation of the Local Content Act led to retention in the national economy of over $20 billion US dollars. Between 2010 and 2014, NNPC trained and employed 15,000 personnel representing 80% of local employees in the sector. In the same period, the NOC awarded contracts to national and local companies at a value of $52 billion US dollars -a clear success for national industry participation (Mushemeza and Okiira 2016).

It is important to highlight that, the fact that these NOCs have a fundamental role in the achievement of positive local content outcomes, does not mean that their activities are managed with transparency. Moreover, Petrobras and Sonangol have been recently involved in corruption scandals that reached international levels.

V.

12. Policy Implications

The analysis leads to at least three key lessons. Unlike other oil and gas producing countries from Africa and Latin America, Angola, Nigeria, Brazil and Mexico have achieved positive local content outcomes due to these countries have structured their frameworks with specific provisions that addresses issues on technology, procurement, employment and training requirements, complemented by the establishment of monitoring and enforcement mechanisms, government support for oil and gas company programmes and the active participation of NOCs during local content implementation. Based on the evidence of Brazil, Mexico, Angola and Nigeria, it can be concluded that oil and gas producing countries that are in the process of designing local content o policies should pay attention to the development and structure of specific local content frameworks to achieve positive outcomes. These frameworks should be accompanied by monitoring and enforcing mechanisms as the ones assessed during these research (table 3).

While presence of NOCs can foster employment and technology transfer, it is not enough. Other factors can influence the extent to which existence of the NOC can lead to positive outcomes. These include the extent to which the NOC collaborates with private sector and international oil companies to enhance knowledge and technology transfer. For example, NNPC and Pemex adopted measures to promote the participation and competition of private companies and partners. The experiences of Petrobras and Sonangol highlight the importance that knowledge transfer can have for the development of strong technological basis in an oil company. These results show that openness to the participation of private stakeholders does not diminish the NOCs' influence; on the contrary it strengthens its capacity and performance. NOCs should play a prominent role when defining and implementing local content. Their involvement in this process can lead to positive local content outcomes despite other structural challenges such as limited independence from the government. The cases of Sonangol, NNPC, Petrobras and Pemex show that it is important that NOCs' policies are connected with local content frameworks. Thus, NOCs have legally binding obligations to adopt local content as part of their strategy and therefore are more likely to achieve positive local content outcomes. However, these case studies also highlight the importance of strengthening the institutional capacities of the extractive sectors in resource rich countries. transparency that has also been found in all the analysed countries as part of this study.

13. VI.

14. Conclusion

This paper started by comparing local content in 14 oil and gas producing countries across Africa and Latin America in order to identify their local content frameworks and the outcomes these countries have achieved. Through this comparison, it was possible to identify the countries with better local content outcomes in both regions, namely Mexico and Brazil in Latin America and Angola and Nigeria in Africa.

The comparative analysis shows that these four countries demonstrate several common features. On the one hand, the existence of sound local content frameworks that are well structured and positioned within the country's legislation, and which include clear implementation and monitoring mechanisms. On the other hand, National Oil Companies in these countries have played an important role during the design and implementation of local content policies. Unlike other NOC elsewhere, national oil companies in Brazil, Mexico, Angola and Nigeria are not only in charge of adopting local content, they are also involved in the policy design process and are the institutions in charge of promoting its adoption, and even measuring and monitoring its implementation.

Angola, Nigeria, Brazil and Mexico have achieved positive local content outcomes unlike other oil and gas producing countries from Africa and Latin America. These countries have structured their frameworks with broad provisions and with specific technology, procurement, employment and training requirements, complemented by the establishment of monitoring and enforcement mechanisms, government support for oil and gas company programmes and the active participation of NOCs during implementation. Evidence suggests that having a specific local content framework and a strong NOC with clear guidelines and strategy, can lead a country to achieve positive local content outcomes regardless of context. While presence of NOCs can foster the generation of employment and technology transfer, it is important to keep in mind that the mere existence of NOCs is not enough. There are specific dynamics and factors inside the management of a NOC that can shape local content. For example, it is valuable for a NOC to collaborate with the private sector and international partners to enhance knowledge and technology transfer. NNPC and Pemex adopted measures to promote the participation and competition of private companies and partners. The case studies show that openness to the participation of private stakeholders does not diminish the NOCs' influence; on the contrary it strengthens their capacity and performance. The experiences of Petrobras and Sonangol highlight the importance that knowledge transfer can have for the development of strong technological basis in an oil company. NOCs should play a prominent role when defining and implementing local content. Their involvement in this process can lead to positive local content outcomes despite other structural challenges such as limited independence from the government. However, these case studies also highlight the importance of strengthening the institutional capacities of the extractive sectors in resource rich countries.

Policy makers should consider short and longterm benefits when designing local content policies. The achievement of short-term positive outcomes might be easier to attain through certain mechanisms such as the establishment of workforce and procurement quotas and scholarships requirements. However, building linkages through local content policies is a measure that can bring about longer-term benefits to the country's economy. As analysed, Angola and Nigeria have focused their local content policies on the generation of jobs and this has not contributed to a decrease in either country's dependence on oil revenues. On the other hand, Mexico and Brazil have established local content policies more focused on the procurement of national goods and services and have thereby managed to develop their manufacturing sector and reduce dependence on oil revenues.

The factors analysed in this paper do not rule out or ignore the existence of other factors that can shape the positive achievement of local content outcomes such as the size and quality of a country´s natural endowments, the existing industrial capacity or the quality of governance institutions.

| Region | Country | LC Outcome Score (average) | |

| BRAZIL | 1.10 | ||

| MEXICO | 1.05 | ||

| COLOMBIA | 1.00 | ||

| Latin America | ECUADOR | 0.72 | |

| BOLIVIA | 0.50 | ||

| VENEZUELA | 0.44 | ||

| 1 | |||

| ARGENTINA | -- | ||

| ANGOLA | 1.08 | ||

| NIGERIA | 1.08 | ||

| CHAD | 0.95 | ||

| Africa | GHANA | 2 | -- |

| GUINEA | 0.67 | ||

| TANZANIA | 0.50 | ||

| UGANDA | 0.50 | ||

| Region | Country | LC Frameworks Scores |

| BRA | 0.94 | |

| MEX | 0.89 | |

| COL | 0.78 | |

| Latin | ||

| ECU | 0.78 | |

| America | ||

| BOL | 0.61 | |

| VEN | 0.61 | |

| ARG 3 | 0.44 | |

| ANG | 1.16 | |

| NIG | 0.89 | |

| CHA | 0.67 | |

| Africa | GHA | 0.89 |

| GUI | 0.67 | |

| TAN | 0.50 | |

| UGA | 0.50 |

| Region | Country LC Frameworks Scores | LC Outcomes Score | |

| BRA | 0.94 | 1.10 | |

| MEX | 0.89 | 1.05 | |

| COL | 0.78 | 1.00 | |

| Latin | |||

| America | ECU | 0.78 | 0.72 |

| BOL | 0.61 | 0.50 | |

| VEN | 0.61 | 0.44 | |

| ARG | 0.44 | -- | |

| ANG | 1.16 | 1.08 | |

| NIG | 0.89 | 1.08 | |

| CHA | 0.67 | 0.95 | |

| Africa | GHA | 0.89 | -- |

| GUI | 0.67 | 0.67 | |

| TAN | 0.50 | 0.50 | |

| UGA | 0.50 | 0.50 | |

| Stage 1 | Stage 2 | ||||

| Analysed | Analysed | ||||

| Aspects of Comparison | Aspects of Comparison | ||||

| Countries | Countries | ||||

| 14 countries | 4 countries | ||||

| ? | 7 Africa | Local content outcomes | ? | 2 Africa | Factors that lead to positive local content outcomes |

| ? | 7 Latin America | ? | 2 Latin America | ||

| Year 2017 | |||||

| 51 | |||||

| Volume XVII Issue III Version I | |||||

| E ) | |||||

| ( | |||||

| Global Journal of Human Social Science - | |||||

| below presents the | |||

| information gathered from each country on the existence | |||

| of local content requirements for employment, national | |||

| industry participation, training and technology transfer; | |||

| monitoring | and | implementation | mechanisms; |

| government programmes to support oil and gas | |||

| companies in their local content-related activities; and | |||

| NOCs participation in local content strategies and | |||

| programmes for all 14 countries. | |||

| Employment Requir. | NIP Requir. | Training Requir. | Tech. Transfer Requir. | Monitoring and Implementation Mechanisms | Government supports oil & companies gas | NOCs participation |

| Brazil |

| Year 2017 |

| 55 |

| Volume XVII Issue III Version I |

| E ) |

| ( |

| Global Journal of Human Social Science - |

| Year 2017 |

| 56 |

| Volume XVII Issue III Version I |

| E ) |

| ( |

| Global Journal of Human Social Science - |