1. Introduction

t is no longer a secret-if, indeed, it ever was-that escalating textbook costs are putting them beyond the affordability of many students. Senack (2014) in a survey of 2,039 university students, reported that 65% of students had no other choice than opting out of buying a textbook due to expense, and of those students, 94% admitted that doing so would negatively affect their grade in that course. These findings are representative of several other studies (see, for example, Acker, 2011; N. Allen, 2011; Florida Virtual Campus, 2012; Graydon, Urbach-Buholz, & Kohen, 2011; Morris-Babb & Henderson, 2012; Prasad & Usagawa, 2014), showing that affordability of traditional textbooks has become more difficult for many students and thus, in some cases, a barrier to learning.

Despite the problems outlined above, there is no indication that textbook prices will decrease in the foreseeable future; on the contrary, trends point to further increases. However, fortunately, open textbooks hold promise to provide a solution. Weller (2014) appraises open textbooks, a type of open educational resource, as one most amenable to the concept of open education, a concept essentially about elimination of barriers to learning (Bates, 2015). The phrase open educational resource (OER) is an umbrella term used to collectively describe those teaching, learning, or research materials that can be used without charge to support access to knowledge (Hewlett, 2013a). Within the OER context, "freely" means both that the material is openly available to anyone free of charge, either in the public domain or released with an open license such as a Creative Commons license; and that is made available with implicit permission, allowing anyone to retain, reuse, revise, remix, and redistribute the resource (Center for Education Attainment and Innovation, 2015). Conversely, traditional textbooks are extremely expensive and are published under an All Rights Reserved model that restricts their use (Wiley, 2015).

Within the past few years a growing body of literature has examined the potential cost savings and learning impacts of open textbooks. Senack (2014), for example, in a survey of 2,039 university students indicated that open textbooks could save students an average of $100 per course. Similarly, Wiley, Hilton, Ellington, and Hall (2012) in a study of open textbook adoption in three high school science courses found that open textbooks cost over 50% less than traditional textbooks and that there were no apparent differences (neither increase nor decrease) in test scores of students who used open versus traditional textbooks, a finding replicated by Allen, Guzman-Alvarez, Molinaro, and Larsen (2015). This latter finding is in contrast with the findings of Hilton and Laman (2012), who reported that students who used open textbooks instead of traditional textbooks scored better on final examinations, achieved better grades in their courses, and had higher retention rates. A study by Robinson, Fischer, Wiley, and Hilton (2014) (Hewlett, 2013b). The amount of money injected into such projects is significant, and therefore funders, besides requiring usual information about impacts on cost and learning outcomes, are now also increasingly asking for more rigorous information regarding ways-whether, when, how often, and to what degree-in which learners actually engage with their open textbooks. More specifically, as stressed by Stacey (2013) The above discussion points to the need for more sophisticated methods of monitoring open textbook utilization in order to meet these information needs. New analytical methodologies-particularly learning analytics-have made fulfilling this requirement possible. Compared with more subjective research methods such as surveys and questionnaires, learning analytics can capture learners' authentic interactions with their open textbooks in real time. This may improve understanding of textbook usage influences on actual usage behavior, which in turn may help improve efficiency and effectiveness of open textbooks. The method can be used either as a standalone method or to support other traditional research methods. Moreover, learning analytics for open textbooks can provide new insights into important questions such as how to assess learning outcomes based on textbook impact; whether student behavior, content composition, and learning design principles produce intended learning outcomes; and the level of association between amount of markups done and the relevance and difficulty level of the book content areas.

Despite these great potential benefits, so far there exist no studies published to date on systems developed for open textbooks learning analytics. Thus, the main aim of this paper is to close this gap by presenting developmental work and functionalities of a conceptual open textbooks learning analytics system. A distinctive feature of this proposed system is its ability to synchronize online and offline interactional data on a central database, allowing both instructors and designers to generate analysis in dashboard-style displays.

The remainder of this paper is organized in the following manner. It starts with a brief review of literature related to learning analytics, followed by a summary of the framework that guided our development. Next, it describes techniques and tools applied in development of the conceptual learning analytics system for open textbooks, which is the main focus of this paper. The final section concludes the paper and talks about future work.

2. II. Literature Review on Learning Analytics

The concept of learning analytics has been making headlines for some years now, firing up interest amongst the higher educational community worldwide, but its definition remains unified. One frequently cited definition is "the measurement, collection, analysis and reporting of data about learners and their contexts, for the purposes of understanding and optimizing learning and the environments in which it occurs" (Siemens & Long, 2011, p. 34). In other words, learning analytics applies different analytical methods (e.g., descriptive, inferential, and predictive statistics) to data that students leave as they interact with and within networked technology-enhanced learning environments so as to inform decisions about how to improve student learning. A survey of published research shows that learning analytics tactics have been applied in a variety of ways and found useful, some of which include identifying struggling students in need of academic support (Arnold & Pistilli, 2012 (Fritz, 2013).

Given the benefits and opportunities offered by learning analytics, researchers and practitioners have expressed concern about the importance of maintaining the privacy of student data. As Scheffel, Drachsler, Stoyanov, and Specht (2014) emphasize, the nascent state of learning analytics has rendered "a number of legal, risk and ethical issues that should be taken into account when implementing LA at educational institutions" (p. 128). It is common to hear that such considerations are lagging behind the practice, which indeed is true. As such, many individual researchers, as well as research groups, have proposed ethical and privacy guidelines to guide and direct the practice of learning analytics. In June 2014, the Asilomar Convention for Learning Research in Higher Education outlined the following six principles (based on the 1973 Code of Fair Information Practices and the Belmont Report of 1979) to inform decisions about how to comply with privacy-related matters on the use of digital learning data. 1) respect for the rights and dignity of learners, 2) beneficence, 3) justice, 4) openness, 5) the humanity of learning, and 6) the need for continuous consideration of research ethics in the context of rapidly changing technology. Similarly, Pardo and Siemens (2014) in the same year identified the following four principles: 1) transparency, 2) student control over data, 3) security, and 4) accountability and assessment.

Furthermore, in a literature review of 86 articles (including the preceding two publications) dealing withethical and privacy concepts for learning analytics, Sclater (2014) found that the key principles which their authors aspired to encapsulate were "transparency, clarity, respect, user control, consent, access and accountability" (p. 3).

In this context, it is worth noting that "a unified definition of privacy is elusive" (Pardo& Siemens, 2014, p. 442), just like the definition of learning analytics as noted earlier. While there is no unified definition of learning analytics and its privacy practices, there is general agreement that it is crucial for higher educational institutions to embrace learning analytics strategies as a way to improve student learning, but without violating students' legal and moral rights.

3. III.

4. Conceptual Framework

Developmental work was guided by our earlier work proposed in (Prasad, Totaram, &Usagawa, 2016) describing a framework for development of an open textbooks analytics system, as shown in Figure 1. This framework supports textbooks in the EPUB format, a format that has become the international standard for digital books. EPUB file formats are actually advanced html text pages and image files that are compressed and then use a file extension of .epub. Notably, this framework is not specific to open textbooks but equally applicable to other EPUB digital books.

5. System Development : Techniques and Tools

Based on the suggested framework presented above, this section describes methods applied and technologies used in the development of learning analytics system for open textbooks in EPUB format, and is divided into two subsections: data collection, and data analysis and presentation.

6. IV.

7. Data Collection Data Recording

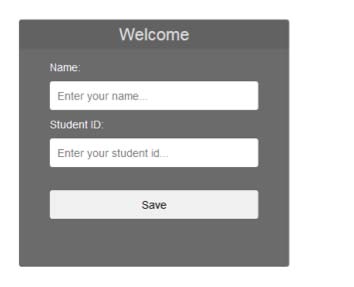

Reading books in EPUB format requires an EPUB reader application. In line with the suggestions of the framework, EPUB.js (https:// github.com/ futurepress /epub.js), an open source web-based EPUB reader application, can be adopted and customized as a central tool to aid datacollection. EPUB.js previously possessed capabilities to record user clicks and annotation data in the local storage of the web browser used by the user to access the EPUB.js application. These capabilities were expanded to record and track a variety of other data, such as user's IP address, web browser type and version, and the type of device used. Following these modifications to the EPUB.js reader application, the EPUB file of the book was embedded into the reader application for standard data collection. Figure 2 represents the customized EPUB.js reader application's user interface. This customized version was used for both online and offline delivery. For online use, the customized EPUB.js reader application was hosted on a web server accessible via the Internet from any web browser. To facilitate offline access, an application installer was created for the Windows platform as the majority of users used Windows-based computers. This installer conveniently installed the customized EPUB.js reader application to the users' computers (Figure 3). However, offline access was limited to a particular web browser: Mozilla Firefox. This is because the customized EPUB reader application used Javascript to send user data to an external data storage server, which most web browsers blocked as a potential security risk. Thus, for offline access, the user interaction recording features were incompatible with most web browsers. Consequently, offline access of the EPUB reader application required the use of Mozilla Firefox (Figure 4). Further development is required to make the code compatible with other web browsers. application is initiated by the user, requiring the user to enter their name and student ID number. These credentials are stored in the local storage of the user'sbrowser, and all user-interaction data sent to the server (and subsequently processed) is tagged with the user's authentication details. The Praxis of Learning Analytics for a Conceptual Open Textbooks System V.

8. Data Synchronization

Data generated during offline usage are stored in the browser's local storage. For the purpose of synchronizing data from web browser's local storage to server, a network-sensing feature was integrated into the EPUB.js reader. This feature checks for an Internet connection at regular intervals (in our case, every 60 seconds) to determine if the user's device is connected to the Internet, and whenever an Internet connection is detected, data from the browser's local storage are sent to the central database server, where the data is used for analytics. However, when used in online mode, the interactional data is directly sent in a database.

9. VI.

10. Data Storage

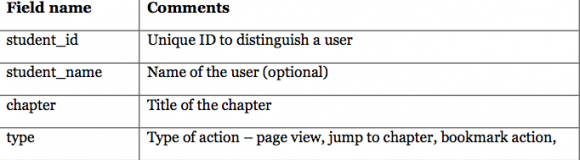

A central database server, a combination of a PHP script and MySQL database, can be used for data storage. The MySQL database is used to store data, while the PHP script waits for the interaction data to be received from the EPUB reader application. Once receiving new interaction data, the PHP script can validate and records it to the MySQL database. Table 1 shows sample data types recorded for each user interaction.

11. Data Analysis and Presentation

Analysis can be performed on both individual and aggregate (whole class) data, and can be analyzed with regard to various factors as listed below.

12. ?

Links clicked per chapter, per student, or for whole class: This is the count of the links clicked in each chapter.

? Popular web browser used by the users to access the ebook: This is the count of each web browser used.

13. ?

Popular type of device used by the users to access the ebook: This is the count of each device type used.

? Online versus offline usage: This is the count of the all user interaction for online access and offline access.

? Number of students versus chapters viewed: This is the count of the number of students who viewed each chapter.

14. ?

Total views per chapter, per student, or for whole class: This is the count of the number of page views for each chapter.

15. ?

Total bookmarks per chapter, per student, or for whole class: This is the count of the number of bookmarks made in each chapter.

16. ?

User annotations/notes made per chapter, per student, or for whole class: This is a list of all the annotations/notes made for each chapter. viewed: This is the count of the number of students and the count of the number of chapters viewed by each student.

17. ?

? Weekly user interaction: This is the count of the number of interactions by all users grouped by weeks.

The analysis and data presentation (graphic visualizations in dashboard format) can be done using PHP and a Javascript charting library. Computation of interaction data can be done using SQL queries, while the rendering (in dashboard display format) can be done using PHP with the help of a Javascript charting library. Figure 6 shows snapshot of the sample learning analytics dashboard.

| these studies have put forth evidence showing that | ||||

| replacing traditional textbooks with open textbooks | ||||

| substantially reduces textbook costs without negatively | ||||

| affecting student learning. Consequently, demand for | ||||

| open textbooks is increasing. | ||||

| As demand has grown, so too have efforts to | ||||

| develop and distribute open textbooks. Many of these | ||||

| development | and | distribution | practices | are |

| accomplished through a combination of government, | ||||

| private, and philanthropic funding | ||||