1.

Abstract-This paper presents a research that was carried out in autumn 2015 about the unconventional political demonstration of secondary education pupils. The sample consisted of 960 questionnaires that were collected from schools of central Macedonia. The purpose of this research was to examine the factors that influence pupils to occupy schools every autumn and to describe the profile of the pupils that act in this way. At first a brief introduction in the notion of political socialization is attempted putting forward the factors that determine the degree of pupils' politicization such as the family, the peer group, the school and the mass media. Secondly, a link between political socialization and political demonstration is attempted commenting on the habit of occupying schools every autumn. The results of the research show that the majority of students do not participate in such actions as well as a tendency of male pupils to participate more than the female. Also, pupils from vocational schools show a tendency to take part in occupations as well as in provocations in relation to pupils from gymnasia and normal high schools (lyceums).

2. I. Introduction

chool is one of the most important socialization entities, because apart from conveying knowledge and developing the skills of students, aims at transmitting values and rules that govern the function of society as a whole. Herbert Hyman, who for the first time referred to the notion of political socialization, described it as "the learning of social patterns, corresponding to (...) social positions as mediated through various agencies of society" (1959: 25). Many scholars have dealt with this notion and the way it is defined, used and evolved in time.

It is obvious that socialization is an important factor of transmitting political interest. Different actors play an important role in this process, in parallel with the mass media (Adoni, 1979? Lupia & Philpot, 2005) and the political climate (Muxel, 2001? Sears & Valentino, 1997). An important parameter of sensitization is that of social networks that comes from the field of sociology. Lazega (1994: 293) describes it as the sum of special type relations (cooperation, advice, control, influence etc.) among the actors. Whereas parents typically are recognized as the primary factor of social network, two others should not be neglected: the peer groups and the teachers. The influence of these three factors is not the same, due to the fact that their role in adolescents' life is different and evolves as time goes by. Parents typically are considered as the most important socialization factor, at least for the adolescents. The first studies in relation with political socialization, which were conducted in 60s and 70s, emphasized the relation between the parents and the youngsters (Dawson & Prewitt, 1969? Dennis, 1973? Jaros, 1973), and referred to the influence of the former to the latter.

As the adolescents grow up, their friends become more important. Berndt reports that the most essential occupation of adolescents is the conversation with their peer groups (Berndt, 1982). From his point of view Coleman mentions that even though adolescents solemnify their parents, pursue at the same time the approval, the admiration and the respect of their friends in their everyday activities in and out school (Coleman, 1961).

Whereas the importance of friends during adolescence has been studied a lot, their influence in political socialization is not obvious and only a bunch of scholars has dealt with it. One of them, Campbell (1980Campbell ( , 2004Campbell ( , 2006)), found a weak influence of peer groups, while Lange (2002) figured that peer group influence is focused on the hardest issue in his opinion which is the transition from the medium to the highest level of political activity. Whereas parents and friends remain emotionally close to adolescents, the teachers also play an important role in the socialization process. The adolescents every day spend at least five hours paying attention to what their teacher say. Some of them may speak about politics, either as a part of an educational program, or because a teacher feels the need to speak about it. These discussions will have a repercussion on the development of adolescents' political interest. Every school has its special characteristics but generally it plays a defining role.

Year 2015

3. ( ) F

The first results regarding the influence of school on political socialization were pretty disappointing. Langton and Jennings figured that civic education as a subject did not have in any way an impact on political socialization. They considered that the link between the number of civic education subjects and variables such as general political knowledge and interest for political discussions is so impossible that persons in charge should seriously think the abolishment of these subjects. Their conclusion is obvious: "Our findings do not support those who believe that curricula of civic education in American high schools are a source of political socialization" (Langton & Jennings, 1968: 863).

Since then this point of view has been confuted and school gains its status as an important factor in the process of political socialization. Many contemporary researches have proved the essential role of civic education as a subject in the development of political conscience (Claes, Stolle & Hooghe, 2007? Denver & Hands, 1990? Niemi & Junn, 1998). Apart from learning procedure, Tournier (1997) reached the conclusion that school and family interact, so as to develop the ideological preferences (left or right) of French students while David Campbell (2006) remind us that the social frame often is not taken into account in the procedure of socialization. Adolescent experiences have an impact on the adult behavior with the civic norms that are learnt in young age having a long term results, especially as the participation is concerned. Despite the fact that school impact shows to regain its power, studies do not reach the same conclusion as the teachers' impact is concerned. In a relevant research it has been deducted that political discussions are not an important part of teachers' role. Even though teachers believe that school is an essential factor of political socialization, they attribute a more important role to family and to mass media for this purpose (Trottier, 1982). Some researchers believe that school is the most crucial entity of socialization because its defined role is the promotion of knowledge (???????? & ????????, 2000). In Greek educational system political learning takes place through teaching subjects such as Civic Education in the third grade of Gymnasium, Civic Education in the first and second grade of Lyceum, Politics and Law in theoretical field of second grade of Lyceum, Basic Principles of Social Sciences in the second grade, Sociology in the third grade of Lyceum and History in all grades of Gymnasium and Lyceum. Additionally political learning is obtained indirectly though ceremonies and national holidays as well as in extracurricular activities like student councils and sports that can promote cooperation and tolerance. The major socializing project of school is located in the framework of knowledge, especially in transmitting knowledge for constitutional principles and for applying them in citizens' occupation with politics. Students who obtain this knowledge feel capable of participating in politics. Possibly they can become more eager to be informed by mass media about issues that concern politics and to be more energetic in local community. Studies revealed that school efficiency in developing civic orientations depends on the abilities of teachers and the innovations of school curricula (Owen, 2008).

Students that have experiences of innovative approaches, such as lesson plans, which are connected directly with political issues, tend to deal more with politics during their adulthood. Even though schools have great abilities as entities of political socialization, they do not always achieve successfully their work and do not teach the basics about government. Moreover, the average time that is spent on issues about civic education is less than three hours per week. A phenomenon that is repeated periodically the last years is the sit-in of the schools due to students' protestations about different aspects of the educational system. This tendency is not accidental but is repeated every academic year especially in autumn. A lot of studies have been written which connect the sits-in as unconventional political demonstration with political socialization of students in school (???????, 2006).

4. II. Political Demonstration by Adolescents

In western democracies there is the prediction by the labor legislation that workers can go on strike aiming at exerting pressure, so as to safeguard their rights against their employers. The right of strike is an ultimate resort and is applied in those cases in which efforts to mutual understanding and compromise between workers and employers fail. The meaning of this right consists in the fact that it realizes the scope for which it was created as long as it is used prudently. To substantiate the last argument the international statistical analyses show that the more a country prosper and its economy indices are high, the less its workers use this right (OECD. 2012).

According to some researchers the phenomenon of sits-in of schools is a kind of strike on behalf of students and it is categorized conceptually in the frame of the so-called youth political demonstration which uses unconventional media of political participation (Barnes & Kaase, 1979). Some ascertainments and findings that were arisen from researches in 60s and 70s regarding university student demonstrations are valid in the case of pupils sits-in in a certain degree, taking of course into account pupils age and their political immaturity.

It has to be noted that pupils' political immaturity is valid respectively and for pupils of other European countries -with differences among the countries. Nevertheless schools sits-in by European pupils are very rare, considering also the periodicity of this institutional anomaly and the damages that it causes, as it happens in Greece (Kim, 2007).

It is a fact that sits-in as a kind of political demonstration on behalf of pupils disorganize school learning procedure, which in every organized society is the way of transmitting knowledge and the normative patterns of its cultural system to the next generation, aiming at the timeless maintenance of society's cultural identity as the generations pass. The cases of civilizations with a weak educational system which did not maintain their cultural identity and disappeared as the centuries were passing by, prove the legitimacy of functionalists' points of view who claimed that educational system is the reproductive system of a society.

According to functionalist theory, versus workers who have strike as their working right, pupils, in the status that they are due to their age, do not provide neither a productive result to the society nor a service whatsoever but, on the opposite, they are recipients of society's benefits. To the adolescents that are in the status of pupil, modern welfare states have provided extra privileges due to institutionalized extension of puberty which takes place in modern states and their sole obligation to the society is their compliance with the rules of school teaching and learning. This benefit on behalf of the society functions primarily as an advantage of their development having as an ultimate aim the improvement of their standard of living (?????????? 2002: 230-236, ?????????? 1991: 109-128). School as the main civic institution of the socialization process focuses on the preparation of youngsters for their future integration to the society.

The most important result of the repetitive tendency of the pupils to access to the medium of sits-in of schools is not the loss of lessons and the damages that happen which are not negligible in any case, but the decline of school as an institution and its prestige, due to the fact that this institution forms the future active citizens in well-organized societies (Î?"??????? 1996: 10). The school in these societies is the place where the respect and the acceptance of civic institutions and normative patterns are internalized by the young members. Consequently, the decline of its prestige as an institution brings forward inevitably the decline of civic institutions' prestige as a whole. It is not possible for the young members of the society to internalize respect and the acceptance of normative patterns within a weak procedure of education by an institution which essentially has no prestige. Because it is self-evident that a school that has lost its institutional prestige, is not in a position to transfuse to its pupils the respect towards other civic institutions and the relevant normative patterns.

5. III. Purpose of the Research

The purpose of this research is to examine secondary education pupils' points of view about political demonstration which is expressed in two ways: either with the sit-in of schools or with the provocative attitude towards the teachers with whom pupils disagree. Also, statistical significant relations will be seeked among these variables and independent ones such as pupils' sex, type of school and the general grade. Additionally, youth political demonstration will be examined in relation with the watching of informational programs on television.

6. IV. Methodology of Research

For the examining of the researching problem survey was considered as the most appropriate method which, despite its limitations, is considered more advantageous for the purpose of participating a large number of secondary education pupils from central Macedonia. Schools from the prefectures of Kilkis and Thessaloniki were chosen so as to be presented the pupils' points of view from urban, semi-urban and rural areas.

The questionnaire of this research was based on two previous researches that were conducted for similar reasons. The first is the research that was conducted by Michalis Kelpanidis in 2012 and concerned the examining of pupils' points of view about sits-in. The second is a research conducted by Staurakakis and Demertzis about the youth and their attitudes on different issues of their daily life (Î?"???????? & ???????????, 2008). At first, a pretest research was conducted in a lyceum class so as to ascertain pupils' attitude towards the questionnaire and to calculate the time that was needed in order for the pupils to fill it. In general the results showed a good reception while time did not exceed 25 minutes. Once the research was approved by Institute of Educational Policy and instructions were given, letters were sent to pupils' parents so as to approve the participation of the pupils to the research. It has to be noted that all parents gave their consent without any objections. After having distributed approximately 1100 questionnaires to pupils, 960 were given back and this is the final sample of this research.

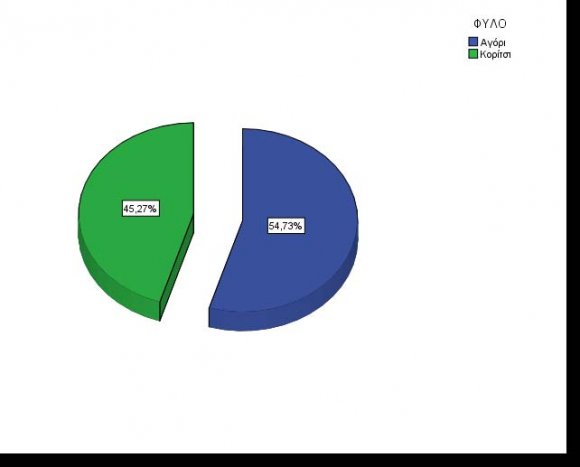

In this research six schools from central Macedonia took part: a general lyceum and a gymnasium of Thessaloniki, a vocational school from the prefecture of Kilkis, two general lyceums and a gymnasium from the prefecture of Kilkis which belong to a semi-urban area because the population of the town is more than 10000 inhabitants and one lyceum and a gymnasium from rural areas, that is villages with less than 2000 inhabitants. The exact number of pupils regarding the area where they live is presented in the following table 1: The sex of the pupils that participated in this research is presented in the following chart and it shows that 54,7% are boys and 45,3% are girls:

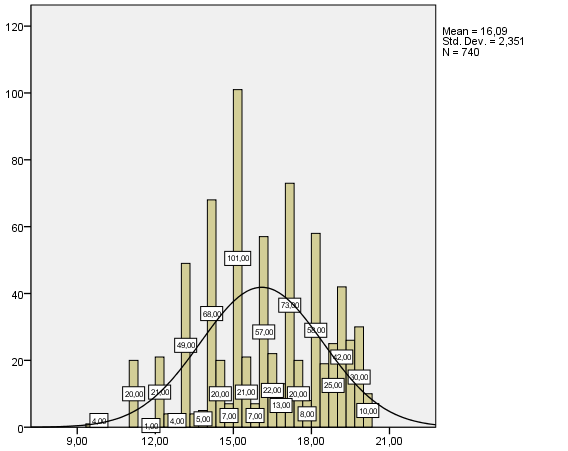

Chart 1 : The sex of the pupils of the research As pupils' ages were concerned, great variance is observed due to the fact that in this research a vocational school took part in which older pupils attend. Also, in the area there is not a second chance school and many adults who did not complete their secondary education, choose the vocational school to acquire the necessary skills. The ages of the pupils are presented in table 2: The performance of each pupil as it is depicted in the final grade will be an important independent variable for further analysis. The following chart shows that the average grade of 740 questionnaires is 16.09 and its standard deviation is 2,351. It has to be noted that 220 pupils did not want to answer claiming that this information is personal data irrelevant with the purpose of this research. Next, some demographic data will be presented, considering them as crucial factors of political socialization. Parents' profession was examined as well as their educational level. Mother's and father's educational status were examined separately. Table 5 presents the frequencies of each case: As the value missing is concerned, it refers to the cases where either father or mother does not work willingly or unwillingly. The percentage of unemployed mothers is 31.7% and of unemployed fathers is 16.7%. As their educational level is concerned, the majority of both parents are graduates of lyceum and a large percentage are holders of universities and technological educational institute degrees. The frequencies of educational level are presented in the following table 6: In order to be examined the reliability of the sample chi-square goodness of fit tests were used.

7. Global Journal of Human Social Science

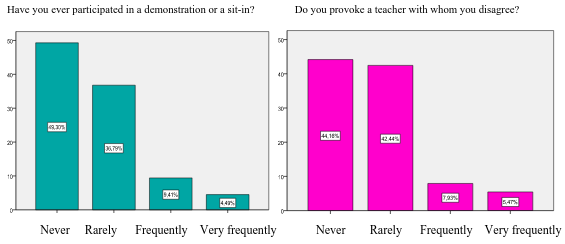

Cluster analysis showed a great level of correlations between the variables that were used. Moreover The index of unconventional political demonstration consists of two variables: the first is related with the participation of the pupils to demonstrations and sits-in of schools and the second with the provocation that a pupil can address to teachers in their everyday interaction. Frequencies that are presented in the following charts show that in general the majority of pupils in both cases are against the demonstration and the provocative behavior. This point contrasts the usual behavior that takes place every year in Greek schools, showing that youth political demonstration that is expressed with unconventional means is realized by minorities.

8. Chart 3 : Variables of youth political demonstration index

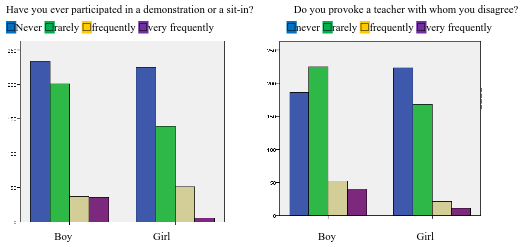

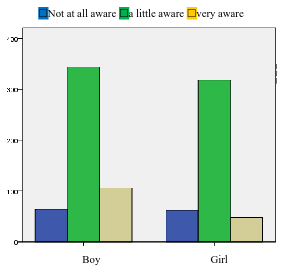

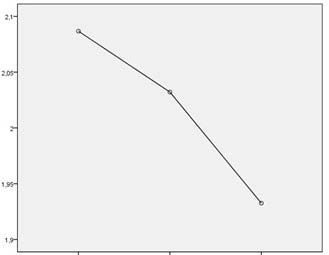

In a recent research it was found that girls participate equally in the sits-in but do not accept aggressive actions and the damages that happen during the sits-in and characterize frequently nonconventional political demonstration (????????????, ????????, ???????????, 2012). In this research chi square test was used (x 2 ) in order to ascertain the relation between sex and youth demonstration. Results show statistical significant differences in the tendency for protestations and pupils' sex [?2=27.367, df=3, p<0,000]. The boys participate in sits-in in a greater percentage (14,4%) than the girls (11%). The differences in the other question that takes part in the index are greater showing that the girls participate less in provocative actions. The boys act in this way in 18.3% percentage whereas girls' corresponding percentage is only 7.6%. (?2=34.616. df=3, p<0,000). The following charts show the results analytically: This opinion is in accordance with the correlation between sex and pupils' point of view about their awareness about politics. Analysis showed that the 20.6% of boys in comparison with the 11.2% of girls believes that it is very informed in relation with issues about politics (?2=15.172, df=2, p=0,001<a). Chart below shows the distributions:

Chart 5 : Correlation between sex and politics awareness Finally, one fact that confirms the view that girls are not interested in politics as boys is time dedicated to informational programs about politics. Statistical analysis showed that on average boys watch more political programs than girls (boys mean=1,34, sd=0, 728 versus girls mean=1, 16, sd=0,548).

In this research it was examined the impact of the type of school on youth demonstration. As it was noted before three types of schools participated: gymnasium, Lyceum and vocational school. It was used chi square statistical test (x 2 ) which resulted that there is statistical significant difference between the type of school and levels of youth protestation (?2=57.439, df=6, p=0,000<a). Pupils from vocational schools in a percentage of 10.4% are more provocative towards their teachers than the pupils from gymnasia (3.6%) and lyceums (3.7%). Also as their participation in sits-in and demonstrations is concerned, pupils from vocational schools participate less than the pupils of gymnasia and lyceums: 55. 1% of pupils from vocational schools have never participated in such political actions in comparison with 44.6% of pupils from gymnasia and 48.4% of pupils from general lyceums (?2=12.935, df=6, p=0,004<a).

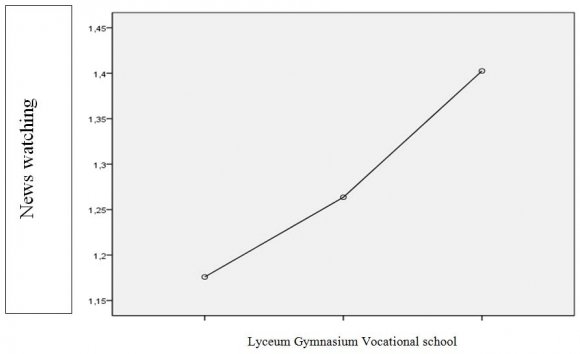

Aiming at the explanation of the behavior of vocational school pupils, the relation between pupils and informational programs about politics was examined. Statistical analysis with multiple comparison test using Bonferroni test, shows that pupils from vocational schools have incomplete awareness about Nevertheless ANOVA test in relation with watching of informational programs about politics and news show that pupils from vocational schools watch on average more TV in comparison with pupils from gymnasia and general lyceums (F=8.940, df=2, p=0,000<a). Test Tukey HSD resulted that pupils from vocational schools watch more TV with a mean difference of 7.205 (p<0.000).

9. Chart 7 : Correlation of type of school and news watching

Finally, statistical analysis about the impact of performance grade on youth political demonstration showed that there is no correlation (pearson coefficient=-0.043). This fact shows that this tendency is not a characteristic of pupils with a poor performance.

10. V. Conclusion

This research aimed at examining pupils' political demonstration as a result of their political socialization process within schools. It was based on a questionnaire and a sample of 960 pupils from schools of central Macedonia.

One of the findings of this research is the fact that male pupils participate more than female pupils. It has to be noted that previous researches concluded that both sexes participate equally. Additionally female pupils are not interested in politics nor watch informational programs about politics on mass media. Moreover, regarding the type of school, pupils from vocational schools tend to provoke more their teachers in comparison with their colleagues from gymnasia and lyceums. It has to be noted that watching informational programs about politics on TV has an important impact on the tendency to protest either in the form of sits-in of The final conclusion of this research agrees with previous researches that claimed that sits-in take place because of pupils' minorities without the use of democratic procedures. In other cases and especially in issues that concern pupils' sex and type of school there is a disagreement due to the fact that differences were observed.

It is evident that sits-in and generally public school depreciation are not a social movement. This is because a social movement is characterized by collective discipline, organization ideological program and a majority basis. None of these features does not apply of course here. Sits-in are an "abstract negation" due to the fact that they undermine the foundations of the educational system without substituting it with a viable alternative solution. The rejection of the school institution acts in a corrosive and not in constructive way.

11. Bibliography

| Frequency Percentage | ||

| Urban | 236 | 24,6 |

| Semi-urban | 509 | 53,0 |

| Rural | 215 | 22,4 |

| Total | 960 | 100,0 |

| Frequency Percentage | Cumulative Percentage | ||

| 50 to 24 years | 13 | 1,4 | 1,6 |

| old | |||

| 23 to 17 years | 258 | 26,9 | 32,5 |

| old | |||

| 16 to 14 years | 430 | 44,8 | 84,2 |

| old | |||

| 13 and below | 132 | 13,8 | 100,0 |

| Total | 833 | 86,8 | |

| Missing | 127 | 13,2 | |

| Total | 960 | 100,0 | |

| and 4 presents the frequencies of the |

| pupils according to the type of school they attend as |

| well as their grade: |

| Frequency Percentage | ||

| Lyceum | 416 | 43,5 |

| Gymnasium | 283 | 29,6 |

| Vocational School | 257 | 26,9 |

| Total | 956 | 100,0 |

| Missing | 9 | ,4 |

| Total | 960 | |

| Class | Frequency Percentage | |

| ? Lyceum | 217 | 23,1 |

| ? Lyceum | 147 | 15,7 |

| C Lyceum | 292 | 31,1 |

| ? Gymnasium | 96 | 10,2 |

| ? Gymnasium | 50 | 5,3 |

| C Gymnasium | 137 | 14,6 |

| Total | 939 | 100,0 |

| Missing | 21 | |

| Total | 960 | |

| Father | Mother | |||

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | |

| Self-employed | 187 | 19,5 | 129 | 13,4 |

| Freelance | 125 | 13,0 | 71 | 7,4 |

| Employer (employs up to 5 persons) | 67 | 7,0 | 50 | 5,2 |

| Employer (employs more than 5 persons) | 42 | 4,4 | 20 | 2,1 |

| Civil servant (lower position) | 15 | 1,6 | 36 | 3,8 |

| Private employee (lower position) | 40 | 4,2 | 59 | 6,1 |

| Civil servant (medium position) | 114 | 11,9 | 122 | 12,7 |

| Private employee (medium position) | 109 | 11,4 | 104 | 10,8 |

| Private employee (senior position) | 47 | 4,9 | 36 | 3,8 |

| Civil servant (senior position) | 54 | 5,6 | 29 | 3 |

| Missing | 160 | 16,7 | 304 | 31,7 |

| Total | 960 | 100,0 | 960 | 100,0 |

| Father | Mother | |||

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | |

| Up to primary school certificate | 112 | 13,2 | 40 | 4,7 |

| Up to gymnasium certificate | 133 | 15,7 | 137 | 16,2 |

| Up to lyceum certificate | 288 | 34,0 | 322 | 38,2 |

| Technological Institute degree | 196 | 23,2 | 174 | 20,6 |

| University degree | 91 | 10,8 | 132 | 15,6 |

| Master's | 13 | 1,5 | 24 | 2,8 |

| PhD | 13 | 1,5 | 15 | 1,8 |

| Total | 846 | 100,0 | 844 | 100,0 |

| Missing | 114 | 116 | ||

| Total | 960 | 960 | ||

| Have you ever participated in a demonstration or a | Do you provoke a teacher with whom you | |

| sit-in? | disagree? | |

| Chi-Square | 521,107 a | 501,671 b |

| df | 3 | 3 |

| Asymp. | ,000 | ,000 |

| Sig. |