1.

Professor Dr. Kazi Abdur Rouf he profit-maximizing capitalism can never deliver equitable distribution of income in the society. Today's world, 85 individuals own more wealth than all those in the bottom half. Top half population of the world own 99% the wealth of the world, leaving only 1% for the bottom half. Out of 7.3 billion world population, the numbers of young population are around 1.8 billion who are job seekers (Grameen Dialogue 93, 2014, pp. 3). It may get worse because technology will remain under the control of the people at the top (Yunus, 2014). In capitalism, maximizing personal profit is the core of economic rationality. Therefore, government and the non-profit sector are necessary, but insufficient to address society's greatest challenges. The social economic missions blend businesses are necessary to address the private sector monopoly profit maximizing exploitative market oppressions. As the public sector funding is limited and this sector is inefficient to serve the community, hence social economy activities and services are crucial for public wellbeing services. Hence M. Yunus (2013) provokes for social business that must create value for society, not just shareholders. Now the world needs, for example, systemic challenges require systemic solutions and the beneficial corporation (B Corp) movement, CIC, Grameen Social Business, Community Economic Development agencies and social enterprises that offer a concrete, market-based and scalable solution. The emergence of social enterprises, and the range of goods and services social entrepreneurial businesses produce, has evolved against the milieu of capitalist states reforms towards a mixed economy of private, public and third sector provider. BASF Grameen manufactures malaria nets is working to address the issue of mosquito bites and protect people from malaria disease. Social entrepreneurs are influencing the regulatory and investment environments to hold businesses more accountable to their social and environmental performance and to support social enterprises. These social entrepreneurs reflect enlightened human values (Jack, Mook, & Armastrong 2009;and Yunus, 2014).

In the revenue generated socioeconomic twisted business framework, social enterprises have emerged as an effective tool to deliver policy objectives in two key areas of social and economic policy: Service delivery and social inclusion. Hence, many scholars think social enterprises pioneer in leading to social cohesion and social inclusion. Its dominant feature is civil society development. Social enterprises can support the financial and regulatory sustainability of civil society initiatives aimed at supporting disadvantaged groups and develop partnerships for social innovation. A social enterprise has two goals: (1) to achieve social, cultural, community economic and environmental outcomes; and (2) to earn revenue. Social enterprises are businesses whose primary purpose is the common good. The social entrepreneurs use methods and disciplines and the power of the marketplace to advance their social, environmental and human justice agendas. However, social enterprises are revenuegenerating businesses with entwined -social and economic objectives following capitalism.

2. II.

3. Different Names of the Revenue Generated Social and Economy Missions Twisted Businesses

Social enterprises, social businesses, social economy, social entrepreneurships, Social Capital Partners, social clubs, social financing, social housing, social investment organizations, and social purpose businesses are revenue generated social entrepreneurial businesses. The Community Investment Corporations (CIC) UK based, L3C-USA based, Beneficial Corporations (B-Corporation) USA, social entrepreneurships, Social Capital Partners, Venture Philanthropy, Farmers Cooperatives, Commercial Cooperatives and Financial Cooperatives (credit unions) are latest models social economic organizations. Other forms of social entrepreneurial organizations are members based organizations (workers cooperatives, trade unions), non-profit mutual associations, professional associations, business association, housing cooperatives, networking organizations and revenue earned cultural associations.

Moreover, the Chamber of Commerce, mutual insurance, not-for profit organizations, nongovernmental organizations, community enterprises, community economic development projects, micro-finance institutions (MFIs), commercial non-profits are also termed social enterprises. The civil society organizations, community foundations, enterprising nonprofit programs, non-profit organizations (NPOs), selfhelp groups, Solidarity Economy belongs to social economy agencies. All theses social enterprises perform social and economic objectives under different framework, different strategies and different funding models.

4. a) Entrepreneurship

The word "entrepreneur" originates from the French entreprendre and the German unternehmen, both of which mean literally "to undertake," as in accepting a challenging task. They refer to the groundbreaking development of the concept by Cantillon (1680-1734) and Say (1767-1832) (see, e.g., Dees, 1998: 2f). An entrepreneur is a risk taker person driven by the burning desire to put his business idea into action. He is ready to tackle difficulties, to experiment boldly, to work long hours, and to experience personal setbacks and disappointments without becoming discoursed. He is not satisfied until his project is implemented successfully, producing the desired results-either financial reward or social improvement. Entrepreneurship is an integral part of human nature. Social business offers a new and exciting way of expressing it. Social business also provides an outlet for the creativity that millions of people harbour within themselves.

5. b) Social Entrepreneurship

'Social entrepreneurship' describes an initiative of social consequences created by an entrepreneur with a social vision because it is exercised by individuals. Entrepreneurship is best thought of as an extended activity which may well be carried out by a team or a group of people (Stewart, 1989). To be an entrepreneur may therefore mean being an individual, a member of a group, or an organization who/which carries out the work of identifying and creatively pursuing a social goal. In fact, some scholars even refer to organizations that pursue both commercial and social objectives as hybrids (Davis, 1997). In a sense, these hybrids pursue two bottom lines, one of which deals with profit while the other deals with social value.

According to Bornstein and Davis (2010) social entrepreneurs is a process, a way to organize problemsolving efforts. Social entrepreneurs carry risks. They have relationship between the individual and society. Social Entrepreneurship to be understood with appropriate flexibility-its aims at creating social value, either exclusively or at least in some prominent way; (2) its shows a capacity to recognize and take advantage of opportunities to create that value ("envision"); (3) it employ(s) innovation in creating and/or distributing social value; (4) It is willing to accept an above-average degree of risk in creating and disseminating social Year 2015 ( E )

value. According to Peredo & McLean (2006) the social entrepreneurship allows the entrepreneur to balance the interests of many people and remain true to the mission in the face of moral intricacy. Social entrepreneurs are excel at recognizing and taking advantage of opportunities to deliver the social value that they aim to provide. Social entrepreneurs show risk-tolerance, innovativeness, and pro-activeness are not showed by commercial entrepreneurs. Social entrepreneurs have "social value" i.e. contribute well being in a given human community. However, this definition allows not wealth creation.

In contrast with social entrepreneurs, social business is a very specific type of business-a non-loss, non-dividend Company with a social objective. A social business may pursue goals similar to those sought by some social entrepreneurs, but the specific business structure of social business makes it distinctive and unique. Hence social entrepreneurship and social business should be similar concept. Social business is not a non-profit organization. The foundation, for example, would get its money back and be able to use it for some other worthy purpose. However, it is not possible in the traditional NGOs who could own a social business. By contrast, a social business is designed to be sustainable. This allows its owners to focus not on asking for donations, but for investment. However, it would need to be separated from the NGOs for legal, tax and accounting purposes.

Social Entrepreneurship has many benefits like systematically identify people with innovative ideas and practical models for achieving major societal impact and to develop support systems to help them achieve significant social impact. Social entrepreneurship shifted to organizational excellence. It is contagious (Bouchard, Ferraton, & Michaud (2006) Below the paper describes different concepts of social entrepreneurial organizations, their different financial and legal models, and their contributions to different societies.

6. c) Social Economy

According to Quarter et al. (2009) the social economy is a bridging concept for organizations that have social objectives central to their missions and their practice, and either have explicit economic objectives or generate some economic value through the services they provide and purchases that they undertake. The majority social organizations are charities in Canada (Lasby, Hall, & et al., 2010;and Salamon (1999) termed it a form of mobilizing economic resources towards the satisfaction of human needs. The SEOs have democratic principles of one member/one vote with very high participation rates. It is serving the public as well as mutual associations, cooperatives making connection to people and the communities (Quarter et al., 2009

7. ( E )

Employment Summit in Quebec in 1996 define social economy objectives are serves to members and community. Here SEOs managements are independent (Chantier de 1'economic sociale, 2005). The Human Resources and Social Development Canada (HRSDC, 2005) defined the social economy is a grass roots entrepreneurial, not-for-profit sector, based on democratic values that seek to enhance the social, economic conditions of communities and focus on their disadvantaged members. The Walton Council, Belgium, termed it 'social market economy'. These social entrepreneurships have "double bottom line" means placing equal emphasis on profit and social benefit. However, there are challenges found in CBEs like maintaining a balance between individual and collective needs, and among economic and social, goods.

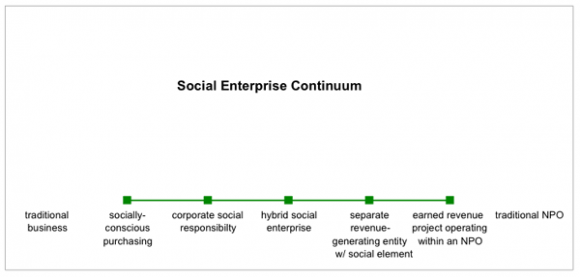

According to Mendell & Neamtan (2010) social economy is a process of re-engaging government in new ways and working across boundaries to participate in new policy design. The figure below diagrammatically describes the intersection between the private sector, public sector and social-economic organizations three areas. The common characteristics of the social economy organizations include social and economic missions, social ownership, volunteer/social participation, and civic engagement. These social economic missions blend organizations are very important to address multinational corporations, private sectors monopoly profit maximizing exploitative market and limited public sector funding and public sector inefficiency to serve the community social economy. They are working for the well-being of the disadvantaged people in the society. These organizations created huge employment in the different countries.

Schugurensky & McCollum (2010) mention that in Canada and internationally, the social economy makes a significant contribution to the social, economic, cultural and environmental well-being of communities. The Human Resources and Social Development (HRSD) in Canada (2005) acknowledges that 'the Government of Canada is just beginning to understand the power and potential of social economy enterprises and organizations.' In Bangladesh, MFIs are intensively working for the poor and they are popular to them; on other pole Canadian Charitable organizations, civil society organizations, credit unions are providing service, meet needs of the citizens. However, there are fewer interactions among public sectors and social economic organizations. Many social organizations, community economic programs gets funding from public sectors in Canada, which are less in Bangladesh. Currently many private sectors opened their foundations and funds to work with social and economic missions.

8. d) Social Business

Social businesses are social-purpose businesses. They have blended social and economic values. Social entrepreneurship represents fundamental reorganizations of the problem solving work of society-a shift from control-oriented top down policy implementation to responsive, decentralized institution building. They provide services and do businesses with the bottom of the pyramid (Prahalad 2003). They are dogooders, many made self-sacrifice. For example, the Bangladesh Ashraon Housing Project has funded by public sector and this project is intensively monitored by the project gross root workers.

Revenue-Generating Social and Economic Mission-Entwined Praxis of Organizations Quarter, Mook & Armstorng (2009) also included social economy organizations that are incorporate or non-incorporate cooperatives, social enterprises, community development initiatives, public sector nonprofits, non-profit member associations and civil society organizations. Non-profit and nongovernmental organizations refers them to social, social purpose and citizen-sector organizations. and social entrepreneur refers to founders of organizations even it s not legally structured as a profit seeking entity (Bornstein & Davis (2010).

According to Muhammad Yunus (2013) a social business is a Non-loss, Non-dividend Company designed to address a socioeconomic objectives. These organizations' profits are used to expand the company and to improve the product/service. This model has grown from the work of Grameen sister organizations and others following social principles. Social business is a cause-driven business. In a social business, the investors/owners can gradually recoup the money invested, but cannot take any dividend beyond that point. Purpose of the investment is purely to achieve one or more social objectives through the operation of the company, there is no personal gain is desired by the investors. The social business organization must cover all costs and make revenue, at the same time achieve the social objective, such as, healthcare for the poor, housing for the poor, financial services for the poor, nutrition for malnourished children, providing safe drinking water, introducing renewable energy, etc. in a business way. The impact of the social business on people or environment is worthy, rather than maximizing profit solely. The objective of the social business organization is to achieve social and economic goals.

9. 73

Year 2015

10. ( E )

It is not for maximizing profit, but for maximizing social benefit. It is not a charity. It is not part of corporate social responsibility. It does not fall within the category of NGO or Cooperatives. It is distinct from social entrepreneurship in strict sense of the term. It is a sustainable business proposition and it is a market based solution for poverty reduction. It is about combining business principles with social objectives. It is not social objectives versus profit objectives rather it has combination of the two. It is designed and operated as business enterprise with products, services, customers, markets expenses and revenues, but with the profit maximizing principle replaced by social benefit principles.

11. e) Features and Goals of Social Business

A social business is generating enough surpluses to pay back the invested capital to the investors as early as possible. It generates surplus for expanding the business, for improving the quality of business, to increase efficiency of the business through introducing new technology, to innovative marketing to reach the deeper layers of low-income people and disadvantaged communities. There are eleven features of Social Business Organizations:

12. h) Community Based Enterprises (CBEs)

Community Based Enterprises (CBEs) often constitute a culturally appropriate way of addressing problems such as poverty-alleviation. According to Peredo & Chrisman (2006) the community based enterprises are typically rooted in community culture, natural and social capital is integral and inseparable from economic considerations, transforming the community into an entrepreneur and an enterprise. The CBEs are important when public sectors and private sectors development efforts have been largely unsuccessful. In such situation, social economy scientists encourage the creation of small businesses owned by the community. The CBEs are alternative socioeconomic model where the community acts as an entrepreneur when its members acting as owners, managers and employees, create or identify a market opportunity and organize themselves in order to respond to it. CBEs are managed and governed by the people, rather than by the government. CBEs structures are designed to be participatory, not only representative.

Here community may come together to solve its problems. However, CBEs success depends on Social Capital: there people depend on social relations to fulfill their needs.

Bourdieu (1997), Putnam (1973) say that community networks allow resources to be pooled, actions to be coordinated, and safety nets to be created that reduce risks for individual community members. They are based on available community skills, multiplicity of goals-economic, social and environmental benefit and will be directed by profits, but dependent on community participation (Peredo & Chrisman, 2006). However, there are challenges found in CBEs like maintaining a balance between individual and collective needs and among economic, social, environmental and cultural goods.

13. i) Civil Society Organizations

Civil Society Organizations are primarily associations and organizations representing the mutual needs of a membership in the society. They work for professional interests, labour rights, recreation, sports, religion and environment. For example, Bangladesh Medical Association, Bangladesh Agriculturalist Association etc. are associations lobbying for medical doctors and agriculturalists interest. In Canada Farmers Cooperatives organized for to lobby for their products, rights and to link their products to the local and the international markets. The Canadian Chamber of Commerce and the Dhaka Chamber of Commerce in Bangladesh work for promoting trade and commerce of the respective countries although performance is different of each of them. Desjardins, a credit union in Canada, is successful financial credit unions are working across Canada. Such a model is absent in Bangladesh. Milk producers' cooperatives are smoothly functioning in Bangladesh. These organizations have social objectives, social ownership, the assets belong to members, social participation and have civic engagement.

14. III. Difference between Social Entrepreneurs and Business Entrepreneurs

Social entrepreneurs, the bottom line is to maximize some form of social impact, usually by addressing an urgent need that is being mishandled, over looked or ignored by other institutions. For business entrepreneurs, the bottom line is to maximize profits or shareholders wealth, or to build an ongoing, respected entity that provides value to customers and meaningful work to employees. Social entrepreneurs earn profit through social enterprises and business people are concerned about social responsibility. Social entrepreneurs involve elements of newness and dynamisms. They are clean-tech, green-tech (Greg Dees, 2002). According to Dees (2001) social entrepreneurs are one species in the "genus entrepreneur", meaning social entrepreneurs are a subgroup of entrepreneurs. Peredo and McLean (2006) assert that 'business methods' social economic entrepreneurs approach applying principles from forprofit business without neglecting the core mission. The private sectors are maximising profit making, tax evasion, loan defaults and share scandals indicates poor ethical performance of private businesses. They Year 2015

15. ( E )

provide sub-standard poor quality goods to market that create health hazards to people.

To better understand social entrepreneurship, Austin et al. (2006) distinguished between two types of entrepreneurship. In their framework, commercial entrepreneurship represents the identification, evaluation, and exploitation of opportunities that result in profit. In contrast, social entrepreneurship refers to the identification, evaluation, and exploitation of opportunities that resulting social value. Organizations can pursue commercial entrepreneurship, social entrepreneurship, or some combination of both.

IV. What's a Social Enterprise?

According to Organization for Economic Cooperation Development (OECD) Social enterprises have developed from and within the social economy sector, which lies between the market and the State and is often associated with concepts such as 'third sector' and 'non-profit sector'. The social enterprise concept does not seek to replace concepts of the non-profit sector or social economy. Rather, it is intended to bridge these two concepts, by focusing on new entrepreneurial dynamics of civic initiatives that pursue social aims. Social enterprises produce these benefits while reducing the draw on public and philanthropic funds. They earned income or replace grants and donations to produce a dramatically higher return on investment (ROI). For example, a non-profit that earns 50% of its budget through its social enterprise is effectively matching every dollar of "public income" with a dollar of "marketplace income", doubling the social return on investment (ROI) of those public dollars. Canadian government sometimes offer such benefits to community economic development programs.

Social enterprise is emerging as sector between the traditional worlds of government, nonprofits and business. It addresses social concerns. However, it is more efficient than government to solve every social problem (Hall, 1998) As social needs continue to spike in light of shrinking government budgets, employment rolls, and social safety nets, social enterprise is emerging as a self-sustaining, market-based, businesslike and highly effective method of meeting social needs.

Social enterprise also known as social entrepreneurship, broadly encompasses ventures of nonprofits, civic-minded individuals, and for-profit businesses that can yield both financial and social returns. According to Social Enterprise Canada "Social enterprises are businesses owned by non-profit organizations, that are directly involved in the production and/or selling of goods and services for the blended purpose of generating income and achieving social, cultural, and/or environmental aims. Social enterprises are one more tool for non-profits to use to meet their missions to contribute to healthy communities" (Social Enterprise Council of Canada, 2015). From the above discussion, it is found that social enterprise should have a clear social and/or environmental missions set out in their governing documents. It generates the majority of their income through trade and reinvests the majority of their profits. It is to be autonomous of state and it has interests of the social mission.

Social enterprises are also emerging in the provision of community services, including in the educational, cultural and environmental fields. The key economic and social elements are as follows: a) Economic Criteria 1) Unlike traditional non-profit organisations, social enterprises are directly engaged in the production and/or sale of goods and services 2) The financial viability of social enterprises depends on the efforts of their members, who are responsible for ensuring adequate financial resources, unlike most public institutions 3) Activities carried out by social enterprises require a minimum number of paid workers, even if they may combine voluntary and paid workers. Social criteria 4) Social enterprises are the result of an initiative by citizens involving people belonging to a community or to a group that shares a certain need or aim 5) Decision making rights are shared by stakeholders, generally through the principle of 'one member, one vote'. Although capital owners in social enterprises play an important role, decision-making power is not based on capital ownership 6) Social enterprises are participatory in nature in the management of activities 7) Social enterprises include organisations that totally prohibit the distribution of profits and organisations such as co-operatives, which may distribute their profit only to a limited degree. Social enterprises therefore avoid profit maximising behaviour, as they involve a limited distribution of profit 8) Social enterprises pursue and promote social responsibility at local level.

16. b) Social Enterprise Leverage (Weight)

Social enterprises produce higher social returns on investment than other models. A classic employment-focused social enterprise, for example, might serve at least four public aims: fiscal responsibility-it reduces the myriad costs of public supports by providing a pathway to economic selfsufficiency; it provides public safety-by disrupting cycles of poverty, crime, incarceration, chemical dependency and homelessness. Moreover social enterprises generate economic opportunity and create jobs in communities and ensure social justice-it they give a chance to those most in need. Social economic organizations could address the above mentioned issues in an accountable and transparent manner because here philanthropic mission is the first place in addition to revenue generation commitment. However, in Canada cooperatives and nonprofits have millions of members and manage millions of dollars every day (Schugurrensky & McCollum, 2010). Therefore, Yunus (2013), Quarter, et al. (2009), Hall (2000), Polany, and Putnam (1996) idea of social business is not an utopian dreams, but viable alternatives to organizing economic enterprises. According to Yunus (2013) social business will not replace traditional business rather it co-exist with traditional business and expand social businesses in the world.

17. Global Journal of Human Social Science

There are three characteristics distinguish a social enterprise from other types of businesses, nonprofits and government agencies:

? It directly addresses an intractable social need and serves the common good, either through its products and services or through the number of disadvantaged people it employs.

Source: BC Centre for Social Enterprise Newsletter April 2015.

? Its commercial activity is a strong revenue driver, whether a significant earned income stream within a non-profit's mixed revenue portfolio, or a for profit enterprise.

? The common good is its primary purpose.

The top five missions of social enterprises are workforce development, housing, community and economic development, education, and heath. Social enterprise business models are equally diverse, including: retail, service and manufacturing businesses; contracted providers of social and human services; feebased consulting and research services; community development and financing operations; food service and catering operations; arts organizations; and even technology enterprises.

18. c) Benefits of Social Business

Social businesses have many advantages. It is lasting. It does not only create employment opportunities, but also create an enabling environment for unleashing the creative capacity and entrepreneurial skill of the youth. However, the financial institutions are designed for the rich in the capitalist society. Institutions designed for the rich will not do any good to the poor. Yunus (2014) hopes if people want creating a world without unemployment, micro credit and social business services to poor are essential. Jack, Mook, and Armstrong (2009) think social economy can address social problems in the capitalistic society.

19. d) Social Business Cooperatives

Many people are confused with a social business is a cooperative. A cooperative is owned by its members. It is run for profit to benefit the membershareholders. D. et al. Owen (2000) had made clear cooperative social objectives: to empower the poor, to encourage self-sufficiency, and to promote economic development. Today, many co-ops still create social benefits. For example, in Canada, there are housing coops that make affordable homes available to workingclass people, food co-ops that bring healthy nutrition within the reach of city dwellers, and banking co-ops that provide financial services to consumers who might otherwise be underserved.

In Canada Farmers Cooperatives organized for to lobby for their products, rights and to link their products to the local and the international markets. They co-operate each other. Mondragon is Spain's largest workers cooperative with a number of integrated functions including manufacturing, banking, and education. It is interesting to note that the evolution of Mondragon includes the formation of an educational institution, which is closely linked to the human resources needs of both manufacturing and service cooperatives within Mondragon (Greg McLeod (2012).

Cooperatives are organizations that are owned by the members who use their services or purchase their products ( services, arts, and culture, retail sales and in agricultural goods and services. There were 5,753 non-financial cooperatives, with 5.6 million members, 85,073 employees, $27.5 billion revenues and $ 17.5 billion assets (Cooperative Secretariat 2007). 12 million Canadians are associated with cooperatives; there are 1,140 credit unions with 3,400 service locations, 10.5 million members, 64,600 employees and 248.8 billion in assets. Financial co-operatives transact 12.7% of the Canadian financial GDP for the financial sector (Mook, Quarter & Ryan, 2010). The co-operatives have tremendous contribution to the well-being and economic growth of Quebec. Desjardins, a credit union in Canada, is successful financial credit unions are working across Canada, which is absent in Bangladesh.

However, Comilla Cooperatives in Bangladesh were famous in the world in 1960s. Its model rapidly replicated in Bangladesh in 1970s and in early 1980s by the government become mission drift. In Bangladesh there are no private daycare centers, private sports centers, or public shelters. However, Arang, Karu Palli, Nari Prabatana Shops collect embroidery products, handmade toys, souvenirs from the rural poor women that create many employment in the rural poor, but they are running under the shadow of BRAC and BRDB and Nari Pakka respectively, but they are earning money selling their products in a market place.

Co-op by definition is a socially beneficial activity. An example is the Self-Employed Women Organization's (SEWA), a trade union that helps selfemployed Indian women pursue the goals of 'full employment': work security, income security, food security, health care, child care and shelter. SEWA has now over 900,000 members throughout India. These women select their own leaders, and effectively run the organization for the benefit of the rank-and-file.

20. e) Grameen Social Businesses

Grameen social businesses have clear focus on eradicating extreme poverty combined with the condition of economic sustainability has created numerous models with incredible growth potential. The framework of the Grameen social business is based on 7 principles. Grameen Social Businesses seven principles are as follows:

1. Business objective will be to overcome poverty, or one or more problems (such as education, health, technology access, and environment) which threaten people and society; not profit maximization. 2. Financial and economic sustainability.

21. Investors get back their investment amount only. No

dividend is given beyond investment money. 4. When investment amount is paid back, company profit stays with the company for expansion and improvement. 5. Environmentally conscious.

6. Workforce gets market wage with better working conditions. 7. ...do it with joy.

Grameen social business targets business opportunities neglected by traditional profit maximizing companies in Bangladesh. The present economic system is not designed to have any moral responsibility. Discussion on moral responsibilities is an after-thought. According to Yunus (2014) moral issues were never included in the present economic system. He said that social business is a new kind of business which is based on selflessness, replacing selfishness, of human being. Conventional business is personal-profit seeking business (Grameen Dialogue 93, 2014). The social business is a non-dividend company to solve human problems. Owner can take back his investment money, but nothing beyond that. After getting the investment money back all profit is ploughed back into the business to make it better and bigger. It stands between charity and conventional business and carried out with the methodology of business, but delinked from personal profit-taking (Yunus, 2013).

Grameen Bank is inspiring the second generation of Grameen Bank borrowers' families to believe that they are not job seekers, they are job givers. Poor can be a business person by using loans. According to Yunus, there are two types of business (1) Traditional business-profit making and dividend distribute to business owners/shareholders; (2) Social business -everything for the benefit of others and nothing is for the owners-except the pleasure of serving humanity. The second kind of business built on the selfless part of human nature.

The social business might be described as a 'non-loss, non-dividend company' dedicated entirely to achieving a social goal. According to Yunus (2013) a social business is a selfless business whose purpose is to bring an end to a social problem. In this kind of business, the company makes a profit-but no one takes the profit.

22. Revenue-Generating Social and Economic Mission-Entwined Praxis of Organizations

The Yunus Center Social Business Design Lab (YCSBDL) is promoting and supporting grameen social businesses. It facilitated many workshops on Grameen type social businesses. Currently Nabin Uddug social business projects are operated and invested through Grameen sister organizations-Grameen Shakti Samajik Babsha, Grameen Trust, Gramen telecom Trust, Grameen Shikka, Grameen Kallayan, Gramen Motsha Foundation, Gramee Krishi Foundation. Kazi A. Rouf, the author of the paper, visited many Nabin Uddug social businesses in Bangladesh. Moreover, Mr. Rouf has received many feedbacks from the Nabin Uddugktta entrepreneurs, local young entrepreneurs and university/college students. The Nabin Uddug social business campaigns by Professor Muhammed Yunus have revolutionized in Bangladesh.

23. Global Journal of Human Social Science

24. Types of Grameen Social Businesses

There are two kinds of social business. (1) One is a non-loss; Non-dividend Company devoted to solving a social problem and it is owned by investors who reinvest all profits in expanding and improving the business. The Grameen social businesses include Grameen Danone, Grameen Veolia Water, BASF, Grameen, and Grameen Intel has been of this type 1 social businesses. First Grameen Social Businesses Grameen Danone, a joint venture yogurt company is created in Bangladesh that produces, markets and distributes its products much the same as any for-pro yogurt company. Yogurt container is biodegradable-no plastic is allowed. Grameen Veolia, another joint venture type-1 Grameen social business, water treats surface water for contaminants and then pipes it to where it is needed. The examples mentioned above fit into this category. Yunus calls all these businesses as 'Type 1 social businesses'(Yunus, 2013).

The second kind is a profit-making company owned by poor people, either directly or through a trust that is dedicated to a predefined social cause. A social business owned by the poor benefits the poor by generating income for them directly. Yunus call it Type 11 social business. Grameen Bank, which is owned by the poor people who are depositors and customers, is an example of this kind of social business. The Otto Grameen textile factory owned by Otto Trust use the proceeds to benefit the people of the community where the factory is located. Unlike a non-profit organization, a social business has investors and owners. Moreover, in a Type 1 social business, the investors and owners don't earn a profit, a dividend or any other form of financial benefit. The investors in a social business can take back their original investment amount over a period of time they define. Personal financial benefit has no place in social business. They serve as a touchstone that is at the heart of social business idea.

Muhammad Yunus (2013) uses the term 'Impact investing', means for an investment strategy whereby an investor proactively seeks to place capital in businesses that can generate financial returns as well as an intentional social and/or environmental goal. This concept of combined financial and other benefits is known as Triple-bottom line or blended value. Impact investing is differentiated from socially responsible investing in that an investor will proactively seek investments that generate both financial as well as specific social and/or environmental returns. Grameen social business aims to create economic opportunities for the Children of Grameen Bank's members through the Nabin Udyokta (NU) program. Grameen Babsha Bikas (GBB), is a key partner of implementing Grameen social businesses in Bangladesh. GBB (Grameen Byabosa Bikash), establish in 2001, provides technical assistance and training support along with monetary support to the new entrepreneurs in Bangladesh. GBB is working towards poverty eradication by creating New Entrepreneurs. GBB has started implementing social business such as fishing farm, duck farm, nursery, toy factory, bamboo mat works in Bangladesh since 2001.

25. a) Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

Companies became more involved in charitable activities and started reporting on their efforts to improve conditions for their employees and other stakeholders. The idea of sustainable business practices broadened this concept with a stronger focus on environmental impact and specific metrics, such as an organization's carbon footprint. However, the suspicion persisted that there were some companies who treated CSR and sustainability primarily as a marketing tool that was not well integrated with the operations of the company. This often resulted in accusations of "green washing" and impacts on society were questioned. At the same time, executives in many companies struggled to justify investments in CSR and sustainability when the link to increased profits was difficult to establish.

26. b) Community Interest Corporation (CIC), an emerging Alternative Social Enterprises Structure

A CIC is a new type of company introduced by the United Kingdom government in 2005 under the Companies (Audit, Investigations and Community Enterprise) Act 2004, designed for social enterprises that want to use their profits and assets for the public good. CICs are working for the benefit of the community. The CICs businesses surpluses are principally reinvested for that purpose in the business or in the community, rather than being driven by the need to maximise profit for shareholders and owners. CICs tackle a wide range of social and environmental issues and operate in all parts of the economy. By using business solutions to achieve public good, it is believed that social enterprises have a distinct and valuable role

27. Revenue-Generating Social and Economic Mission-Entwined Praxis of Organizations

The concept of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) was an earlier and still quite prevalent approach to generating societal benefits through business. CSR arose when companies began to notice that an increasing number of customers cared about more than just price and quality; they cared about a company's demonstrated commitment to social and environmental issues as well. However CSR is a concept that is working in capitalism.

One of the alternative legal structures now emerging is the community interest company (CIC) in UK. This is a new legal vehicle for business available since 2005; the British government refers it as 'social enterprise'. According to UK authorities, 'CIC' will be organizations pursuing social objectives, such as environmental improvement, community transport, fair trade etc. Social enterprises are playing an increasing role in empowering local communities and delivering new, innovative services at local level.

Year 2015

28. ( E )

to play in helping create a strong, sustainable and socially inclusive economy. CICs are diverse. They include community enterprises, social firms, mutual organisations such as co-operatives, and large-scale organisations operating locally, regionally, nationally or internationally.

29. c) Legal Forms and Social Objectives of CIC

CICs must be limited companies of one form or another. A CIC cannot be a charity, an incorporated profit organization (IPO) or an unincorporated organisation. A charity can convert to a CIC with the consent of the Charity Commission. In so doing it will lose its charitable status including tax advantages. A charity may own a CIC, in which case the CIC would be permitted to pass assets to the charity. CICs are more lightly regulated than charities but do not have the benefit of charitable status, even if their objects are entirely charitable in nature.

Those who may want to set up a CIC are expected to be philanthropic entrepreneurs who want to do good in a form other than charity. This may be because CICs are specifically identified with social enterprise. They are looking to work for community benefit with the relative freedom of the non-charitable company form to identify and adapt to circumstances, but with a clear assurance of not-for-profit distribution status. The definition of community interest that applies to CICs is wider than the public interest test for charity.

A Government regulator is responsible for examining each proposed CIC to make sure it passes what's called the Community Interest Test (CIT). This means satisfying the regular that the purposes of the CIC 'could be regarded by a reasonable person as being in the community or wider public interest.' The community interest test (CIT) that a CIC must pass is less strict than the rules a charity must meet in the UK. However, the CIC also does not enjoy the tax benefits that a charity gets. A CIC pays taxes on its revenues in much the same way as any ordinary business gets. A CIC pays taxes on its revenues in much the same way as any ordinary business. Also, the assets held or generated by the CIC, including any surplus of revenues over expenses, are subject to what is called an asset lock. This is a legal requirement that the assets of the CIC be used solely for community benefits. Like a profitmaximizing company, a CIC has one or more owners. A charity can own a CIC; so an individual, a group, or another company. A political party, however; is not permitted to own a CIC.

A CIC can solicit funds from investors and it can even issue shares of stock, just like a traditional corporation. In this respect, a CIC is similar to Yunus concept of a social business. Grameen Danone and Grameen Veolia Water, for example, are both owned jointly by the Grameen companies and their parent corporations-Danone and Velia Water, respectively. However, unlike a social business, a CIC may pay dividends to shareholders (this is the exception to the asset lock rule), through these dividends are limited by law. Currently, the maximum dividend per share is 5 percent above the Bank of England base lending rate, and the total dividend declared in any given year is limited to 35 percent of the company profits. The CIC is a restricted profit company, but it does not qualify to be the kind of social business that Yunus has been promoting. However, a CIC could become a social business; CIC owners and shareholders explicitly and clearly renounced the acceptance of dividends or any other form of profit distribution beyond the amount of investment. As of end of 2009, there were over 3000 CICs registered in the UK. Some have become quite successful and well-known-for example, Firely Solar, which uses sustainable technologies in producing events for organizations ranging from the Glastonbury Music Festival to Greenpeace etc. There is also considerable discuss about creating a similar legal structure in Canada. Paul Martin, ex-Prime Minister described the potential for good of businesses organized for social purposes (Yunus, 2014).

30. d) Low-Profit Limited Liability Company (L3C)

L3C is another type of social enterprise concept developed in USA. The first law establishing the L3C structure was enacted by the state of Vermont in 2008. As of end of 2009, the concept had also been recognized by Michigan, Utah, Wyoming, and Illinois, and considered in North Carolina, Georgia Oregon, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Montana. The crow Indian Nation and Oglala Sioux Tribe also recognize the L3C structure. CIC has been enacted in eight other states-Illinois, Michigan, North Carolina, Maine, Utah, Wyoming, Louisiana, Rhode Island-and two Native American nations-the Crow and the Oglala Sioux since 2009 (Americans for Community Development 2011).

An L3C is a business entity formed to finance socially minded projects and organizations, and may include funds from non-profit or for-profit entities (Witkin 2009). Its purpose is to attract a range of investment sources for socially beneficial, limited-profit ventures, and thereby improve the viability of such ventures. As L3C structures are very new, there are no known examples of an L3C structure to support the financing of the renewable energy (RE project).

The L3C is a variant form of the limited liability Company (LLC), but specifically enables a divergent mix of corporations, individuals, non-profits, and government agencies to organize under one "umbrella" for a charitable or socially beneficial purpose. Like all LLCs, the L3C is essentially a partnership with corporate protection. An L3C can include for-profit or non-profit entities, but has no definitive structure or required participation of any entity type. The L3C can also serve to attract the right foundation with a compatible mission to become a member and use this investment vehicle alternative.

31. Global Journal of Human Social Science

The L3C is a for-profit venture that, under its state charter, must have a primary goal of furthering an exempt purpose. It fits within the definitions in the federal regulations for PRIs (Program Related Investments). Project investments made under an L3C can be used to lower the risk profile or reduce the cost of capital for a particular project. The model essentially turns the venture capital model on its head. L3Cs can develop social and economic purpose missions, making it easier for socially motivated investors to locate the branded L3C that satisfies their needs and investment objectives.

32. e) The L3C and Alternative Energy Funding

As per internal revenue service (IRS) regulations, foundations are required to spend 5% of their net assets on charitable giving every year (Lakamp et al., 2010). The strategy, using primary rate interfaces (PRIs), allows private foundations to make equity investments in for-profit entities. The renewable energy projects rely heavily on various tax benefits to improve the cost of the associated power and induce investment. However, renewable energy projects and the developers utilize the tax benefits to their full value. Accordingly, a separate "tax equity investor" is sought to invest in the project. Because non-profits have no use for tax credits or depreciation, they cannot take direct advantage of the tax benefits. With the L3C structure in place, the tax benefits can be concentrated and absorbed by a tax equity investor that has the "tax appetite" from other businesses to utilize. The ideal project will be able to take advantage of both tax benefits and the low cost of capital provided by the foundation participation. The L3C allows the tax benefits to be fully utilized and thus lowering the cost of energy to the end user by accessing a wider base through foundations and non-profits (Ibid, 2010).

The L3C like the CIC is fundamentally a forprofit company that pursues a social business. Iike other business. An L3C has one or more owners, which can include individuals, charities, or for-profit companies. And like a CIC, an L3C can pay dividends on any financial surplus it generates. However, there are no written guidelines limiting the size of profits and no public regulator is designed to pass judgement on whether a particular L3C is paying profits that are 'excessive'.

Like other limited liability companies, the L3C has a pass-through status in regard to U.S. federal income taxes. That is, the corporation itself pays no income tax. Instead, all items of income, expense, gain, and losses are 'passed through' to the members (owners) of the L3C in proportion to their ownership shares. However, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) rules defining PRIs are complicated and difficult to follow (Yunus, 2013).

The legal and financial structure of the L3C makes it possible for an organization like a foundation to invest money in a business with social purposes and recover its initial investment. However, the difference between the L3C and the social business is the same as with the CIC-the creation of profits to benefit owners and the payment of dividends from those profits are part of the agenda of the L3C, while they are deliberately excluded from the concept of the social business.

L3Cs have been established for a wide array of economic sectors including (Capriccioso et al, 2010): Farming and agriculture, real estate/housing, socially responsible consulting, environmental services, education, healthcare, low-income assistance, construction services, journalism and publishing, financial and legal services and entertainment industry. The L3C structure allows the L3C Missouri Mission Center to provide a wide range of services and incentivize employees to reduce costs. The Mission Center L3C serves a wide range of non-profit and L3C customers. The services offered include accounting and human resources. The Mission Center started with a loan from wealthy supporters and is doing business while securing equity from foundations and individuals.

The 'L3C' is a legal form intended to bridge the gap between for-profit and non-profit functions...[it] combines the financial advantages and governance flexibility of the traditional limited liability company with the social advantages of a non-profit entity. The primary focus of the L3C is not on earning revenue or capital appreciation, but on achieving socially beneficial goals and objectives, with profit as a secondary goal (Capriccioso et al, 2010, p. 33).

33. f) B Corporation

There is another new concept in structuring a social business is the so-called B Corporation.

In the United States, a benefit corporation or Bcorporation is a type of for-profit corporate entity, legislated in 28 U.S. states, that includes positive impact on society and the environment in addition to profit as its legally defined goals. B corps differs from traditional corporations in purpose, accountability, and transparency, but not in taxation.

The purpose of a benefit corporation includes creating general public benefit, which is defined as a material positive impact on society and the environment. A benefit corporation's directors and officers operate the business with the same authority as in a traditional corporation but are required to consider the impact of their decisions not only on shareholders but also on society and the environment. In a traditional corporation shareholders judge the company's financial performance; however, with a B-corporation shareholders judge performance based on how a Year 2015

34. ( E )

corporation's goals benefit society and the environment. Shareholders determine whether the corporation has made a material positive impact. Transparency provisions require benefit corporations to publish annual benefit reports of their social and environmental performance using a comprehensive, credible, independent, and transparent third-party standard. In some states the corporation must also submit the reports to the Secretary of State, although the Secretary of State has no governance over the report's content. Shareholders have a private right of action, called a benefit enforcement proceeding, to enforce the company's mission when the business has failed to pursue or create general public benefit. Disputes about the material positive impact are decided by the courts.

There are around 12 third-party standards that meet the requirements of the legislation. Benefit corporations need not be certified or audited by the third-party standard. Instead, they use third-party standards similarly to how the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) are applied during financial reporting, solely as a rubric a company uses to measure its own performance. In April 2010, Maryland became the first U.S. state to pass benefit corporation legislation. As of October 2014, 28 states have passed legislation allowing for the creation of benefit corporations.

35. VI. Differences of Social Business from Traditional Corporations

Historically, United States corporate law has not been structured or tailored to address the situation of for-profit companies who wish to pursue a social or environmental mission. While corporations generally have the ability to pursue a broad range of activities, corporate decision-making is usually justified in terms of creating long-term shareholder value. A commitment to pursuing a goal other than profit as an end for itself may be viewed in many states as inconsistent with the traditional perspective that a corporation's purpose is to maximize profits for the benefit of its shareholders.

The idea that a corporation has its purpose to maximize financial gain for its shareholders was first articulated in Dodge v. Ford Motor Company in 1919. Over time, through both law and custom, the concept of "shareholder primacy" has come to be widely accepted. This point was recently reaffirmed by the case eBay Domestic Holdings, Inc. v. Newmark, in which the Delaware Chancery Court stated that a non-financial mission that "seeks not to maximize the economic value of a for-profit Delaware corporation for the benefit of its stockholders" is inconsistent with directors' fiduciary duties.

In the ordinary course of business, decisions made by a corporation's directors are generally protected by the business judgment rule, under which courts are reluctant to second-guess operating decisions made by directors. In a takeover or change of control situation; however, courts give less deference to directors' decisions and require that directors obtain the highest price in order to maximize shareholder value in the transaction. Thus a corporation may be unable to maintain its focus on social and environmental factors in a change of control situation because of the pressure to maximize shareholder value. Of course, if a company does change ownership and the result is no longer in adherence to its initially described benefit goals, the sale could be challenged in court.

Mission-driven businesses, impact investors, and social entrepreneurs are constrained by this legal framework, which is not equipped to accommodate forprofit entities whose mission is central to their existence.

Even in states that have passed "constituency" statutes, which permit directors and officers of ordinary corporations to consider non-financial interests when making decisions, legal uncertainties make it difficult for mission-driven businesses to know when they are allowed to consider additional interests. Without clear case law, directors may still fear civil claims if they stray from their fiduciary duties to the owners of the business to maximize profit.

By contrast, benefit corporations expand the fiduciary duty of directors to require them to consider non-financial stakeholders as well as the financial interests of shareholders (Lane, 2014). This gives directors and officers of mission-driven businesses the legal protection to pursue an additional mission and consider additional stakeholders besides profit (Lane, 2012(Lane, , 2013)). The enacting state's benefit corporation statutes are placed within existing state corporation codes so that it applies to benefit corporations in every respect except those explicit provisions unique to the benefit corporation form.

However, in reality, 'B Corporation' carries no special legal status, there is no law defining the B Corporation or specifying any special regulations that apply to it. The idea of the B Corporation was created by an organization called B-Lab, which was founded in June 2006 by a young social entrepreneur named Coen Gilbert. However the B Corporation has no real legal status. Gilbert and his associates at B lab are trying to carve out a place in the economic system for a company that dictates all or part of its profits to social causes. The idea is to formally acknowledge the company's responsibilities to society alongside its economic responsibility to make a profit for investors that benefit society while possibly diminishing profits. Moreover, B-Lab offers a rating system that allows companies to measure their own environmental and social performance by answering a series of survey questions. The results yield a point score, and only companies that achieve a 'passing' score (currently set at 80 out of a possible 200) are eligible to be designed as B Corporations (CSRWire USA, 2010). Unfortunately, California doesn't have laws explicitly addressing that.

Despite this uncertainty, some entrepreneurs have embraced the B corporation idea. As of the end of 2009, there were over two hundred B corporations in the United States. However, a B corporation is not the same as a social business because each B Corporation makes its own decisions about the role of profit. So a B corporation are free to pay dividends to shareholders and to claim a share of the company profits for themselves. It seems this weaken the power of the B corporation concept-perhaps fatally (Yunus 2013).

The existence of the new, alternative forms of business structure -the CIC, the L3C and the B Corporation-reflects the same global situation that social enterprises/social economy organizations are trying to solve humanitarian problems. These new alternative have been devised indicates that many people around the world desire to solve these problems. However, a new regulatory structure essential that could be tailored to the needs of social business should be createdsooner the batter ( Rouf, 2012;Yunus, 2013).

In response to the negative impacts of traditional corporations, a new type of corporation with a formalized purpose that includes generating positive impact for society in its core was needed. The corresponding legislation; however, takes time to develop and be adopted. Independent of the legislative process, a new business certification system was introduced to recognize impact-driven companies: "B Corporations" ("B Corps"). In 2007, a non-profit organization called B Lab was founded to establish and manage the B Corporation certification system which has helped to build a constituency of businesses that is attracting lawmakers' attention. It is a new form of corporations is mobilizing companies toward a sustainable future. Under the banner of 'profitable sustainability' these pioneering companies are actually recovering the 'corporate charter' as a social invention which was originally conceived to bring together the power of private enterprise with the public good." (Karl Ostrom, 2014).

36. a) B Lab

B Lab certifies companies in a similar way that Fair Trade USA certifies Fair Trade Coffee or the U.S Green Building Council certifies leadership in energy and environmental design (LEED) buildings. In this role, B Lab established a standard for responsible and impact-driven business. In addition, B Lab attempts to solve the issue with existing corporate law where shareholder value maximization is the sole fiduciary responsibility of the corporation. Two independent Standards Advisory Councils oversee B Lab's certification standards, including the global impact investing rating system (GIIRS) for impact investors. B Lab is backed by a diverse set of funders, including the Rockefeller Foundation, USAID, and a variety of corporations, private foundations and individuals. There are currently about 20 employees across four different locations in the US. B Lab's website is www.bcorporation.net.

37. b) Grameen Social Business Initiatives

Muhammed Yunus considered Grameen as the seed of social business in Bangladesh that established in 1970s. Grameen bank and its other sister organizations are following the principles of social business for solving the problems of employment and income, hunger, malnutrition, healthcare, agriculture, housing, hygiene, education, environment, energy, communication, transportation etc. Grameen sister organizations are running as social businesses in Bangladesh (Yunus, 2014).

38. c) Grameen Youth Entrepreneur Loan

Grameen Bank has introduced entrepreneurial loan for those who have got higher education loan, and who are enterprising, industrious, enthusiastic and hardworking. It was introduced in Grameen Bank in 2008. This is an opportunity created for the children of GB families who want to be self-employed for income earning. This is to encourage them to deviate from the Revenue-Generating Social and Economic Mission-Entwined Praxis of Organizations Grameen social business can play a very important role in solving the financial crisis, the food crisis, and the environment crisis. Furthermore, it can provide the most effective institutional mechanism for resolving poverty, homelessness, hunger and ill health (Grameen Dialogue, 2014). Social business can address all the problems left behind by the profit-making businesses and at the same time it can reduce the excesses of the profit-making businesses. Muhammad Yunus (2013) asserts that social business must be an essential part of the growth formula because it benefits the mass of people who would otherwise be disengaged. And when people are energized, so is the economy. Through access to credit, improved health services, better nutrition, high-quality education, and modern information technology, poor people will become more productive. They will earn more, send more, and save more-to the benefit of everyone, rich and poor alike (Ibid, 2013).

B Lab is a non-profit organization with the mission of using the power of business to address the world's most pressing challenges. In its goal of using business as a force for good, B Lab focuses on three initiatives: Building a community of Certified B Corporations so one can tell the difference between "good companies" and just good marketing; accelerating the growth of the impact investing asset class through use of B Lab's Global Investing Impact Rating System (GIIRS) Ratings & Analytics by institutional investors; and promoting legislation creating a new corporate form that meets higher standards of purpose, accountability and transparency.

Year 2015

39. ( E )

conventional way of seeking job after completion of higher education but going for creating job for themselves as well as for others. Those who chose this path and took loans from Grameen Bank for business were called Nobin Udokta (NU) or New Entrepreneurs.

40. d) Nobin Udyokta (New Entrepreneur) e) Grameen Social Business Design Lab

Muhammad Yunus mobilizes Grameen sister organizations to be involved in implementing Nobin Udoktas Loans. Grameen Social Business Design Lab is a platform for Nabin Udyokta and Grameen sister organizations to bring the entrepreneurs to present their social business designs in front of a group of experienced business executives and social activists, to seek their advice. This platform encourages people to two things, it encourages people to come up with social business ideas and develop this platform as a sounding board for getting the concept of social business more business-ready through its application in concrete situation. Yunus Centre organized the first Design Lab in January, 2013. Now Grameen Design Lab conduct workshop in every month. Nobin Udyoktas present their business plans at the Grameen Design Lab Workshop with the help of Grameen sister organizations, social business angel investors. Nobin Udyoktas receive loans from Grameen sister organizations after approval the loan in the Grameen Design Lab workshop house. Now implementation structure of Grameen social business lab has built, the speed of expansion spread quickly across Bangladesh. For example, by the end of March, 2015, 780 NUs presented their business plans in the design labs and 512 loans were disbursed. Many internees from across the world, social business academicians, researchers, executives, philanthropies are attending the Design lab workshops. The author attended many Grameen Design Lab workshops in 2014-2015 and has learned about the practical process of the preparing Nabin Udyoktas loan proposals, business plans, review of the business plans, and approval of the business plans and loan disbursements. In the business plan, NUs need to address the following social objective questions:

? What is my social objective e: Whom do I expect to help with my social business? ? What social benefits do I intend to provide? ? How will the intended beneficiaries of my business participate in planning and shaping the business? ? How will the impact of my social business be measured? ? What social goals do hope to achieve in my six months? In my first year? In my first three years? ? If my social business is successful, how can it be replicated or expanded? ? Are there additional social benefits that can be added to the package of offerings I will create?

f) From Grammen Micro-credit to Grameen Equity Grameen sister organization investors provided equity investments with the Nabin Udokta individually.

41. Revenue-Generating Social and Economic Mission-Entwined Praxis of Organizations

For educated second generation of GB borrowers and for other young people, GB sister organizations have started campaigning to redirect their mind from traditional path to hunting for jobs to creating jobs for themselves and others (Yunus, 2013) through entrepreneurship. GB called those who chose that path and took loans from Grameen Bank or Grameen sister organizations as Nobin Udokta (NU) or "New Entrepreneurs". It is targeted to the youth in Bangladesh who wants to use their creative power to become entrepreneur not only to generate their own employment but also to create employment opportunities for others. The social business idea started getting root in Bangladesh.

By Mid October 2014, 380 NU projects have already been approved by the participating grameen sister organizations for equity investment of TK. 8, 45, 57000 (US$1, 09 million). Among the NUs about 7% are female and 93% are male entrepreneurs. Their age varies from 18-35 years with most of them coming from 20-30 years of age (Grameen Dialogue 93, pp. 6). The NUs are engaged in different kinds of business activities including telecom, IT, repairing, manufacturing engineering, handicrafts, Livestock, Live Stock feed production, drug store, fish and agro-farming, trading, nursery, whole sale and retail business. Their (NUs) business insight, continuous thinking, information gathering, networking, skill development, keeping commitments and risk taking attitude are all important for them to become successful entrepreneurs. There are funds also available for social business from Yunus Social Business Fund (YSBF) in Haiti, Colombia, Albania, Tunisia, Uganda, India, Mexico, Brazil and Grameen Credit Agrocole Social Business Fund in France (Grameen Dialogue, 93). Grameen investors shall be monitoring the performance of the managers/managing partners, but Grameen investors shall not get involved in the actual running of the business. As the business makes profit, the Grameen investors receive their dividend. When Grammen investors have received enough dividends to equal to the amount of equity Grammen investors have invested, Grameen investors stop taking further dividend. It is time for investors to move to on to the next investment with the money they got back. But grameen investors' objectives shall not be achieved until Grameen establishes the entrepreneurs as the owner, because their intentions were to transform a job-seeker into a job-giver (Yunus, 2013).

42. Grameen Social Business

Grameen social business items in Bangladesh are setup dental clinic, nursing center, community information center, compost/worm production, door mate produce from garment wastage, fruits plant nursery, setup KG school and community school, community adult learning center, irrigation project, fish culture, poultry and dairy farming, mini garments industries, fashion design and tailoring, bee keeping culture, installing solar home system, biogas plant, buying rice husking machine, IT center, computer training center, manufacturing paper products from recycling papers, pottery business, hide and leather business, old clothing business, winter clothing business, electronics business, repairing shoes, electronic products TV, Cell Phone, Radio, Computer, IPod, repairing auto mobile engines, house repairing, manufacturing bamboo products, toys, makings mosquito nets, oil processing plant, cottage industries, handmade bags, manufacturing pads, carom board, poultry feed, Ayabade medicine, milk processing plant, cult making, rings making, restaurant, etc. By September, 2013, Yunus Center developed basic methodology, reporting formats, identification and assessment procedures, etc. Grameen sister organizations brought the NU projects to the Design Lab for getting critical assessment from a group of experienced professionals. Now more Grameen companies (Grameen Telecom Trust, Grameen Bybosha Bikash, Grameen Shakti) have in initiated their own NU programs.

43. Revenue-Generating Social and Economic Mission-Entwined Praxis of Organizations

According to social business guidelines, investor can sell his shares at the market value, but he has to reinvest the additional money he receives beyond the face value, into another social business, or in the same social business. Investor can not enjoy additional value created by his investment (Yunus, 2013). In the NU programme, Grameen made an easy rule. In selling the shares of a NU business, the investor will take an amount equivalent to the original fixed sum of 20% over it. Grameen call the additional amount "share transfer fee". This fixed amount of 20% is only a small fee for covering all these services over a period of several years.

Nabin Udokta receives percentage of business investments equity from Grameen with 20 percent business transfer fee through the years of the agreed agreement. Grameen investors monitor the business and collect the investments equity instalment. Grameen Investors does not take any profit from their investments, except for getting their investments money back. The NU is responsible for paying back whatever money they received as equity within an agreed period. Grameen offers this exciting opportunity for any entrepreneur in Banglaedsh. The entrepreneur may have some or no shares in his business. He can be the managing partner or a paid manager of the business he owned Grameen Social Business concept uses some terminologies that are different from Grameen classical loan program.

(Yunus 2013).

Year 2015

44. ( E ) g) Grameen Screening Process of Selecting NUs in Bangladesh

Social Entrepreneurship formal discussion in small groups of 4 or 5 takes place to let them get to know each other. Once a sizable number (say 30-50) of young men or women have been contacted the village staff will organize an orientation and identification camp in a village (Yunus, 2014). Experienced camp leaders will attend the camp to carry out the identification and confidence building process. Participants learn the rules and procedures of NU programme, ask questions to get a clear picture of the programme. They assess each other's business plans, strength of their business will. At the end of an intensive get-to know-your-entrepreneur exercise, camp leaders make a short list of the participants who have impressed them as entrepreneurs likely (Grameen Dialogue 90).

Entrepreneurs selected are invited to Dhaka where they'll give final shape to their business plans and give them a professional appearance with the help of trained staff of the investors. Project summaries are prepared in English for a five minute presentations at the Design Lab where the entrepreneur has to defend his project. Participants give some good advice and flag some issues to help better implementation (Yunus, 2013). In rare cases an entrepreneur is asked to modify his plan to make further improvement and present it to the next Lab. Once the project is approved, handholding process for implementation begins. Investor and the entrepreneur now go through a process of bonding together for a successful journey ahead. All regulatory issues are threshed out, necessary documentation is completed. Once monitoring and accounting training are completed, disbursement day (D-day) funds are released and business starts running Grameen Dialogue 93. Grameen Communication, a Grameen software company, has developed an accounting and monitoring software to collect MIS and accounting information from every NU business on a daily, weekly and monthly basis. Daily figures are sent via text messages. All information accumulates at the central server, which produces reports for each investor on daily, weekly, monthly or for any other period as the investor would like to have.

45. VII. Urgently need Legal Structures of Social Business

Legal and regulatory systems do not currently provide a place for social business. Profit-maximizing companies and traditional non-profit organizations (foundations, charities, and NGOs) are recognized institutions covered by specific rules regarding organizational structure, governance and decision making principles, tax treatment, information disclosure and transparency, and so on. But social business is not yet a recognized business category. This needs to change. The sooner there is a defined legal and regulatory structure for social business-preferably one with consistent rules in countries around the world-the easier it will be for entrepreneurs and corporations to create a multitude of social businesses to tackle the human problems that are plaguing society (Yunus 2014). Muhammad Yunus thinks (2013) the best option today is to organize one's social business under the traditional structure of a for-profit business. The for-profit legal framework/structure is used for all of Grameen's social business. The legal system gives the for-profit company great freedom and flexibility to experiment with its business model. Thus, a social business organized as a for-profit company must be just as financially efficient as any other for-profit company, since it doesn't benefit from any tax breaks (Yunus, 2014).

In the future, governments can and should create a separate law for social business, defining it adequately for regulatory purposes, and indicating the responsibilities and obligations of the stakeholders. The law should lay down the rules and procedures a social business must follow in order to switch to a profitmaximizing company. At the same time, Lawyers should amend the existing company law to include the rules and procedures under which a profit-maximizing company can switch to a social business company. Under US law, foundations can invest in for-profit companies only if the investment qualifies as a 'program-related investment' (PRI). Unfortunately, the rules defining PRIs are complicated, and violating them can lead to serious tax problems for the foundation. As a result, many foundations shy away from such investments(Grameeen Dialogue 93).

According to M. Yunus (2014) there are serious limitations to using the non-profit structure for social business. Perhaps the most significant is the strict legal and regulatory scrutiny that non-profits often experience. Robert A. Wexler (2009 in Yunus 2013), an American attorney in his article 'Effective Social-Enterprise-A menu of Legal Structures' comments about the difficulty of winning tax-exempt, non-profit status for such organizations in the United States. However, Yunus definition of social business, there's no good fit with the noon-profit structure. The most important reason for not using the non-profit legal structure for creating a social Revenue-Generating Social and Economic Mission-Entwined Praxis of Organizations Grameen sister organizations have village staff to work with the Nabin Udyoktas (new entrepreneurs), is responsible for identification, screenings of the potential entrepreneurs to help them develop their business plans, and prepare the NUs to make presentation of their plans to the participants of the Gramen Design Lab workshops. The whole process starts with the home visit of the potential entrepreneur and getting to know him and his family in all details, capture his dreams and fears, and try to build confidence in him (Grameen Dialogue 91-92). business is that a non-profit is not owned by anyone; it can't issue shares. A social business has one or more owners, can issue shares, and can buy and sell shares, just like any for-profit company.

46. Global Journal of Human Social Science