1. Introduction

an is the ultimate evolution of nature. As a social and physical creature he is governed by invariable laws. These laws are the necessary relations arising from the nature of things (Montesquieu, 1748). With the development of human society social laws emerged as a base to maintain social serenity. Gradual development of society filled a thirst for development in humankind. This desire whenever and wherever failed, generated frustration, depression and aggression. Lopsided economic development further strengthened these feeling by giving birth to poverty, unemployment and deprivation. These situations in combined ultimately produced crime. Among all the crime categories homicide is the severe most where society loses all the ethical bounds. It may be defined as "unlawful death purposefully inflicted on a person by another person" (UNODC, 2014 : 21).

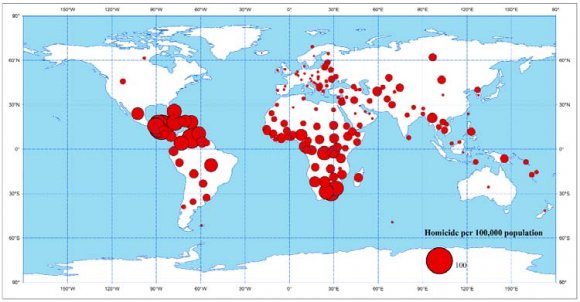

Homicide caused the deaths of almost half a million people (437,000) across the world in 2012. More than a third of those (36 per cent) occurred in the Americas, 31 per cent in Africa and 28 per cent in Asia, while Europe (5 per cent) and Oceania (0.3 per cent) accounted for the lowest shares of homicide at the regional level (UNODC, 2014).

The global average homicide rate stands at 6.2 per 100,000 population, but Southern Africa and Central America have rates over four times higher than that (above 24 victims per 100,000 population), making them the sub-regions with the highest homicide rates on record, followed by South America, Middle Africa and the Caribbean (between 16 and 23 homicides per 100,000 population). Meanwhile, with rates some five times lower than the global average, Eastern Asia, Southern Europe and Western Europe are the subregions with the lowest homicide levels. Interestingly most of the homicide is situated between 30° North to 30° South latitudes, which is the warmest region on the earth (Fig. 1).

Based on: UNODC World crime record, 2014 Crimes result from the interaction between individuals and environment, and the majority of the literature that has investigated the relationship between weather and homicide support the theory that weather does affect murder occurrences (Cohn, 1990). The literature pertaining to the effect of weather element on behaviour reveals two major biological theories. The first theory considers weather changes or extremes to be stresses. The theory states that if a person is highly stressed, or more sensitive to stressors, weather change may exhibit behavioural or mood changes to him. The second theory considers weather as a stimulus to the human organism which can have both physiological and psychological effects (Moos 1976). Researchers have found that weather is the production function for crime (Cohn, 1990;Agnew, 2012). Becker (1968) and Jacob et al. (2007) considered weather conditions as an input that affect the probability of successfully completing a crime and escaping undetected afterward.

Scientists have adopted different approaches and types of data sets to draw their results. While some studies have focused on measuring the short-term relationship between weather and crime using hourly, daily, or weekly microdata (Horrocks and (Anderson et al., 1997, Rotton andCohn, 2003). While micro studies have noticed accountable influence of weather elements on homicide rate, the studies analysing bigger regions have found mixed results, possibly due to the lack of temporal and geographic resolution in their homicide and weather data. Among all the climatic elements, temperature and precipitation are the most important determinants for weather conditions. And, therefore, variability pattern of these two elements may define the nature and degree of association between weather and homicide rate. On the basis of cost and benefit analysis, James Horrocks and Andrea Menclova (2011) found evidence that temperature and precipitation supported violent crimes. Michael and Zumpe (1983a, l983b) found a positive relationships between the annual mean temperature and annual mean homicide rate. DeFronzo (1984), also found positive association between year-total homicide data and the number of 'Hot Days' in their study. John Cotton (1986) suggest that aggressive behaviour increases above 90°F. An analysis by Harries and Standler (1988) suggests that there is no curvilinear effect between temperature and aggression, even during conditions of extreme heat. On the other hand Jacob et al. (2007) found that short term weather changes impacts weekly or daily rates of criminal activity but in the long run the correlation is not linear.

A series of experiments on the influence of high ambient temperature on aggressive behaviour by using two temperature conditions ('hot' being approximately 93°F and 'cool' being approximately 73°F) and two arousal conditions established a curvilinear relationship between aggression and heat (Baron 1972; Baron and Lawton 1972; Baron andBell 1975, 1976;Bell and Baron, 1976). These experiments noted that aggressive behaviour increases with heat up to about 85°F, and then decreases. However, Anderson and Anderson (1984) proposed that the curvilinear effect may be an experimental artefact, because the temperature manipulations were extremely obvious to the subjects. Bell, Fisher, and Loomis (1978) concluded that extremely high ambient temperatures, especially when combined with other sources of irritation or discomfort, may become so debilitating that aggression is no longer facilitated and may well be reduced' (Bell, Fisher, and Loomis 1978). On the other hand, by using negative feedback technique Bovanowsky et al. (1981) found that aggression increased with heat. Feldman and Jarmon (1979) found no significant correlations between ambient temperature and homicide. A ten year period trend analysis by Perry and Simpson (1987) recorded no significant relationship between the monthly homicide rate and the monthly minimum temperature. In his study Cohn (1990) could not establish a significant relationship between heat (temperature) and homicide rate, however he concluded that heat does affect crime in the areas of aggression and violence.

The review reveals that while the daily influence of heat on homicide is doubtful, there is evidence of long-term association of homicides with hightemperatures. However, this association could be mediated by a variety of cultural, regional, and historical factors.

The relationship between rain and crime appears to vary with the type of crime examined. While assault and other crimes show some notable association with precipitation, homicide does not associate very well. Feldman and Jarmon (1979) examined the association between rainfall and crime on a day-to-day basis and did not find any significant correlation between precipitation and homicide rate. In examining the relationship between rainfall and crime, DeFronzo (1979) considered the number of days on which amount of precipitation exceeded 0.25 mm. while in his study Perry and Simpson (1987) analysed monthly amounts of precipitation and month-wise crime rate. Like Feld and Jarmon, these two studies too could not establish notable relationship between precipitation and homicide rate. In his study of homicide and aggravated assaults, Pokorny (1965) found the similar results that homicide is not significantly related to rainfall.

The results of these studies show both negative and positive outcomes, and they commonly suggest that while temperature (heat) have conflicting influences on homicide rate, rainfall does not seem to be a good predictor for the same.

Besides these researches suggesting influence of physical environment on homicide, there are number of studies explaining crime pattern on the basis of social interactions that occur during day-to-day life (Glaeser, Sacerdote, and Scheinkman, 1996; Rotton and Cohn, 2003). However, these studies too acknowledge the role of physical environment and believe that weather conditions that foster social interactions are likely to increase crime rates. World is passing through a phase of industrialisation and rapid urbanisation and these two have been regarded as precursors in bringing socioeconomic development. However, many researchers consider industrialization and urbanization as an underlying causes of crime. Shaw & McKay (1969) were of the view that "due to constant influence of exogenous forces such as industrial invasion and migration, the process of industrialization and urbanization promotes crime". These exogenous forces disturb the traditional norms and values of the community, and continuous invasions of "foreign" cultures, and sprawling large urban settings, prevents the community from establishing shared norms and values. Crime rates are expected to be relatively low in societies characterized by a homogeneous population and simple technological development because social norms are relatively strong, unambiguous, and binding. In societies characterized by heterogeneous populations, perhaps as a result of rapid socioeconomic change (i.e., industrialization and urbanization), individuals are less likely to accept grouporiented discipline over personal desires due to confusion over norms and values (Tsushima, 1996).

It is said that human behaviour can be largely predicted by his socio-economic environment (Bonger, 1916: 75-76), and economic structure has a considerable impact on human activities such as crime, especially in terms of income level or poverty, economic inequality, and economic opportunity. Quetelet (1984) opined that crime is especially significant in areas with rapid social or economic change, rather than in areas where people are poor but are able to satisfy their basic needs. Poverty increases the probability of peoples` involvement in criminal activities. Philips (1991) says that economic independence for the poor is the single most crucial element in any plan to fight crime. Blau and Blau (1982) reports that economic inequality is positively associated with high rates of violent crime. In his study Bailey (1984) and Williams (1984) found that poverty is positively (insignificantly) associated with homicide rates, while Messner (1982) noticed that poverty has a negative (although insignificant) impact on homicide rate. Aronson (1988) argues that poverty leads frustration, which further leads to aggression. Aronson further stressed that "frustration is not simply the result of deprivation; it is the result of relative deprivation" (1988: 212-13). And, therefore, a society with the high level of economic inequality will have high crime rates (Bayley, 1991;Ladbrook, 1988;Tanioka & Glazer, 1991, Tsushima, 1996, Hartnagel & Lee, 1990).

Unemployment is also considered to be a major factor in incidence of crime. The unemployed people are more likely to be exposed to the lure of criminal subcultures because of their lack of involvement in conventional activities and close personal relationships with non-family members (Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990; Kelvin & Jarret 1985: 53). Researchers have found mixed results on unemployment-crime association. Danziger (1976) and Jacob (1981) noticed a positive relationship between unemployment rates and homicide, while Spector (1975) found no significant relationship between unemployment rates and murder rate. On the other hand Crutchfield et al. (1982), and Kennedy et al. (1991) recorded a negative relationship between unemployment rates and homicide.

This study addresses mainly the association between atmospheric warming and homicides by taking India as a case. Meanwhile it also attempts to understand different underlying factors responsible for the murder incidences.

II.

2. Data Sources and Methodology

Temperature is one of the most important determinant of weather conditions and most of the studies examining relationship between climate and crime are based on the variability pattern of temperature. Present study is also confined to this climatic factor to analyse the association between climate and homicide rate. The study is based on the month-wise data for 13 years period (2001-2013) at state and district level in India. The temperature data were obtained from India Meteorological Department, while district level monthly homicide rates were extracted from crime census records published by National Crime Record Bureau. World level crime pattern is based on the data of United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. To map poverty, Human Development Report 2013, was used while population figures are based on Census of India, 2011.

Homicides occur more infrequently than other violent crimes, and this may, thus, seriously reduce the effectivity of the statistical tests employed. Therefore, the study examines the nature and level of association between weather and crime by using maps and graphs, however simple statistical techniques have also been employed.

3. III.

4. Results and Findings

Increased crime rates play a decisive role in hindering the growth of a nation as a unit, especially in the case of developing countries like India. India has recorded 33201 murder (3 per lakh population), 33707 rape (3 per lakh population), 65461 kidnapping & abduction (5per lakh population), 72126 riots (6 per lakh population), and 2647722 IPC crime incidences (219 per lakh population) in 2013 (NRBC, 2013).

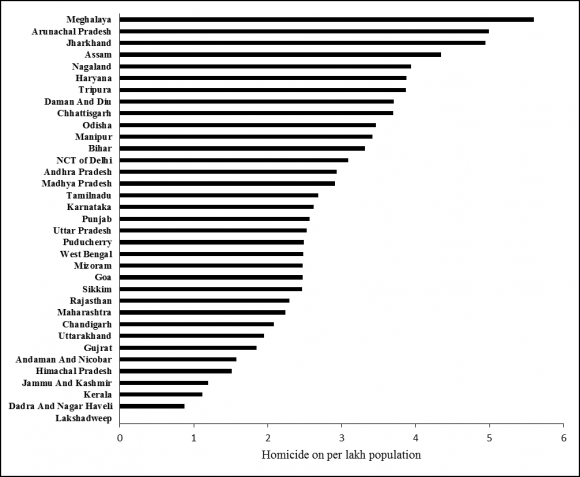

Kerala State that tops in many development indicators, has the highest rate of crimes under the Indian Penal Code in India (NRBC, 2013). (Fig. 2). At 455.8 per lakh population, the crime figures for Kerala is more than double of the national average. Nagaland, according to the report, has the lowest crime rate that is only a tenth of that in Kerala. Among cities, Kochi reports 817.9 incidents of IPC crimes for every lakh population, the highest in the country. Indore comes second with 762.6 incidents. Looking at the pattern of homicide at district level, Nadia district of west Bengal has recorded highest homicide cases (517). Nadia has also registered highest number of total incidences of IPC Crimes (80184). However comparing on absolute numbers does not seems very convincing because every state and district have different population size. To compare in real terms the study measures homicide rates on per lakh population. At per lakh population base, Dibang Valley district of Arunachal Pradesh records the highest number of homicides on per lakh population.

5. Source: National Crime Record Bureau of India

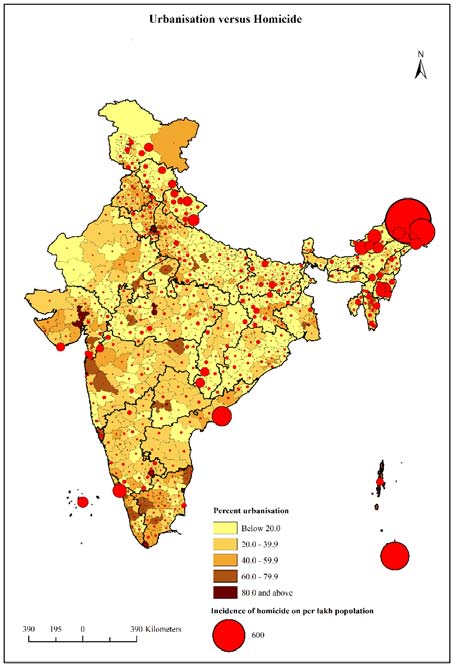

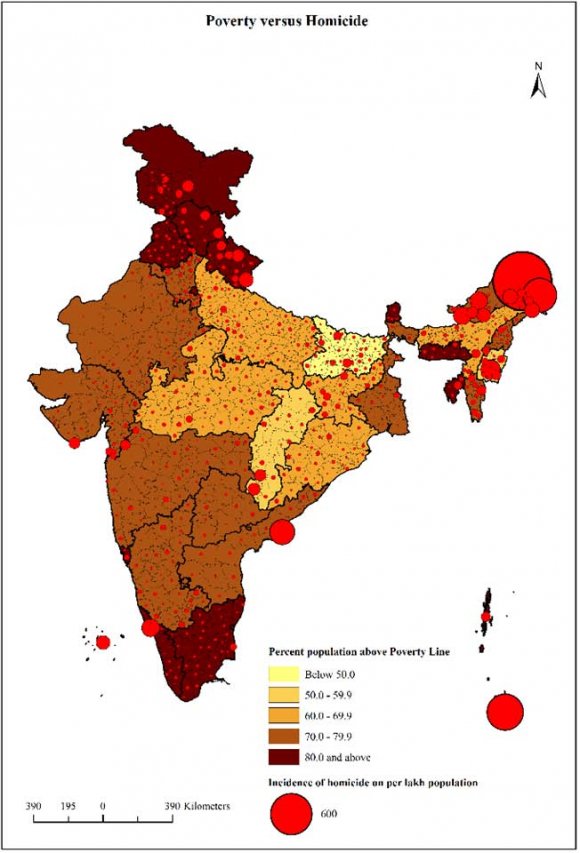

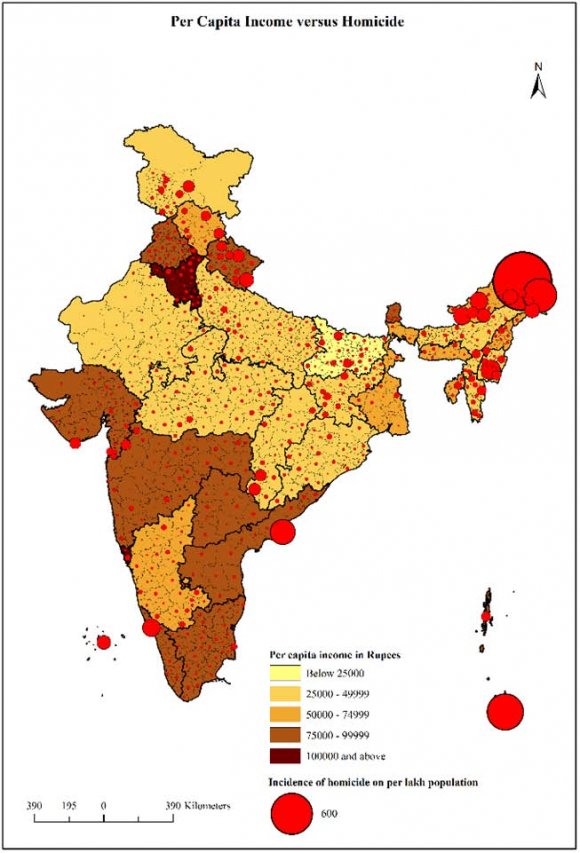

The urbanisation profile of India suggests that homicide is not significantly associated with the level of urbanisation. The North-Eastern districts of the country and especially the districts of boundary state-Arunachal Pradesh which are poorly urbanised, record the maximum homicide per year (Fig. 3). In general the less urbanised Himalayan states of India-Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh, Tripura, Nagaland, Manipur and Mizoram have recorded high homicide rates. However, some highly urbanised coastal districts also have registered the high homicide rate. Table 1 shows some districts of India those have recorded the highest homicide rate and respective level of urbanisation there. It is clear that urbanisation and homicide are not very well correlated and the data of the table 1 produces very insignificant and negative correlation (-0.06) between homicide and urbanisation. Studies suggest that socio-economic state influence the human behaviour and homicide rate significantly (Bonger, 1916;Quetelet, 1984;Philips, 1991;Blau and Blau, 1982;Bailey, 1984;Williams, 1984;Messner, 1982). Undoubtedly income and poverty are the two most important determinants of wellbeing but here in case of India, results suggest that regions above poverty line are also the areas having more homicide incidences with some exceptions like some poverty stricken districts of Bihar (Sheikhpura, Sheohar and Jehanabad) and Chhattisgarh (Bijapur and Narayanpur) have registered high homicide rates (Fig. 4).

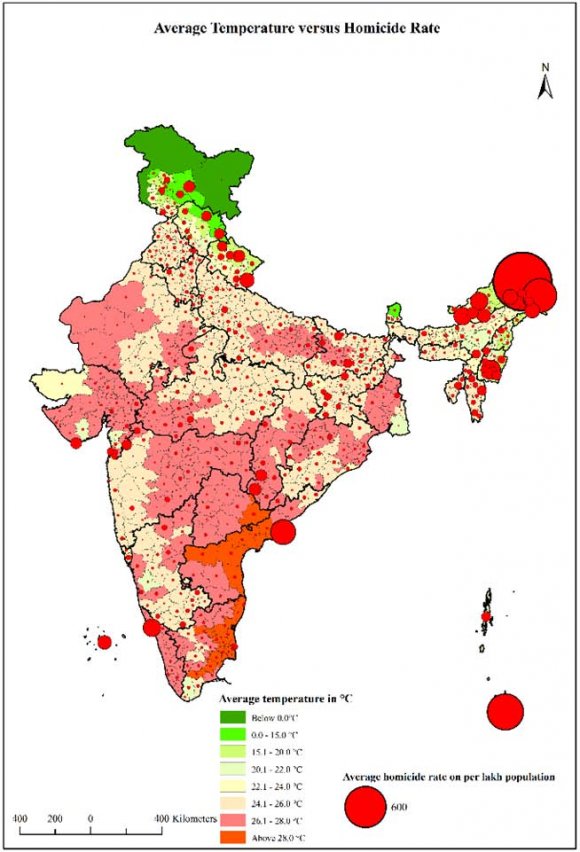

Per capita income has not shown any significant relationship with homicide rate (Fig. 5). States like Haryana and Delhi which have recorded the highest per capita income are not the regions of high murder rates. While on the other hand almost all the districts of Uttarakhand and some districts of Telangana, Kerala, Gujrat and Maharashta have shown a significant and positive association between murder and income. Apart from socio-economic factors, physical elements seems having more striking connection with homicide pattern. The analysis of temperature-homicide association on the basis of average temperature data for the study period of 2001-2013 support the hypothesis that temperature does affect homicide rate, although exceptions are there. Average annual temperature over India varies between -1.86°C (Leh-Ladakh in Jammu & Kashmir) to 26°C (Kraikal in Puducherry) and while low temperature zones of Jammu & Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand and Arunachal Pradesh registered the maximum homicide, some high temperature regions of Kerala, Telangana, Maharashtra, Gujrat and Chhattisgarh states too have recorded high homicide rates (Fig. 6). However, figure 7 presents some convincing explanation of temperaturehomicide association by comparing warming and homicide trends. Evidently all the regions which have witnessed significant warming during the analysis period of 13 years (2001-2013), are also the areas of high homicide rates.

IV.

6. Conclusion

Results suggest that social parameters like urbanisation, poverty and per capita income do not correlate very well with homicide trends. On the other hand regions of harsh climatic conditions-desert areas (districts of Rajasthan) and mountainous landscapes (districts of Jammu & Kashmir, Uttarakhand, Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Kerala) have a significant covariance with homicide rate. Districts of almost plain topography and mild climatic condition did not show any significant relationship between homicide and temperature trends. The regions which have shown the warming trend during the past decade have recorded the increasing murder incidences. Thus, while ambient temperature conditions, and heterogeneous landscape (physical as well as social) seems catalytic to increase the murder rates, warming trend also has a great bearing on homicide incidences.

| District | State | Murder per | Urbanisation |

| lakh | in per cent | ||

| population | |||

| Dibang | Arunachal | 50 | 29.79 |

| Valley | Pradesh | ||

| Bijapur | Karnataka | 27 | 11.60 |

| Nicobar | Andaman and | 22 | 0.0 |

| Nicobar | |||

| Khunti | Jharkhand | 20 | 8.46 |

| Gumla | Jharkhand | 19 | 6.35 |

| Bijapur | Chhattisgarh | 18 | 11.60 |

| Kokrajhar Assam | 12 | 6.19 | |

| East | Arunachal | 11 | 23.32 |

| Kameng | Pradesh | ||

| Jaintia | Meghalaya | 11 | 7.20 |

| Hills | |||

| Simdega | Jharkhand | 11 | 7.16 |

| Yanam | Puducherry | 11 | 100 |