1. I. Introduction

hen we talk about globalisation, we cannot exclude that the world today is undergoing unprecedented global changes in every dimension of human activity and interaction. This is the subject of this paper. It is imperative to note that some of the globalisation changes are new opportunities and others are challenges. Poverty, unemployment, women exploitation, lack of democracy and human rights, corruption, illiteracy, hunger, disease, over population, inequality and exclusion (to name but a few) have not been alleviated by recent advances in science and technology, nor by economic and financial globalisation and modernisation. In fact, social problems are rapidly worsening and are indeed aggravated by the effects of globalisation and modern technology (Delors, 1996). Added to these are new development-related dangers, relating to massive demographic shifts, and urbanisation, such as severe environmental degradation, climate change and loss of biodiversity, which affect large portions of developing countries. Then there are complexities arising from the dramatic growth of multimedia, information and communication technologies and rapid advances in science, biogenetics and technology, which have the potential to bring progress, social and economic well-being, but in practice give rise to new inequalities, a growing digital divide, ethical dilemmas, threats to governance and cultural standardisation (Annan, 2003;Faure, 1972). The failure for cultural standardisation may be due to the racially diverse regions of the world, containing a rich tapestry of languages, religions, cultures, ethnicities and heritage (multiculturalism) which might breed conflicts which might lead to underdevelopment especially in the developing world (UNESCO, 1998). Therefore, in a situation of this nature, what could be done in order to keep our society out of such human degrading circumstances?

2. The problem

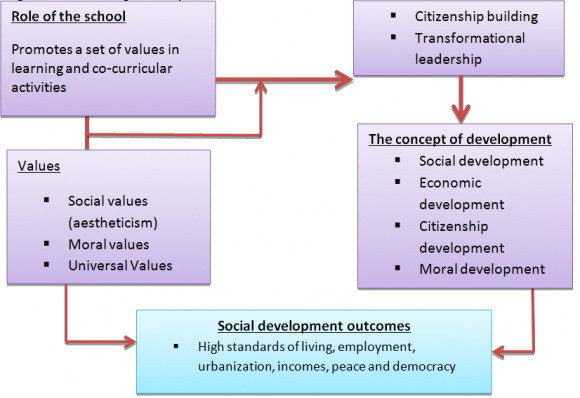

Many scholars have written about the political, social and economic role in mitigating under development conditions of the kind (Tuyizire, 2001; UNESCO, 1998). Also scholars have indicated the role of education in social development, but the problematic case is that no study has attempted to show roles of schools in tackling the development challenges through values-integration in learning, yet as Sekiwu (2013) noted, values are key life principles. Values are supportive of positive social change, innovative development, and citizenship building.The problem for this research is twofold: firstly, to clearly demonstrate, with research data, that failure for education to address the challenges of development today poses a great threat to the Ugandan educational system and to the Ugandan society. Secondly, to show that the situation can be remedied through the strengthening of the valuebased component in the educational system, which would require examining the roles of schools in integrating values education in order to contribute to a strong linkage between values, education and development. This study thus attempts to bridge the gap by examining the role of the school in integrating values for social development. (Batson & Thompson, 2001). Part of the literature describes values at the individual-level as yardsticks for determining individual progress, and providing the desired individual end-goals. At an organizational level, some researchers tend to assume that values are modes of behaviour that propel change in an organization (Searing, 2009:433). At a societallevel, values could be defined as elements of "conformity" to the established order. People must conform to norms and customs, of particular societies, in order to ensure cohesiveness (Njoroge & Bennaars, 2000). At a universal-level, scholars at times define values to mean human ethical standards. In other words, universal-level values must delineate principles of objective ethical goodness (Putterman, 2000:79). For example, it is of a universal concern that every human being possesses objective moral ethics (Du Preez & Roux, 2010:78).

Self-directional values are values that touch an individual independent of others (Jumsai, 2005:44). They are basically personal values that develop the selfconcept. A critical understanding of the self-directional values blends with an understanding of human behavioural theory, specifically with Sigmund Freud's concept of character and Erich Fromm's Psychoanalytic Theory (Ryan & Riordan, 2000:454). Values also classified as moral. Moral values are principles to which a person's character is judged as being good or bad (Fisher, 2002:99). Examples of these moral values are love, respect, tolerance, and dignity of a human being (Ozolin, 2010:415;Ryan & Ciavarella, 2002:179).

The 'spiritual values' viewpoint dictates that human behaviour owes its allegiance to the theological standpoint. In order to ensure a morally upright person, the relationship between God and man must actively interplay (Feldman, 2003:477). This spiritual view is partly explained in Saint Augustine's doctrine of the political state. The state is described as a family defined by the relationship between God and man (Mugagga, 2007:25;Tiel, 2005:18-26). In this state, the Divine nature of God is the Centre of what is of value, and man is the inferior being that must respect the Divine will (Genza, 2008:45;Ssebwuufu, 2006:67;Ssemusu, 2003:37). Therefore God and human values are connected. Without believing in God, Saint Augustine argues, human goodness cannot prevail (Brennan, & Modras, 2000:122). Values are also universal. Values at the universal level are assumed to be those at the apex of human society. These are values for every society, nation and humanity (Morrison, 2000:210).

Based on the above analysis of literature, values could be defined as the desired moral and secular principles of human life developed from childhood through adulthood and categorized as individual, group and universal elements that facilitate human goal achievement in personal, collective and transient in some ways.

3. b) Understanding social development

The concept of social development has distinct features which are an attempt to harmonize social policies with measures designed to promote social, economic, cultural and political development. It is an approach for promoting human social welfare. The term "development" connotes a process for economic change brought about by industrialization, urbanization, the adoption of modern life style, and new attitudes. Further, it has a welfare connotation which suggests that development enhances people's incomes and improves their educational levels, housing conditions and health status. However, the concept of development is most frequently associated with economic change, and social welfare (Midgley, 2006). But critics (Fukuyama, 2006;Midgley, 2006), with justification, question the pace of development in developing countries. They note that grinding poverty still sweep majority of the communities in Africa, Asia and Latin America. Housing conditions are atrocious, and the spectrum of starvation still haunts many millions of rural dwellers, homeless children such as in northern Uganda after the war with Joseph Kony. Many will also point out that even among the prosperous industrial nations; homelessness, inner city decay, needs and neglect remain endemic. Experiences of these exist in Black South Africa among the historically marginalized communities (Pauw, Oosthuizen & Van der Westhuizen, 2006). Those who believe that there has been little social progress will note that cataclysmic wars have caused the death of many millions of human beings, for example recently during the ousting of Colonel Muamar Gadhafi in Libya. The same applies in Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Israel, Egypt and Palestine. The holocaust, the Rwanda genocide and the ongoing racial and ethnic hatreds, which perpetrate violence and brutality, plus the widespread subjugation of women all account for elements that social development is still far from our planet (Fukuyama, 2006).

4. c) Tackling the development challenge: The place and role of schools

In a troubled world experiencing such development problems like military conflict, violence, and risks of dehumanisation amidst multiculturalism and regionalisation; the role of schools cannot be underestimated (Adelani, 2008). Schools work not only to promote peace building but also education for economic development. This paradigm shift helps in producing socially responsible products to participate in social-economic transformation (Association for Living Values Education International, 2010). Education must promote values for lifelong learning, peace and citizenship building, social justice education hence fostering sustainable development (Sekiwu, 2013;Delors, 1996). For instance, aknowledge based economy is one where knowledge is created, acquired, transmitted and used effectively by enterprises, organizations, individuals, civil society and all the communities (World Bank, 2006). A study by Midgley (1995) paints that education and economic growth in emerging economies has found that investment in education is more beneficial in enhancing social development. Because of the internationally renowned role of education in development, the Ugandan government introduced a series of stabilisation programmes in the 1980s and 1990s as a quest for macro-economic development.

One of these stabilisation policies was the universalization of education (Primary and Secondary education), that led to the introduction of Universal Primary Education (UPE) which increased school enrolment in government aided primary schools from 2.9 million in 1996 to 6.8 million in 2001, up to 7.3 million in 2006 (Ministry of Education and Sports, 2007). This influx led to the increase in access to secondary education calling for responsible leadership in secondary schools. The subsequent introduction of Universal Secondary Education (USE) in 2007, aimed to ensure that this programme does not only increase educational access, but also improves the schools' education outcomes on an on-going basis (Nsubuga, 2008). Nabayego (2013) shows that education produces graduates who earn more in society, and their results suggest that there is a significant relationship between the cost and quality of education and earning attributable to educational attainment. To support the role of education in social development, Edgell (2006) argues that industrial capitalist society depends on capital-intensive production which is stimulated by a relative increase in skilled manpower produced by the education system Another set of studies in developing countries analyses the relationship between cognitive skills and labour productivity (Bossiere, Knight & Sabot, 1985;Glewwe, 1996). They find that including cognitive skills in the earnings equation has a strong explanatory power. However, these studies myopically look at education in the context of cognitive skills, ignoring the affective and psychomotor skills and their impact on development. But also important to note is that exploring the linkage between education and development calls for the enhancement of values education (UNESCO, 2002). This is so because true development involves a sense of empowerment and inner fulfillment gained from the sort of values gained from schooling (Pieters, 2008). Therefore, the question is what are the roles of schools in the social development process? What part do they play and how do they use the values process to promote development ideas?

To respond to these questions rationally, previous research has indicated that a troubled world experiencing conflict, violence, dehumanisation, poverty, disease, inequality and exclusion needs to invest in education for human development. Schools have to be at the centre of this development (Annan, 2003;UNESCO, 1998).Thelinkage between education and development through the school system calls for the enhancement of values education (Association of Living Values Education, 2010; Pieters, 2008). However, the researchers believe that schools today have failed to utilise values imparted in learning to ignite positive social development in order to build a sense of empowerment and inner fulfilment partly because of the lack of valuesbased learning in schools(UNESCO, 1998; Adelani, 2008). Consequently, schools are producing graduates who are educated but are morally lacking (Genza, 2008), cast in schools with no spiritual stand (Kasibante, 2001), and aesthetically deficient (Mazinga, 2001). Ssemusu (2003:24) upholds that there is an erosion of traditional values in child education where by schools are focusing more on academic excellence rather than promoting Outcomes Based Education (OBE).From the foregoing, the significance of values is identified in the literature and demonstrated that without values in schools we cannot expect sustainable development. How can the school be aided articulate the values in social development? A conceptual frame work indicates this paradigm.

5. III. Methodology

Any research endeavour begins with the identification of an appropriate research approach. A research approach is a method or plan to aid the process of data collection and analysis (Berg, 2004:16). This study was a mixed design of a descriptive type (Creswell, 2009). Qualitative approaches included methods of data collection like document reviews, which concentrate much on the credibility of the participants in the natural setting. Qualitative research approach aims at providing an understanding of a social setting or activity as viewed from the perspective of the research participants (Puchta & Porter, 2004:73). The qualitative research approach is an interactive inquiry in which data is collected during face-to-face interactions, establishing trust between the researcher and the participants. The quantitative approaches used were the structured questionnaire whose analysis was based on frequencies and percentages.

A sample of 120 participants from eight schools of Kampala district schools was used, four schools being primary and four secondary schools. In these schools, 8 principals, 60 educators and 52 learners were interviewed. The data analysis methods were both qualitative and quantitative. Qualitative methods were grounded theory and content analysis, while quantitative methods were use of descriptive statistics of frequencies and percentages. Grounded theory used coding. Coding means naming segments of data with a label or labels that simultaneously categorizes, summarizes, and accounts for each piece of data (Punch, 2009: 43). It is the first step in moving beyond concrete statements in the data to making analytical interpretations (Punch, 2009:45). Coding in grounded theory is centrally concerned with rendering the data theoretically or converting the data analytically. This means using the data to generate more abstract categories, themes and categorisations.

6. a) The school role in tackling social development

The role of the school in social development was the major question of concern. The interviews conducted revealed that the school is an agent of social change. Through being an agent of social change, it provides education to increase skilled manpower needed in industry and in society as ambassadors of social change. One principal in one rural primary school (A) observes:

"Parents bring their children to our school because they expect us to turn these pupils into leaders. The aim of education is to train the head, soul and body therefore these should be felt in an ideal school system".

Similarly, another principal in an urban secondary school (B) had this to say:

7. "The world is transforming into the garden of Aden in total decay because (I think) schools have not played their fundamental part. Civilisation begins at school, but what we (as educators) need to do is to teach our learners to be leaders of creating global awareness of the consequent evils of war and ethnic divides".

However, some respondents still indicated that schools can be partners in social development through imparting academic values that increase skilled manpower to participate in the industrial capitalist society. Industrialisation and urbanisation can be realised where there is skilled manpower for national guidance, as well as making society aware of the social problems surrounding humanity. Education does that; it informs through critical observation and knowledge dissemination. Descriptive statistics were compiled to this effect (see table 2). Source: Field Most participants indicated that education produces role models in society and leaders of tomorrow (40 per cent). Indeed this is championed as the leading driver of schools in Uganda and elsewhere in the world. Being a role mode means you must be exemplary, morally upright, politically active and a persuasive developer and states man. Very few participants realised that education is a tool for promoting inter-cultural dialogue (09 per cent). This is perhaps so because inter-cultural education is a quite new field of consideration in contemporary Ugandan schools, yet as we move towards the East African Community (regionalisation) we need to recognise that inter-ethnic and inter-faith dialogue is handled effectively for social justice ideals. Participants also recognised that schools produce employable products (35 per cent) and moral leaders (32 per cent). But the dilemma today is the emergency of a labour-market paradox that has created more unemployed skilled youth. This means that quality, relevance and entrepreneurship in schools must be emphasized as tools towards sustainable employability.

8. b) What values?

Empirical 3 indicates that most schools integrate academic values (24.5 per cent) because they have deadlines of completing the syllabi. However, this is a wrong notion that has landed our education system into big trouble: mainly the production of theoretical products who cannot change their conditions as well as those of society. The consequent bit is that with the high level of graduate unemployment, many skilled youth cannot self-employ themselves because education has taught them to be White collar job seekers. A relatively large number of participants also agreed that schools impart moral values (18.2 per cent). This is commonly done in religiously based schools. President Kasavubu of the former Zaire (currently the Democratic Republic of Congo) (cited in Mayanja, 2009:13) once remarked that education and discipline are the preserve of moral

9. teaching. Without morals, without love for one's neighbour, education can be harmful because it would lack what should constitute its very essence.

There is evidence to support the above claim. Ganstad (2002:5) argues that educators must favour moral character and conduct where good behaviour must come first. This would be used to counteract a world of hopelessness, war and immorality.

Spiritual (15 per cent) and universal values (15 per cent) are equally imparted in schools as suggested by the participants. As evidence for the existence of spiritual values, in every Christian school there must be a Church as the symbol of divine tolerance and emancipation, just as a Mosque is a monument for the contemporary Islamic school. All these religious symbols depict the yearning by each denominational philosophy of redemptive discipline in such religiouslyfounded schools (Sekamwa & Kasibante, 1985).On the other hand, it is the obligation of every school to promote universal/life values and/or civic values without fear or favour. The government of Uganda endorses the national goals of development as the basis for projecting these universal/civic values in the school structure, but also looks at democratic education as the pillar for building positive citizenship and patriotism (Government White Paper, 1993).

Psychological values (10.7 per cent) are also provided and these include imparting leadership and self-discipline values. Consideration is also given to the social and aesthetic values (8.3 per cent). All School Governing Bodies (Religiously founded, public and private schools) promote and inculcate aesthetic values in learners. Through promoting aesthetic values in schools, Mazinga (2001:8) argues that learners are encouraged to be productive, creative, must possess talents, and possess a love for beauty and excellence in any progressive education system. The exploration of the potential aesthetic abilities of many learners is to develop better entrepreneurial and communication abilities of the learners. Mbuga (2002:14) remarks that the school administration must encourage learners to participate in creative building activities such as public speaking sessions and leadership programmes like campaigning for a prefectorate office in the school, and the compulsory involvement in co-curricular activities as a singular programme for nurturing learners' ingenious potentials. Likewise, a school counsellor's report (2003) reported this:

Finally, the incorporation of social values into school discipline provides learners with life principles required to aid them in their afterlife and to safeguard them from evil tendencies that might deter their progress. Social values are sometimes safe guarded by the schools' rules and regulations. Rules, laws and regulations, when critically observed in most of the schools the investigator visited around Kampala district, highlight the safe-guarding of social order as a cultural obligation. "Observe maximum silence in all important gatherings", was a common nomenclature in most school codes of conduct, "respect your superiors, be it prefects, educators, administrators and support staff" was yet another very important rule of the thumb that cut across many rules and regulations of those schools the researcher got in touch with. The Government White Paper (1993:7-8) on education stipulates several social values which are the mainstays that contribute to the social and economic expansion of society and are part of the goals of national development. Social values point to education for social transformation in preparation of young people for social survival. Social values are emphasized in all schools and SGBs because they define the essence of citizenship.

Who integrates the values is also an important point of observation (See table 3) because the optimal integration of values depends of the person integrating them. The qualification of educational stakeholders in the integration process matters a lot. This is why the researchers were interested in knowing the extent of this matter.

10. Table 3 : Stakeholders that integrate values in schools

11. Source: Field

In table 3, educators integrate values the most (29.2 per cent). This is perhaps because of their professional obligations to the school and classroom where most of these learners interact most. The educators' experiences give them the impetus to handle discipline cases in a decisive, flexible, and democratic manner. Katende's (2008:43) treatise is a great complement to the above thoughts:

"The quality of learning, which the educators get from National Teachers Colleges and Universities in Uganda plus their experience in the profession, is enough to give them the sort of complacency they deserve to reinforce schools with positive values and discipline. Educators' leadership skills and experience are increasingly required in a beleaguered profession like teaching, and in choosing the right values to pass onto the learners."

But also of critical importance is the School Governing Body (20.8 per cent). In light of the role of the SGBs, the Government White Paper (1993) comments, "Their roles are to design school policy and make top disciplinary decisions in line with the school's founding mission and vision". It can be argued that the School Governing Body (SGB) monitors and supervises how school management implements policy including ensuring that values are integrated into school discipline in the best way possible. In Uganda's schools for example, government appoints members of the SGB to formulate policy and oversee schools on behalf of government. The community (17.5 per cent), school counsellor (16.7 per cent) and worship places (15.8 per cent) take peripheral positions simply because they cannot be relied upon since most schools do not have these places, and there is little time spent in these worship places to really transform learner behaviour, Likewise, it is a popular song that Uganda's curriculum is very theoretical and too linear. Such a curriculum cannot facilitate social change in terms of self-employability, entrepreneurial intent for learners (Morley, 2006), leadership in a politically devastated society, and support for social justice education in a multi-cultural society. Principal (C) had this to say: "Often our school syllabus is specific on the learning of traditional disciplines that turn our learners into academic giants. When they get to the employment market, they want an already established job. They do not want to be starters of their own employment".

12. Another said: "Schools try to produce potential leaders, who can transform society by denouncing evil. But the usual fear is for them to come out to attack government on what is not right. I think we should make them role models; to do what is right for others to follow and to educate society about fundamental human rights, equality and democracy".

The unemployment problem has also derailed most young people. The labour market is more capital intensive, with a protection factor by the capitalist (Ryan & Ciavarella, 2002). Machining the age is more preferred than manpower. The youth is thus put in a dilemma of all sorts. An educator had this to say "Without jobs, education has no meaning. Moreover employment is a means to survival. Of parents and guardians send children to school to acquire education to be able to access a job for an earning, then today's unemployment rate suggests that education is meaningless".

13. V. Conclusion and Policy Implications

In conclusion, values imparted in schools are the basis of promoting social transformation where learners must become change agents. The philosophical implication of this is that transforming society cannot be separated from the school. The school is a unit for socialisation. The socialization process is a broader concept that defines school participation in community development and liberal education (Berger, 2001). Values are espoused where the community and school will help protect them. But what happens today is that the school is often isolated from the society and what schools produce as products tend not to match the demands of society. Because schools exist in a pluralist environment where behaviour may be shaped by diverse cultural philosophies, education tends to broadly refine values to be relative human choices. Therefore the concept of values, in the Ugandan school setting, is pegged on the reality that formal education becomes instrumental in pronouncing a set of multiple values (relativism) other than a single value (absolutism), because all values supplement one another in the ethical development of learners. Schools must change their approach; teach learner how to be entrepreneurs through service-based training, as well as teaching peace education, and making patriots.

In conclusion, our attempt in this paper has been to examine the role of the school in articulating values for social development in a globalized environment. From the findings, there is need to reintegrate the school into the demands of society so as to tackle the challenges of development solidly. This further requires an understanding of the policy context of the link between education and society, which policy context is thus observed as the conceptualisation of globalisation impacts on the state of education (Morley, 2003). Globalisation impacts are those elements that affect the quality of industry and the school. Within this process, the learner is an input into the school, and an output into the society (environment). Therefore, linking values-education to social development is a system. This study provides the optimal process of integrating values for social development in a school system using the systems approach (Sekiwu, 2013). It has an input with learners who are agents of social change, educators who integrate values into learners and the school facility or plant which offers tools to facilitate the integration process. In the outer configuration, there is the society (environment) which provides inputs to the school. The environment also receives the finished product as graduates from the school. In other words optimal integration of values for social development is a system, where the school and environment must complement each other.

| Response | % |

| Education produces role models, leaders of | 40% |

| tomorrow | |

| Employable graduates to transform industry for | 35% |

| national development | |

| Patriots in citizenship building | 12% |

| Moral leaders | 32% |

| Education for social justice, peace education | 15% |

| Promoting inter-cultural dialogue | 09% |

| Category of values | Indicators | Freq. | % |

| 1. Universal | Peace, democracy, patriotism, citizenship, Development | 18 | 15% |

| 2. Moral | Behaviours | 22 | 18.2% |

| 3. Spiritual | God fearing, Godly actions | 18 | 15% |

| 4. Social | Respect of social norms and culture, tradition | 10 | 8.3% |

| 5. Academic | Intellectualism | 29 | 24.5% |

| 6. Aesthetic | Being creative, innovative and love for beauty and environmental protection | 10 | 8.3% |

| 7. Psychological | Self-actualisation, leadership, conscience building | 13 | 10.7% |

| Total | 120 | 100.00% | |

| Source: Field data | |||

| Data in table |