1. Introduction

pelling is an important skill taught early on because it is building block for higher level thinking skills and teaches skills that can increase students' overall academic success (Graham, 1999 2013). Spelling helps increase a student's ability to read texts and comprehend passages, and also increases skills in written communication (Graham et al., 2002(Graham et al., , 2004)). Spelling is a complicated and difficult subject to effectively teach students (Wanzek, Vaughn, Wexler, Swanson, Edmonds, & Kim, 2006). Since spelling is an essential skill for academic success, it is important that teachers use tools and methodologies that have been empirically shown to help children in school (Graham, Harris, Fink-Chorzempa, & Adkins, 2004).

Cover, copy, compare (CCC) requires a student to (1) copy the word from a sample (2) cover the sample and write the word from memory (3) check the work for correct spelling and if spelled correctly move on to the next word or (4) if an error was made the student is to copy the word multiple times from a sample. This is an evidence-based self-managed spelling intervention that is inexpensive, does not require intensive teacher training, and is easy to implement and evaluate in a classroom (Joseph, With the large increase in the number of children identified with autism (Heward, 2013), educators need effective teaching procedures to increase their basic academic skills. Unfortunately, there is little research on how children with autism can be taught literacy skills (Mirenda, 2003). There is little research on how to teach spelling to students with autism. Recently, Ivicek-Cordes, McLaughlin, and Higgins, (2012) implemented CCC with a single elementary student with autism to teach him to spell words from the Dolch list. They employed oral prompting and the participant was allowed to write these words after verbal prompting. After the 10 words had been copied and written, the student took a test in a spiral notebook. They found CCC increased the participant's correct spelling of Dolch sight words and the participant was able to progress to an additional list of words. By the end of data collection, the participant was able to improve his spelling of words from the Dolch list. Kagohara, Sigafoos, Achmadi, O'Reilly, and Lancioni (2012) successfully taught two students with autism with video modeling to correctly use the spelling checker. Using a multiple baseline design across students, when video modeling was implemented, student skills in using a spelling check improved and were maintained at follow up. However, many classrooms may not have the necessary technological equipment to implement such procedures. In addition, no data on the actual spelling performance of their two participants were presented.

CCC has been modified in recent classroom research. For example, (Erion, Davenport, Rodax, Scholl, & Hardy, 2010) completed an analysis of the rewriting component of the intervention. The impact of varying the number of times a student copied a word following an error was examined with four elementary age students. During training student performance in both versions of CCC was greater than that found in baseline. Also, there was not a great difference between versions of CCC, and retention over time was similar for CCC1 and CCC3. In the present analysis, we modified the procedures employed by Ivicek-Cordes et al. by having our participant trace the correct spelling of the word in addition to writing the correct word. Second, we employed a different form when the student copied the word. She was allowed to trace the first word and then this was covered and she had to write the word without being able to view the correct spelling. Folding her written work with after she attempted to spell the word from memory was the second modification of CCC.

The purpose of this case study was to evaluate the effects CCC with an older elementary school student with autism. An additional purpose of this study was to replicate (Kazdin, 2011

2. Method a) Participant and Setting

The student in this study was a 12-year-old female enrolled in the sixth grade. She was diagnosed with autism (ASD) by a school psychologist and the school district's intervention specialist when she was 5years old. She qualified for special education with IEP goals in reading, writing, math, behavior/social, and adaptive skills. Woodcock Johnson III (Woodcock, McGrew, Mather, 2008) scores placed her at a 2.4 grade level in academic skills, pre-kindergarten level in writing fluency, and 1.2 grade level in academic applications.

The student was selected for this study based on a recommendation from her classroom teacher because our student's IEP stated that she had not meet grade level standards in writing and requires specially designed instruction to make progress. Her IEP goal in writing stated that when given 3rd grade level high frequency spelling words, the student will be able to spell the words, increasing her accuracy from 0% to 80% over 3 consecutive trials, onteacher created data sheets. At the beginning of the study, the student was able to spell 68 out of 100 words correctly.

The study took place in a separate empty classroom located near a self-contained special education classroom for students with developmental disabilities. The classroom was in a middle income public elementary school in the Pacific Northwest. The classroom consisted of 11students from fourth to sixth grade, two instructional assistants, one master teacher, and one student teacher. The classroom population included students diagnosed Intellectual Disabilities, Autism Spectrum Disorder, and Health Impairments. Eight students in the classroom were eligible for free or reduced lunches. None of the students in the classroom were English Language Learners.

Data were gathered and evaluated by a university student teacher (first author) as part of a requirement for her academic major and instructor certification in special education from the State of Washington and the local private university. The student teacher worked with the student individually three to five times a week in the morning. The study took place in an afterschool daycare room that was unoccupied during the school day to limit distractions. The student instructor sat at a round table facing the student during the sessions.

3. b) Materials

The study used instructor-created spelling tests for the pre-assessments and data collection after each session (see Appendix A). The intervention usedincluded a modified CCC worksheet created by the instructor (see Appendix B). Rather than having the student write on a single sheet of paper, we employed a folded piece of paper. This was carried out to meet the physical requirements for our student. The first authoremployed three sets of 10 words per set. The total 30 words were chosen from a list of third grade high frequency words created by the local school district.

4. c) Dependent Variable and Measurement

The behavior measured in this study was the accuracy of spelling words on a written test. A correct response was writing all the letters in the word in appropriate order. Incorrect responses were defined as omitting a letter, adding an extra letter, substituting a letter, or writing the letters in the wrong order.

Before intervention, the student was given preassessment spelling tests of the 100 words from third grade high frequency list to determine unknown words. Data were collected and scored by marking the correct and incorrect words on a master list (see Appendix C).

At the end of a baseline or CCC session, the student was tested on the 10 words in the set taught that day. Baseline data were collected for other sets on random school days. This was done to keep the instruction and evaluation within the attention span of the student. The instructor read the word orally and instructed the student to write the word. The student was given no time limit for responding.

The first author corrected the spelling tests after the session. A correct response was recorded with a "C" and an incorrect response was recorded with a "X" next to the corresponding word (see Appendix D). Data were counted and transferred to another sheet that recorded the total number of correct responses for each set (see Appendix E).

5. d) Experimental Design and Conditions

A non-current multiple baseline probe design across three sets of words (Kazdin, 2011) was used to evaluate the effectiveness of CCC for spelling the target words. Decisions were made to move on to the next set based upon improving data trends, the social behavior of the student, and or the classroom schedule for that particular school day. Implementing the multiple baseline probe design allowed for some flexibility and reduced the requirement for collecting data each day.

Pre-assessment : The student was given spelling tests of all 100 third grade high frequency words to determine unknown words. The spelling tests consisted of 10 words each and administered on different days. The student was praised for effort and on-task behavior, but not given feedback about response accuracy during the spelling tests.

Baseline : During baseline, the instructor read the words orally and the student wrote them on paper. The student was praised for effort and on-task behavior, but not given feedback about response accuracy during the spelling tests. The number of sessions for baseline varied from 2 to 12 sessions. The number of days between sessions varied from one to ten days. CCC : The student was given sheets of paper with the spelling words in the intervention set. Each sheet of paper included one word from that set. First, she traced the word. Next, she copied the word from the model by tracing it. Then, the instructor folded the sheet of paper to cover the word and the student wrote the word again from memory. This modification was carried out to keep the participant from simply copying the word after the correct spelling had been written. Another modification was when our student compared the spelling words to check for accuracy he had to spell the correct spelling aloud. If the student misspelled the word, she wrote it five times from a model on a separate piece of paper. This process was repeated for all 10 words in the set. At the end of each session, a spelling test was given. e) Reliability of Measurement and Fidelity of the Experimental Conditions.

Inter-observer agreement was collected on 6 of the 13 sessions, or 46% of all sessions. Inter-observer data were collected on a separate sheet using the same procedures listed above. The instructor compared the marks made by each observer to record agreements and disagreements. Mean agreement for this study was 100%.

Fidelity of the intervention was gathered for two sessions. The second author came to the classroom and observed the first author implement either CCC or baseline conditions for the three sets. A simple checklist was employed and used to determine which condition was being employed with which words. Overall agreement for the fidelity of implementing either baseline or CCC was 100%. These data were gathered on only two occasions due to scheduling conflicts with the second author.

6. III.

7. Results

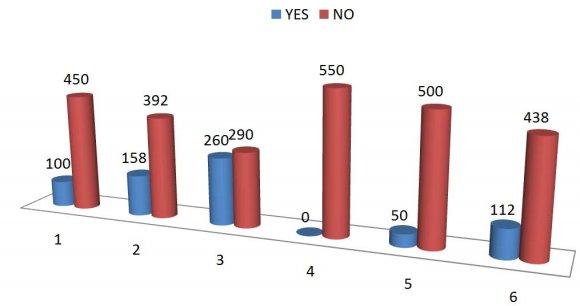

8. a) Baseline

The results for correct responses for each set are displayed in Figure 1. For Set 1, the mean number of words correct was 1.5 words. The student spelled 0 to 3 words correctly during days of baseline. For Set 2, the mean number of words correct was 1.5 words for baseline. For Set 3, the mean words correct during baseline 1.0 words. The overall mean in baseline was 1.33 words correct across all three sets. b) CCC Intervention began on Session 3 for Set 1. Correct responses increased from 7 to 10. CCC was employed beginning with Session 9 for Set 2. Correct words ranged from 9 to 10 with an overall mean of 9.3 words. CCC began on Session 13 for Set 3 words. The student spelled 8 words correctly on Session 13. As our data show, 100% of the outcomes with CCC. Finally, the participant reached 100% mastery for Sets 1 and 2.

IV.

9. Discussion

The CCC method improved the spelling performanceof a single student with autism. These outcomes begin to add to the literature on teaching spelling to students with autism. Also, our overall outcomes replicate the effects of Ivicek-Cordes et al., (2012). However, in the present case report, a more rigorous single case research design was employed. The results also provide an additional replication regarding the efficacy of CCC to teach spelling (Joseph et al., 2012). Also, we were able to modify the CCC form just as others have done so with CCC in math (Grafman & Cates, 2010). However, since only a single participant was employed, our outcomes need to be viewed with caution.

A strengthin the present study was it required no additional cost for the teacher. The materials were constructed by the first author and are found in most classroom settings. No special curricula or technology needed to be purchased. Another strength was that the cover, copy, compare method improved the spelling skills for our participant. It was an straightforwardintervention to implement in a classroom that required little time. Our participant appeared to like being taught withCCC. In the view of the classroom teacher, CCC drew upon her strengths of memorization and learning by repetition. Finally,the participant was very willing to work with the first author on most occasions.

There were also limitations to this study. The implementing and employing CCC required one-on-one instruction. We were never able to fade out prompts to have the student use the method independently as a self-tutoring strategy. Another limitation of this study is the short intervention time period. The time constraint was due to absences, half-days, and winter break. Although the intervention only lasted for 1.5 months, the outcomes would have been stronger if a longer duration of assessing the CCC portion of the study as well as having more data points in the baseline than that used in the present analysis. Also, it would be been more rigorous to have gathered fidelity of implementation of various experimental conditions more frequently. We only gathered these data twice. However, as Harn, Parisi and Stoolmiller (2013), have lamented, two is much better than one measure of treatment fidelity. Clearly a larger number of evaluations should have taken place. In addition, as Horner, Carr, Halle, McGee, Odom, & Wolery, 2005) have indicated, having more than a single participant is needed to make decisions regarding the efficacy of CCC for spelling with children with autism.

However, even with the various limitations of this research, the present case study provides some documentation for the utility of employing CCC for teaching spelling words to an elementary student with autism. It also provides a partial replication of the research of Ivicek-Cordes et al. (2012) and adds to the growing literature as to the efficacy of employing CCC with students with moderate to severe academic issues. Lastly, implementing CCC to improve spelling performance replicates and adds to our confidence regarding the use of CCC in both general and special education classroom settings (Copper et al., 2007;Kazdin, 2011). Cleary, with continuing need to provide data-based and effective instruction to students with autism, CCC appears to have merit for teaching students with autism to spell. The use of CCC with a student with autism remains novel, and additional research is needed with this population.

| II. |