1. Introduction

n the white paper "China's space program: A 2021 perspective", president Xi Jinping stated that "to explore the vast cosmos, develop the space industry and build China into a space power country is our eternal dream". Since 2016, China's space industry develops by leaps and bounds. In the 20th report of the national congress of CPC, Xi also emphasized that "we will move faster to boost China's strength in aerospace development". Young aerospace talents are the backbone of aerospace development in the future, besides, in order to meet the demand of the exploration of the aviation industry for the English proficiency of aerospace researchers, their academic literacy needs to be improved.

An academic article is one of the effective ways to spread aerospace research achievements, share academic insights and gain the international reputation of a country. Moreover, English for Academic Purposes (EAP), as a branch of English language education, has been a hot topic of research in applied linguistics since the mid to late 1960s (Feng J & Hyland, 2020). EAP is often favored by researchers interested in the genre as a tool for teaching discipline-specific writing to L2 learners in professional or academic settings (Cheng, 2018). In order to better spread national aerospace research achievements through academic articles, academic writing and instruction become crucial for both students and educators. Snow & Uccelli (2009) suggest that academic English language proficiency consists of four points: linguistic competence, genre capability, critical thinking skills, and professional knowledge. Academic writing is an important parameter in students' academic literacy (Yang Y, 2016), which is meanwhile a daunting task for students to write because they must master both content and academic competence, especially for English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners and novice writers to successfully master academic writing skills, because it requires a strong knowledge background in the organization of written texts, appropriate language, and vocabulary use (Tangpermpoon, 2008). L2 learners also face additional challenges in developing genre competence (Hyland, 2007). Besides, Swales (2004) also mentioned that Chinese research strength has not yet been fully manifested in various research indices and databases. The same point is also mentioned in Chinese foreign language academia since the 1980s, they have been putting an increasing focus on academic English writing. In recent years, the objective of Chinese English writing research has shifted, laying more stress on the subject instead of the object in class teaching (Yang Y, 2016). Also, theorists and practitioners from genre approaches reflect that writing instruction should be located in the disciplines (Wingate U, 2012).

The above problems show that academic literacy in China remains remedial, the same things happen in other countries, like UK and Australia. Research has suggested that students might not be as ready as expected to explicate and criticize their work with regard to disciplinary writing conventions (Wingate U, 2012). Rather, only when the students develop an understanding of their own disciplinary conventions can the writing practices be challenged and the writer finds his/her own voice and identity (Lo H Y et al, 2014). In view of this, a teaching method focusing on a specific discipline and supported by genre theory is essential.

Wingate U (2012) started an initiative at King's College London, called "writing journey", she used the metaphor by considering writing as a "journey", the destination of the "journey" is to develop the academic literacy of students, while the routes to arrive the destination are different. Here "route" means different instruction methods and materials. Regarding the above obstacles, paying attention to the "route" is necessary for both educators and students. As the genre has become a key concept in EAP (Hyland, 2016) and genre-based pedagogy is a mainstay of EAP instruction, researchers and practitioners should take notice of the benefit of genre-based teaching methods. Therefore, the genre-based approach is an effective "route" by using text analysis to enable students to understand and control the conventions and discourses of their discipline while producing text (Wingate U, 2012), which has become one of the most important and influential concepts in language education (Hyland, 2004).

Notably, previous research on aerospace English mainly focuses on the establishment of aerospace English corpus, discourse analysis, syllabus design, etc. But most existing syllabus does not tallier a specific course that combines both disciplinary contents with genre-based writing instruction. Besides, it is hard to operationalize in the actual classroom. Existing literature made few references to how learners actually analyzed target genres before engaging in their writing task (Cheng 2008). Under such circumstances, a genrebased academic English writing course featured by explicit and systematic instruction related to students' disciplines may be highly beneficial. Yang & Allison (2003) once said that a focus on text organization remains very useful pedagogically. This study focuses on generic pedagogy to sketch some ways from the perspective of how students incorporate genre knowledge into their academic writing and their attitude toward the genre-based teaching model.

2. II.

3. Literature Review a) Genre Analysis as a Supportive Tool in Academic Writing

The word "genre" is derived from the Greek word "category" or "classification" (Hyon, 1996), which was originally applied to literary critics in the 18th century. Traditionally, it was conceived as a collection of fixed conventions. In the 20th century, modern critics have reconceptualized genre as "a dynamic set of conventions", which are associated with changing social purpose (Swales, 1990). Since the 1970s, the concept of genre has gradually penetrated into the field of linguistics (Yumei J, 2004).

John Swales(1990), as one of the representatives of genre analysis, defined genre as "an identifiable communicative event characterized by a set of communicative purposes that occur frequently in a particular professional or academic community and that are accepted and understood by members of the community". Swales believes that genres with relatively consistent purposes should have relatively similar structures. Therefore, professionals and scholars in a particular field should try to maintain this structural form to improve the quality and efficiency of communication (Swales, 1990). The most influential genre analysis framework established by Swales is initially characterized by the analysis of "move" (Swales?2000).

"Move" refers to a section of a text that performs a specific communicative function (Kanoksilapatham, 2007). Swales (1990) explains that moves often contain multiple elements or steps and the function of these steps is to achieve the purpose of the move to which they belong. Some of the moves in a genre are obligatory, in that they are necessary to achieve the communicative purpose of the genre, whereas others are optional, those which speakers or writers may choose to employ if they decide those moves add to the effectiveness of the communication but do not alter the purpose of the text (Hasan, 1989). Based on Swales' genre theory, move analysis is an effective way of discourse analysis in investigating the underlying rhetoric structure of research articles (RAs) in terms of moves and steps for some pedagogical purposes (Moreno & Swales, 2018). An explicit understanding of text structures, linguistic choices, and the purpose of genres is crucial because one of the difficulties faced by EFL students when asked to produce an academic text is that they often have an inadequate understanding of how texts can be organized to convey their purposes (Hyland, 1990).

Regarding this, the aim of genre-based pedagogy that this study adopts is to identify how these moves are organized in a given genre to raise learners' awareness of both rhetorical organization and the linguistic features closely associated with their discipline. By employing Swales' move analysis, researchers analyze numerous texts of a specific genre to identify rhetorical sequences, or moves, in different parts of the writing. Students then learn about these moves to meet their disciplinary writing conventions and criteria (Lo H Y et al, 2014).

Based on the specific role that each part of the academic article plays in achieving the communicative purpose, Swales (1990) first identifies the larger structural parts of a research article, including the introduction, methods, result, discussion, and conclusion section, these individual sections of research article all have certain moves and steps. In terms of abstract, Hyland (2000)'s linear order of five move model was widely used. "Create a Research Space", also known as the "CARS" model was put forward by Swales in 1981 and showed a sequence of three moves that frequently occur in the introduction section of a research article. What's more, through a corpus-based study, Lim (2006) summarized the move structure of the methodology section, which follows three moves. Also, there have been several studies in the result section, including Brett (1994), Nwogu (1997) The above models have motivated many attempts of investigations in various fields, the importance of genre knowledge not only lies in helping language learners to understand and master academic, professional, or educational discourse but also in facilitating learners to follow some conventions of their discipline (Swales, 1990). What's more, the results of move analysis have been successfully used for developing teaching and learning materials (Stoller & Robinson, 2013).

4. b) Hammond's Circular Writing Model

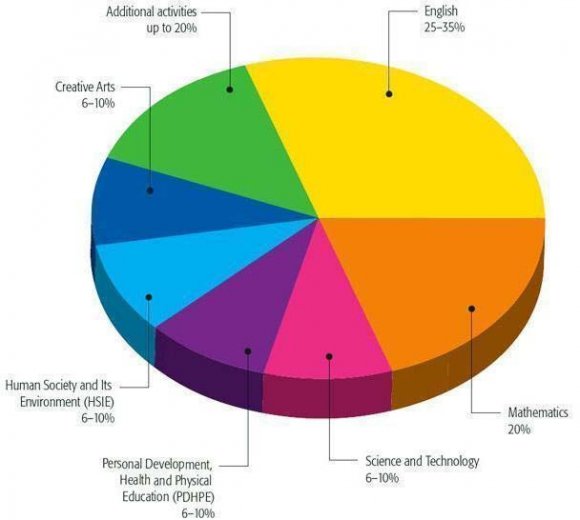

Hammond et al. (1992) proposed a model including two cycles and four stages (see figure 1), this study tries to incorporate this model into aerospace academic English instruction. The above schema consists of two circles and four stages aiming to develop the different abilities of learners. The first circle focuses on developing listening and speaking skills, while during the second circle of learning, students' writing abilities can be improved.

In the first cycle, starting from the first stage called Building Knowledge of the Field (BKOF) where teachers and students build cultural context, share experiences, and discuss vocabulary and grammatical patterns, laying a solid foundation for the next stage. Then comes the Modeling of Text (MOT) where students read or listen to various texts that are geared around a certain communicative purpose, get to know its social and linguistic features and social functions, understand its schematic structure, and receive teachers' feedback. After listening and reading the material that shares the same communicative purposes, students enter the third stage called Joint Construction of Text (JCT). At this stage, learners try to produce spoken or written texts with their peers, and with bits of help from the teachers, students are free to share their academic knowledge and discuss things from different angles and write together. After completing the previous process, students consolidate their understanding of the text's schematic structure, field knowledge, and language patterns through interaction with teachers and their peers. They enter the final stage of the first cycle called Independent Construction of Text (ICT), here, students are expected to write a text on their own (Yang Y, 2016).

The second cycle is aimed at developing the ability in controlling written and spoken texts. Students gain some writing ability from the first cycle and write the text independently in the second cycle. After going through two circles by student-student and classteacher interaction, students will master some genre knowledge in their discipline. The Australian systemic functional linguistics view of genre has promoted several instructional frameworks for implementing genre-based pedagogy (Halliday & Hasan, 1989). The most representative is Rothery (1994), who designed an effective writing cycle (see Figure 2), which can be divided into inner and outer cycles. The outer model includes three modules beginning with deconstruction, in this process, teachers play the primary role in guiding students to identify text organization and key language features. Through explicit instruction, language patterns in deconstruction are easy for students to learn and use, and these patterns can again be applied in independent writing modules (Martin, 1999). Deconstruction is followed by joint construction, teachers-students interaction helps them jointly construct a new text of the same genre, following the general patterns of the models. After this stage, students are dominant and can produce text on their own. As the inner circle suggests, the goal of the pedagogy is both control of the genre and critical orientation towards texts. This teaching and learning cycle in the Australian context are to help students become more successful readers and writers of academic and workplace texts (Hyon, 1996).

The combination of the two cycles can both be the instructional guide of English academic writing classes with a specific discipline. Because the two cycles have the same logic but have a different emphasis, the first cycle proposed by Hammond focuses on genre, while the second cycles emphasize writing instruction. Both cycles are designed to narrow the gap between students by guiding the whole class to deconstruct and jointly construct the expected genre before they attempt independent writing tasks (Rose D, 2015). Regarding this, the two cycles jointly promote students' genre awareness and help them to develop specific knowledge fields and ultimately build distinctive language patterns in a certain genre (Martin, 1999).

5. d) Application of Genre-based Teaching in Disciplinespecific Academic Writing

Genre-based teaching includes both theory and practice, but more attention needs to be paid to empirical and experimental studies related to a different discipline, besides, few studies focus on the aerospace English classroom setting. In order to meet the urgent demand of the aviation industry for the English proficiency of aerospace major students, there is a compelling need for teachers of writing courses in English for academic purposes (EAP) to have a better understanding of how instruction can assist students to achieve their academic goals.

There are some typical latest studies related to specific disciplines supported by genre-based teaching approaches. For instance, Ellis (1998) conducts a contrastive experimental study on how effective a genrebased approach was in teaching the writing of short tourist information texts in an EAP context, and how this method improves learners' ability to produce effective tokens of the genre. The statistic in his study shows that the genre group improved significantly whereas the nongenre group did not.

Jihua Dong and Xiao fei Liu (2020) explored the potential of integrating corpus-based and genre-based approaches to teaching rhetorical structures in engineering academic writing courses at a university in China. The effectiveness of this pedagogical approach was evaluated across pre-and post-instruction questionnaires, interviews, students' reflective journals, and students' writing samples. Their study can be conceived as an attempt at a new integrated method in academic writing instruction.

In order to implement the genre-based teaching approach to aerospace English classes and meet the need of the new situation, Chinese researchers Liu Quan and A Rong's study published in China ESP Research in 2021, proposes a "theory + practice" model of basic English for aviation based on the genre teaching method. Their study proposed that the existing curriculum in vocational colleges is no longer adequate to meet the needs of both teaching and learning. It is important to develop a curriculum based on the needs of students and to clarify the positioning of general English and Aviation English (Liu Quan, A Rong, 2021). This claim reflects the disconnection between general English teaching and students' need. This paper is a good attempt to implement a genre-based teaching method in real aviation English class, and the students' feedback is a positive trend.

All the above cases highlight the potential power of genre as an explicit, supportive tool for building academic literacy (Cheng 2008). Genre-based teaching approach focusing on rhetorical organization can be successful in an EAP or ESP teaching situation, therefore, Students of different majors need to have some linguistic knowledge, especially genre, in this way, they can both achieve their communicative goals and produce well-organized writing (Ellis, 1998).

6. III.

7. Methodology a) Research Design

English for Specific Purpose has long been noted as paying ''scant attention to how people learn, focusing instead on the question of what people learn'' (Hutchinson & Waters, 1987). In order to solve the problem, this study aims to investigate teachers' practices and students' attitudes through classroom observation and post-class interviews. (The author has observed 40 doctoral students' genre-based academic writing classes with mixed majors with more than 20 class hours at Northwestern Polytechnical University, China). The purpose of observation is to explore how students notice and analyze generic features of academic texts and incorporate generic knowledge into their academic writing. However, the students in the observed class have different majors, including Biomedical Sciences, Engineering, Mathematics, Aeronautics, Architectural and Civil Engineering, etc. So, this study attempts to put forward a new integrated teaching method specifically for aerospace students.

8. b) Data Collection

The primary data of this study comes from three types, class observation notes, post-class interviews, and instruction materials of class. Class observation lasts for consecutive 10 classes. During the observation, the author took down some notes about students learning behavior, response, attitude, and teacher's comment during the class. In order to investigate the attitude of students toward the new teaching model, a post-class interview was designed to explore students' attitudes about the current situation in their English class and the genre-based teaching model. The interview lasts for 30 minutes, and there are a total of 10 Volume XXIII Issue II Version I 4 ( ) interviewees majoring in aerospace from the observed classroom, the interviews were semi-structured. The interviews were audio recorded and transcribed in full by Xunfei technology. Instruction materials used in class were used to evaluate the difficulty of the learning material and how these materials facilitate learners' writing.

9. c) Data Analysis

Data analysis proceeded inductively through repeated examination of class observation notes, teacher's comments, and relevant interview statements.

10. d) Research Question

11. How does genre knowledge facilitate students'

English academic writing? 2. What are the students' views toward the new integrated teaching syllabus for aerospace students?

e) Instructional Design Since the students in the observed class were all Ph.D. students and they were all expected to write up and publish their research after the class. Besides, the goal of this academic English writing course is to improve students' academic English proficiency and to be able to write professional academic texts in this field. Focusing on these goals, the implementation of genrebased integrated teaching methods in aerospace English academic writing classes consists of four interrelated stages with the guidance of the two cycles and Swales' move analysis as the theoretical basis. The following is the procedure of class design: The first stage aims to build knowledge of aerospace, in this regard, students are supposed to collect at least ten academic articles published in highimpact factor journals to establish a mini corpus. All the articles are geared around aerospace academic texts and topics that they are going to deal with in the second stage.

The second stage is the most crucial part in this writing "journey". Students start to delineate the macro rhetoric organization of genres and the micro linguistic features of the articles they collected. During this process, genre analysis plays as a kind of critical engagement of text, students are engaged in "deep thinking", they think from the perspective of the writer to see how rhetorical choices are made and talk with the author (Yang Y, 2016). Move analysis helps students figure out the rhetorical structure and communicative purpose of the collected texts. With the help of teachers, students are supposed to first decipher the move structure of articles and figure out the lexicogrammatical features that characterize a move. Then, they need to distinguish the obligatory and optional moves and the communicative purposes of these moves. Teachers can lead students to deep thinking by posting some questions, like "how many moves are in this part of the article?", and "what are the writers' purposes for using these words and expressions?". Teachers are supposed to follow the structure of articles to proceed their instruction. According to Sun Yu (2021)'s study, academic English writing courses should be taught with an understanding of subject-specific content and discourse to help students establish their discipline-specific writing model. Besides, writing in the disciplines requires the subject expert to teach writing as part of the regular subject teaching (Wingate U, 2012). If necessary, this study suggests that two teachers are supposed to jointly conduct the course, one has linguistic knowledge, especially about the genre, and the other should be an aerospace professional or specialist involved in the teaching and evaluation or preparation process for the class. In this way, the whole teaching process will be more effective and professional. After class, the out-of-class assignment on annotating the move structure should be assigned to students.

The third stage is the joint construction of the texts. Students try to write the different parts of articles by imitating these collected articles. Then, it is necessary to have a peer review and group discussion after finishing their writing. At the final stage, they come into the independent construction stage, after finishing their own work, teachers' evaluation will do a lot of help.

After going through the above genre-based teaching procedures, students are supposed to become more observant readers of the discoursal conventions of their fields and thereby deepen their rhetorical perspectives on their disciplines (Swales & Lindemann 2002).

IV.

12. Results and Discussion

The post-class interview interviewed 10 students whose major is aerospace at Northwestern Polytechnical University, China. According to the time period in which students were exposed to genre knowledge, the questions of the interview were divided into three main sections, before-class, during-class, and post-class questions, corresponding roughly to the concerns of the two research questions. During the process of the interview, the interviewer explains the new teaching method to the interviewees to see their attitude towards this integrated teaching method. The interview questions and students' responses are as follows:

Question 1: Do you have academic English writing classes related to your major before? 7 students mentioned that they have classes on academic writing like the observed class, in which the students have different majors and attend the class together, but no tailored instructions focus on their major, and three students didn't have such a class before. Besides, in traditional academic writing classes, teachers will lecture them on some general rules that fix most of the disciplines. Students think this way of teaching is ineffective.

Question 2: How did you learn to write and publish your academic article before?

In this question, most of the students say that they learn it by themselves by reading a lot of articles related to their research, finding the rules from these articles, and imitating the structure, but this is quite timeconsuming. Other students say that academic writing always makes them headache, because they haven't learned how to write academic articles systematically before, so they don't know where to start. Most of the students pointed out that analyzing the move structure and identifying the communicative purpose of each move is the most difficult because some of the moves and their communicative purpose are not always clear. Students pointed out that their focus on academic writing has shifted from the sentence level to a deeper level, they concern more about how they convey information instead of the information itself, and how to accurately express their views is crucial. They start to enjoy reading different samples so they can see how these articles are organized and catch the authors' points. The genre-based method can make them become more confident and interested in writing academic articles than before. Students generally hold a positive position towards this new teaching model, they say that the new teaching method is different from the traditional one, it has specific instructions related to their major and a detailed analysis of the structure of the articles. Especially the two teachers jointly conducting the writing class are innovative and may do a lot of help. Hopefully, this method will become common in universities to meet their needs instead of going astray.

The above interviews reveal the attitude of students toward the new teaching model, which mainly comes from three perspectives:

Before taking the genre-based academic writing class, this interview reveals the problem that the traditional general English classes cannot meet students' academic writing needs, the general English class most students have taken is quite superficial and fundamental, which only presents students with simple vocabulary, sentence, and grammar teaching and exercise. This kind of class cannot contribute to academic literacy improvement but may help in their fundamental English abilities. So, there is a disconnection between the current university English curriculum and the needs of students' desire of improving their academic ability. During the class, students seem to be more confident and feel motivated after the instruction because they seem to have some clues on academic writing. After hearing the new teaching model put forward by this study, most of the students give high comments on this syllabus design, because they think the class provides the theoretical basis for academic writing. This kind of genre-based teaching makes students' writing output more operable.

The Genre-based teaching method offers students an explicit understanding of how target texts are structured and why they are written in the way they are (Hyland, 2007.) This integrated method not only can be applied in aerospace English academic writing classes but also in other disciplines.

V.

13. Conclusion

Hyland (2003) in his work gives us a strong and powerful explanation of the function of the genre-based teaching method, he said that by making the genres of power visible and attainable through explicit instruction, genre pedagogic seek to demystify the kinds of writing that will enhance learners' career opportunities and provide access to a greater range of life choices. The genre-based pedagogy has opened new horizons in front of course designers, materials developers, language educators, and second language learners. Previous teaching practice, classroom observation, and students interview show that the new integrated genre-based teaching approach enhances the students' genre knowledge, stimulates students' interest and motivation in writing, and promotes collaborative learning in the process of writing, proving that the genre-based approach is an effective method of teaching academic writing at university, which is worth promoting.

Volume XXIII Issue II Version I

14. G

As a different discipline has a different rhetoric paradigm, this study aims to inspire students to be more flexible and break out of their mindset in their discipline, instead of conforming to the prototypical structure of the texts or applying a "one size fits all solution" in academic writing. However, as this study only shows a model of teaching in aerospace English academic writing class, further researches are necessary to implement and promote this method in real aerospace English class. Future research also can specify the design and improvement of genre-based course aims, content, and structure, more importantly, teachers' training and support are also needed.