1. I. Introduction

enerally, both women and men are found concentrated in certain occupation, face similar conditions at work and experience the same workplace hazards. In sub-Saharan Africa region, working women are also traditionally responsible for the household chores. However, both sexes are physically different and women are more sensitive considering their reproductive roles. It is therefore expedient to recognise these differences and examine critically the exposure of women to workplace hazards in order to enhance reduction in maternal mortality and morbidity that are rampant among the developing nations.

Deaths, accidents and infections from the workplace have been contributing immensely to the global mortality rate. Annual death toll from unsafe occupation reported for 2006 was 1.1 million people. The recorded cases of fatalities in the workplace that led to complete disability was about 300,000 out of 250 million while over 160 million people were victims of work-related diseases (ILO, 2006;WHO, 2006;ILO, 2008;WHO, 2010). Gender variations are difficult to specify especially for a low-income economy. The global figures for 2008 show that out of 337 million occupational accidents, 358,000 were confirmed as fatal, while deaths from occupational related illnesses were 651,000 (WHO, 2010; ILO, 2006;ILO, 2008;Lu, 2011). Observation from these data show that there is a 77 percent increase in death toll from unsafe workplace between 2006 and 2008, 35 percent increase between the same period while the number of fatal accident increased by 19 percent.

Women make up 45% of the employed population in the EU (European Agency for Safety and Health at Work, 2012), they constitute about 31.2 percent of Nigeria labour force (Eweama, 2009; National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), 2010). Across the Eastern, Middle, Western and Southern Africa regions, about 37, 25, 22 and 2 percents of girls respectively in age between 10 and 14 were economically active in the year 1990 (ILO, 1990;Bledsoe & Cohen, 1993).

The proportion in the next older age (15-19 years) was 62, 39, 45 and 29 percent respectively in the same year (ILO, 1990;Bledsoe & Cohen, 1993). In Nigeria, the proportion of women in labour force is unfavourably compared to the men. A change in this paradigm as currently been driven by gender equality agenda (including equal employment opportunities and support for women enterprises that were enshrined in MDG 3 (UN, 2003; NPC & USAID, 2004; Oyekanmi, 2008; Commission on Legal Empowerment of the Poor, 2008) can only be successfully achieved with the provision of safe working environment for women. The concentration of women in micro-enterprises with diverse methods of operations makes it more important to address the gender dimension in health and safety at workplace. Healthy and safe work environments can enhance, and are synonymous with quality jobs and output (Muir, 1974;Alli, 2001).

It is envisaged that quality outputs would impact on women's earnings and might keep them in employment. Thus, attention must be paid to the health and safety of the jobs that women do.

However, men and women are not the same neither is their jobs and the working conditions they are exposed to the same. Likewise, the way they are treated in the society also differ. These factors can affect the hazards they face at work and the approach that needs to be taken to assess and control them. Women are always at the receiving end of most social and economic hazards (National Population Commission and USAID, 2004) and street trading is not an exception. While studies have shown some interrelationships between unemployment, earnings and poverty and G economic growth, the impact of work conditions on the most vulnerable gender in terms of their reproductive well-being has not been conspicuous in the literature (Kwankye, Nyarko. & Tago, 2007; Beavon, 1990;Callaghan & Venter, 2011;Lantana, 2010, Motala, 2002, NBS, 2011;Walker & Gilbert, 2002).

In general, women's health is not only in terms of the well-being in female anatomy, it is a constellation of medical situations, their susceptibilities and responses to treatment for sicknesses and diseases (WHO, 2006). It also includes those bio-demographic problems which they face directly or indirectly in their day-to-day activities (Walker & Gilbert, 2002;WHO, 2006). While the medical dimension concerns with sensitive areas especially female genitalia, breasts, pregnancy and child birth, the social dimension encompasses physical fitness, mental and social wellbeing (WHO, 2006). Also, while most medical challenges are addressed in the health centers, the social aspects would require interdisciplinary approaches like epidemiology, biostatistics, environmental and community health, behavioral and occupational health synthesis (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2005). In this context, the social aspects of women are considered as they relate to the health risks inherent in their day-to-day trading activities especially on the street.

2. II. Objectives of he Study

The thrust of this study is to assess women in street trading business in urban centres of Nigeria and the implications of the job on their health. It is specifically meant to share information on the interrelationships between women's health and associated street trading risks. Also, the study examines the association between the incidence of injury experience by street hawkers, harassment and traders' socio-economic background. It thereafter proffered applicable strategies for formal re-structuring of street trading business in Nigeria.

3. III. Literature Review and Conceptual Framework

Comprehensive data on occupational hazards and illnesses due to street trading activities are not common especially in developing nations. Available information relates to street trading activities in South Africa, Ghana, Kenya and India (Mitullah, 2004;Lund, 1998;Lund & Skinner, 2003;Ebigbo, 2003;Nirathron, 2006;ILO, 2006;Kusakabe, 2006;Skinner, 2008;Sylvia, 2010). Studies that dissect gender variations in street hawking activities and their health are not popular in Nigeria.

However, with the magnitude of people engaging in the trade, the bad road and unmanageable manner of traffic suggests that such activities cannot be free of hazards. By definition, "work hazard" means the danger or risk encountered in doing or carrying out specific operation in the workplace. A work hazard is a potential damage, harm or an adverse health effect the worker experienced from working or exposure to certain working conditions that include the materials, substance they use, the process and the practice involved in that job (Lu, 2005). Lu (2011) observed that occupational hazards and health challenges vary by occupational sector and the specific job of the individual.

The nature of street trading in Nigeria is such that can be engaged in by anyone because the job only requires low human and financial capital unlike like other businesses in the informal sector. It is a form of microentrepreneurial business. Besides, in most countries, street hawking forms a crucial part of the logistics structure and in most cases serves as the last channel in the chain of production, distribution and consumption.

Specifically, street trading entails displaying wares by the roadside, carrying head pan or raising a sample of wares to the commuters while these vehicles are moving. Thus, the road is being shared between sellers and the motorists. Although, the congestion emanated therein could slow down vehicular speed, the ensuing hustling and bustling in the midst of seemingly uncontrollable 'traffic jam' is likely to be dangerous for women health (Wayne, 1997; Lee, 2004; Ekpenyong & Sibiri, 2011). The health hazards involved in running after a moving vehicle in an attempt to sell goods to the buyers is risky in nature taking into consideration that they (the hawkers) have no control over the traffic. Therefore, cconsidering street trading, it is not unlikely that women could suffer from musculoskeletal disorders as a result of the nature of the trade which entails long standing or running on the roads.

Lu (2011) categorically indicates that certain hazards can lead to some forms of occupational illnesses, and that in most cases, women are more vulnerable. Their exposure can lead to tiredness, pains, headache, lesser birth weight and risk of spontaneous abortion in the case of pregnant women. These sicknesses cannot by any means exclude other reproductive dysfunctions that are medically associated with stress, high blood pressure and unhealthy job conditions.

Vagaries of adverse health effects related to street trading include but not limited to body injuries (accidents), diseases, changes in the way the body functions, growths, effects on a developing fetus (teratogenic and fetotoxic effects), decreases in life span, change in mental condition resulting from stress, traumatic experiences, to mention but few (Lu, 2005; ILO, 2009; Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety, 2009; Agius, 2010). While some of these diseases manifest immediately, others are delayed, and some may not be revertible. Workplace hazard can cause harm or adverse effect to an individual or the organization. Hazard is simply conjectured (in this context) as those working conditions

4. Global Journal of Human Social Science

Volume XII Issue W XV Version I

( D D D D ) A 2 48Year t communities they impact. The chance or probability that a worker will be harmed or experienced adverse health effect if exposed to a hazard is regarded as risk. It also necessary to indicate here that the gravity of the adverse health the worker suffers is a function of the duration of the exposure, health status of the person exposed and the severity of such conditions the work exposed to (Agius, 2010). Therefore, considering the seemly 'fragile' health condition of women and the 'modus operandi' of street trading, it is not likely that their feminine nature will be able to cope adequately with trading activities on the highways. Perhaps if they are able, the long-run effects could be dangerous. Where both men and women traders compete for the same customers under the same conditions, it is not unlikely that women will be more exposed to hazards therein. ). The theory indicates that stress raises blood pressure, engenders sleep and gastro-intestinal disturbances, cause back pain, tension, headache and palpitation. Adapting this theory, Irniza (2011) confirms that there is a significant correlation between urban traffic policing and respiratory symptoms of asthma, exposure to particulate matter, mental stresses and so on. It is indicated that the prevalence of stress is higher among urban traffic police officers compared to others (Irniza, 2011) and that exposure to air pollution have negative effects on mental health and well-being. Thus, if traffic police are susceptible to the above health challenges, then women that trade in the traffic (street traders) should be more vulnerable taking into consideration that they are already overwhelmed with fear of harassment by government authorities or associations.

Besides, these highlighted symptoms and their effects (both in the short and long run) would be inimical to women generally and could be more dangerous to those in child bearing age and the young folks who are the future mothers. In another perspective, work stress has been confirmed capable of influencing coronary heart disease, heighten anxiety, depression and burnout, to mention but few of them (Folkman, et al, 1986;Palmer et al, 2004;Blaug et al, 2007). While this study is not a causality study, the suspicion correlation between health challenges and workplace health hazards in a country with high level of maternal mortality coupled with innumerable number of women in the business, should be worrisome. Street hawking is a b) Research Methods

The study assessed women in street trading business in urban centres of Nigeria and the implications of their jobs on their health. It adopted quantitative research and 'non-participatory direct observation approach' in gathering information on the "modus operandi" of street trading activities in Nigeria. The study also dissected the health risks associated with street trading activity and proffer 'auctionable' strategies towards free-health-risk hawking in Nigeria and sub-Saharan Africa.

The data used in the qualitative segment were extracted from 3,873 street traders data collected from the Central Business Districts (CBDs) areas across three major cities of Nigeria, namely, Lagos (in the South-west), Kano (North west) and Port Harcourt (South-south). The data was collected through structured face-to-face interview among the street traders. Only the women data (n = 1,613) was therefore extracted and analysed for this section. Since, there is no doubt that economic effects impact on individuals differently and by age, it was considered necessary, to analyze the data according to specific age grouping. Also, more than 22 items of trade were recorded in the open-ended question but only 9 categories emerged after the 'axial coding' procedure. Quantitative data were thus analyzed using a combination of univariate and multivariate analyses in determining the interrelationship among the variables of interest. The information from non-participatory direct observation was also presented as complement to survey results.

5. IV. Results and Discussions a) Socio-demographic profile of respondents

As typical of any nation with younger population, the result shows that there is higher proportion of women street traders in the younger age group (15)(16)(17)(18)(19)(20)(21)(22)(23)(24)(25)(26)(27)(28)(29)(30)(31)(32)(33)(34). The average age of women traders is 26 years indicating that the majority of women street traders are young women in their prime of age (Appendix I, Table 1). More than half of the women (53.2 percent) were single as at the time of the survey while the separated, widowed or divorced were 4.1 percent and about 42.7 percent were married as indicated in table 1. The high proportion of singles accounts for the migratory nature of the traders. Respondents in this category could be regarded as 'adventurers' who move in and out of the environment in search of greener pasture. The age distribution of the women street traders depicts a normal distribution with the peak concentrated at age 25-34 years and declining after age 44 (Table 1). The result among others also indicated that 1.1 percent of the traders are below 15 years of age. While the under-15 are not expected to be Out of the three geo-political zones selected for the study, women from the south-east geo-political zone constitutes about half of the traders interviewed. The proportion from the south west is 44.6 percent while only 6.5 percent of the women are from the north-west. The reason that could be adduced for this lower proportion could be the 'pudah' practice in the North. The women are not permitted by Islamic tenets to work and their movements are so restricted to the households. The religion affiliation statistics indicated that Muslim only constitutes 19.2 percent while eight out of every ten women street traders interviewed are Christians.

Another important socio-demographic variable analyzed is the number of children ever born (CEB) by the respondents. This typically measures the average number of children that a woman has ever given birth to. In this context, all the women interviewed were asked to indicate the total number of children they have ever had. This is used among other things, to evaluate their fertility behaviour and to provide an overview of the likely economic burden of children on their trading activities. The result (as indicated in table 1) shows that average CEB is 4 children and 71.4 percent of the respondents are at zero parity. This corroborates the earlier findings that larger numbers of the traders are singles. This is a fundamental characteristic that makes them more vulnerable to physical and job mobility. In addition, the proportions that have five children and above are only 3.8 percent (table 1).

The employment status is used to categorize the ownership of business into employees, apprentices, family workers or own-account workers. The result of the analysis shows that eight out of every ten women street traders are 'own-account workers'. Precisely, 84.1 percent claimed to own the business they are doing (Table 1). Those that are working for family members or directly receiving wages from the activities and the volunteers are 7.6 percent. The employees constitute only 6.5 percent while those that are under training (i.e. apprentices) are less than one percent (Table 1).

Several variables were used in evaluating the vulnerability of women in street trading activities to workplace hazards. Prominent among them are the nature of the trading, product category, frequency of selling articles on the roads, experience of harassment, frequency of engaging in other secondary occupations, etc. These variables are selected to assess the vulnerability to stress and other associated health risks inherent in them. The result shows that about half of the respondents (48 percent) are peddlers who rove (move along) on the roads to sell their wares while the sedentary traders are 52 percent. This latter group involve individual sellers who are seemingly desk-bound e.g. sellers that uses table tops, makeshift shops, spread their wares on the ground or use display glass boxes by the road side. The result also indicates that half of the women interviewed are constantly 'sharing' the road with the 'moving vehicles' in an attempt to sell their wares. The non-participatory observation shows that an average peddler runs after a moving vehicle to sell his stock. Where the transaction could not be completed before the vehicle accelerates or moves away speedily, the ware or the money is flung to the road by the 'boarded buyer' and the peddler tactically wait for a safe opportunity to pick up the money or the wares as the case may be. Occasionally, those goods are driven on by careless drivers which results into losses for the seller. As indicated in the theory ( Lu, 2011;Irniza, 2011). Because they have no control over the movement of the vehicles, they can suffer extortion. Commuters may not pay the correct amount before the vehicles 'roll away'. Notwithstanding that higher proportion of them are not married, the stress in street trading can make their bodies to be worked-up. This might become dangerous to their reproductive lives either presently or in the future.

Among the profound discoveries from this study is the rising rate of assault or harassment suffered by the street traders. The survey indicates that more than half of the women street traders have experienced one assault or the other in the course of plying their trades. Precisely, 55.4 percent of the women have fallen victims to such harassment while trading on the streets, 43.6 percent claimed they have never experienced any harassment as shown in table 2 (Appendix II). In the same vein, one in every five women street traders has been injured while trading on the road and 52.1 percent of respondents have witnessed or seen their colleagues injured in the course of trading on the road (Table 2). These revelations are pointers to the degree of work hazards that the women are exposed to. Various harassments indicated range from bullying, beating, seizure of wares, forceful extortions while rape is not impossible (Palmer & Cooper, 2004; Lee, 2004). Although, there is no causal link between the harassment suffered and the injuries sustained, it could be conjectured that these kinds of harassment as observed and also indicated by the respondents could possibly lead to injuries. Harassing these traders in the

6. Year

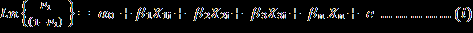

The study further assessed the respondents' earnings notwithstanding the sensitive nature of the measurement and that it is always fraught with challenges (Moore, Stinson & Welniak, 1997;Davern, 2003). Notwithstanding however, respondents were asked to indicate their total income per week and their average daily expenditure. The result shows that the average sale per day is less than N2,500. 86.6 percent of the women sell below N10,000 worth of goods daily. Those that record between N10,000 but less than N20,000 worth of goods are 9.2 percent while only 2.2 percent sell goods worth N20,000 and above as shown in table 1. The observed daily expenditure is not commensurate with the total weekly sales observed. Majority of the respondents expended up to N5000 as their daily expenditure while 13.2 percent indicated more that amount as their daily expenditure. Although, no further verification was made on these claims, the non-participatory observation indicated that it is not likely that their businesses cannot cater for their daily upkeeps on the basis of the volume of wares they carry or sell on the street. Among the specific reasons for involving in street hawking are inability to secure formal jobs, constraints (including finance) in gaining admission to higher school and joblessness of the family's breadwinners. b) Logistic regression estimating the relationship between selected profile of respondents and vulnerability to workplace hazards Only one hypothesis was tested to confirm the interrelationship between activities inherent in street trading and the incidences of injuries among the operators. The variable "ever injured" is interchanged with workplace hazards. A logistic regression analysis was used in testing this hypothesis. The model is depicted as:

Where, ? o represents the intercept, e implies the residual value (or the error term). The Xs are the various street trading activities selected as predictors while the Beta (?) denotes the coefficients of the Xs. The Pi and (1-P 1 ) means the probability of sustaining injury and the probability of not sustaining injury respectively.

Is therefore represents the log of the ratio of probability of incidence of injury to the log of probability of no injury.

The result of the analysis shows that all education categories, nature of trading, religion affiliation, and the intermediate age group (15-24 years) are negatively associated with incident of injury. Positive associations were observed among location of study, employment status, marital status searching for other jobs, employment status, marital status and the intermediate age group of the respondents and incident of injury.

Specifically, the result indicated that respondents with primary, secondary and tertiary education are 0.879, 0.553 and 0.818 less likely to be injured while trading on the street compared to individuals who have no formal education. However, only secondary education is statistically significant (Pvalue = 0.015). Similarly, while migrants from the south are 1.827 times more likely to experience workplace hazards, their counterparts from the north will be 2.678 times more likely to be exposed to incidence of injury. The results are statistically significant at p-values 0.014 and 0.005 respectively. The significance influence of religious affiliation indicated that the Christians and Moslems traders are 0.153 and 0.235 times less likely to experienced injury on the road compared to the tradition region (p-values of 0.019 and 0.075 respectively).

The result further indicated that only the intermediate age (15-24 years) is negatively related and are 0.801 times less likely to be involved in accidents on the street than other age categories. This group is more agile in nature and possesses the ability to swift movement which could aid them to escape or 'dodge' accident. In the same vein, those in age group 25-34, 35-44 and the under aged (less than 15 yrs) are 1.023, 1.024 and 1.599 more likely to experience workplace accidents vis-à-vis the reference category (age 45 and above). Marital status is observed not be significantly related to the incidence of injury.

Women who have experienced harassment are 1.195 times more susceptible to injury compared to those who have never experienced any form of harassment while running their businesses on the streets. Overall, the model summary shows 81 percent accuracy though the interrelationship evaluated is relatively week as shown by Cox & Snell R Square of 0.043 and Nagelkerke R Square of 0.068.

7. V. Conclusion and Recommendations

The result of the analysis shows that street trading is a risky type of business activity that makes women to be more vulnerable to workplace hazards. The exposure of women in this regard should not be Street Trading Activities and Maternal Health in Urban Areas of Nigeria taken for granted. Besides, maternal health could undoubtedly be negatively affected as a result of perennial physical exhaustion, physical abuse and inherent stress in street trading. However, the fact that the magnitude of women participating in street trading is high implies that its re-organization will yield economic dividends for the nation. Without gainsaying, the job has provided opportunities for entrepreneurship and self-employment. However, the impact of the business on the welfare of the operators is not very obvious at least if weekly income is compared with high weekly expenditure recorded in the study. This would be likely impairing opportunity for re-investment and as such keep the women poor continuously. The authors suggest that due recognition be given to the activity and street traders-government initiative or partnership be put in place in order to safeguard the health of the operators.

8. Global Journal of Human Social Science

| Socio-demographic Variables | No | % | Socio-demographic Variables | No | % | |

| Geo-political Zone | Employment Status | |||||

| South-West | 720 | 44.6 | Self Employed | 1356 | 84.1 | |

| South-East | 788 | 48.9 | Employee | 105 | 6.5 | |

| North-West | 105 | 6.5 | Unpaid family worker | 115 | 7.1 | |

| Total | 1613 | 100.0 | Apprentice | 28 | 1.7 | |

| Age Group | Volunteer & Others | 9 | 0.5 | |||

| Less than 15 years | 17 | 1.1 | Total | 1613 | 100.0 | |

| 15-24 years | 536 | 33.2 | ||||

| Year | 25-34 years 35-44 years | 557 241 | 34.5 14.9 | Earning per week (N) Less than N2,500 | 659 | 40.9 |

| 2 54 | 45-54 years 55-64 years | 87 23 | 5.4 1.4 | N2,500 -N4,999 N5,000 -N9,999 | 472 264 | 29.3 16.4 |

| Volume XII Issue W XV Version I ( D D D D ) A | 65 & above Total Mean age = 25.9 years ? 26 years Marital Status Never married Married Separated/Divorced Widowed Total Religious Affiliation Christianity Islam Traditional | 152 1613 858 689 24 42 1613 1296 309 8 | 9.4 100.0 53.2 42.7 1.5 2.6 100.0 80.3 19.2 .5 | N10,000 -N14,999 N15,000 -N19,999 N20,000 & Above Total Average Expenditure per Day Less than N1,000 N2,000 -N2,499 N2,500 -N4,999 N5,000 -N7,999 N8,0,00 & Above Total | 109 39 34 1577 870 408 122 38 175 1613 | 6.8 2.4 2.1 97.8 53.9 25.3 7.6 2.4 10.8 100.0 |

| Global Journal of Human Social Science | Total Educational attainment No Schooling Primary Education Secondary Education Tertiary Education Total Source : Street Trading Survey 2011. | 1613 195 277 761 380 1613 | 100.0 12.1 17.2 47.2 23.5 100.0 | Children Ever Born (CEB) Zero parity 1-2 children 3-4 children 5-6 children 7 & above Total | 1152 175 225 55 6 1613 | 71.4 10.8 13.9 3.4 0.4 100.0 |