1. Introduction

lobal migration is expanding significantly in the twenty-first century (Chan, 2018;Sanchez, 2019) with an estimated 272 million people world-wide living outside their place of birth (World Economic Forum, 2020). This figure is predicted to rise to 405 million by 2050 as a direct result of the effects of environmental changes, new global political and economic dynamics, and growing demographic disparities. These immigrants have left their country of origin and make up more than 3.5% of the world's population (World Migration Report, 2020).

Economic immigrants travel to another country in order to improve their standard of living due to insufficient job opportunities in their origin countries (William et al., 2019). These economic immigrants' functional adjustment is critical to multiple stakeholders, including immigrants themselves, their receiving governments, and local communities. Immigrants are often used to resolve labour shortages, but governments try to maximise the influx of highly-skilled economic immigrants, while minimising the entrance of low-skilled migrants, refugees and asylum seekers (Fossland, 2012;Besharov et al., 2013;Chan, 2018).

Receiving countries benefit from migration through its stimulation of growth in terms of economic, educational, technological, infrastructural, and demographic factors (William et al., 2019). The importance of economic immigrants that could benefit the receiving countries has prompted this study's main objective, which is to investigate how to further enhance their settlement process.

Among the most active migration receiving countries, Australia is one of the four most important countries or regions, proportionally ahead of the United States, United Kingdom and Canada (Oudenhoven, 2006;Liu-Farrer, 2016). About 7.5 million people living in Australia in 2019 were born overseas which is just under 30% of Australia's resident population, and 76% of these immigrants are of working age (Australia Bureau of Statistic, 2019). From the top ten immigrants' origin countries, seven are non-English speaking countries which do not share the same culture with Australia. Immigrants from different culture and speak different language are likely to experience adaptation difficulties or known as acculturative stress (Walker et al., 2011;Lee et al., 2018) which will be further discussed later in this paper.

Australia depends heavily on migration for population growth and provision of workplace skills especially for South Australia as one of the most active receiving-state in Australia, yet still under-populated (Seetaram & Dwyer, 2009;Collins, 2013). From the statistics shown, it is evidenced that economic immigrants are vital for South Australia's economic and employment development where this study was conducted which in return to positively boost immigrants' arrival in this state.

Immigrants are usually studied from the perspective of their mobility and work-related activities (Bove & Elia, 2017) and the role of leisure in immigrants' settlement has been receiving much attention by scholars (Budruk, 2010;Walker et al., 2011;Cohen et al., 2015). The attention from researchers started to be acknowledged from a comprehensive review of leisure journal articles, from the concept inception through to 2005, which identified pioneer studies on migration and leisure (Floyd et al., 2008).

To further understand the significance of leisure in assisting immigrants' settlement, there is a need to include the elements of emotional connectedness to their new home and community. Leisure participation is likely to develop immigrants' attachment to place and community. Shinew and colleagues (2006, p. 405) argue that:

?Given that communities and neighborhoods are becoming progressively more diverse, leisure opportunities and events that help foster a sense of community and build social capital among residents will be important? This notion is supported by Floyd and colleagues (2008, p.14) who noted the importance of studying immigrants' attachment to their new home and community:

?In particular, there is a need to know how leisure contributes to a sense of place and community where communities are forming and restructuring due to immigration? This current research expands the theoretical discourse around the relationship between the migration experience and acculturative stress, in the context of the escalating rate of migration. More specifically, it examines the role that leisure plays in assisting economic immigrants to adjust effectively to their new home country, to integrate with the community and in relieving the acculturative stress.

Through a survey conducted with economic immigrants in South Australia, this paper explores the potential mediating effect of community embeddedness in the relationship between economic immigrants' leisure participation in assisting them to manage acculturative stress. To examine this relationship and the mediation effect, a conceptual framework is proposed and analysed to signal future research directions in the leisure and migration field. Therefore, the aim of this research is to examine the relationship between immigrants' leisure participation and acculturative stress mediated by community embeddedness.

2. II.

3. Literature Review a) Acculturative stress

Successful immigrant settlement is essential to both their own well-being and the benefits they can offer to host countries. However, immigration is by nature a disruptive life event. During the process of relocation, immigrants frequently experience a variety of complex emotions, including depression and the stress caused by settlement difficulties (Adler & Gielen, 2003;Driscoll & Torres, 2020). Furthermore, government immigration department requirements can make the settlement process even more challenging. New economic immigrants often experience multiple difficulties associated with searching for employment, for example, visa policies, skills and qualifications mismatch with local standards, lack of work experience, language proficiency, local contacts and awareness of how to apply for jobs in the new country (Australia Bureau of Statistics, 2019). Thus, strategies to assist economic immigrants to overcome these challenges are essential to ensure effective settlement (Berry, 1997;Walker et al., 2011).

Integral to the migration experience is adjustment to a new culture -acculturation. Acculturation is defined as the process of adaptation, whereby two cultures, the immigrants' original culture and the host society's culture, are reconciled (Berry, 2006;Sam & Berry, 2006). Acculturation causes five general changes in immigrants' lives, including physical, biological, cultural, social and psychological (Berry, 2006;Benson & Osbaldiston, 2016). However, these changes may vary depending on the multiple acculturation strategies adopted by immigrants. There are four variations in how immigrants seek to engage in the process that includes assimilation; individuals do not wish to maintain their cultural identity and seek interaction with other cultures, separation; individuals prefer to maintain their original culture and wish to avoid interaction with others, integration; individuals have an interest in both keeping their original culture while having interactions with other groups, and marginalisation; individuals have little interest either in maintaining their original culture or in having relations with others from the new culture (Berry, 2006;Agergaard et al., 2015).

The third strategy, integration, is likely to have the most positive effect on immigrants' acculturation and leads to effective adaptation. This strategy can be successfully pursued if the host society supports cultural diversity and open settlement opportunities for immigrants (Agergaard et al., 2015;Burdsey, 2017). However, other variations of outcomes in the acculturation process have been reported, namely, behavioural shifts and acculturative stress (Berry, 2006). Immigrants who can change their behaviours to fit in with their new cultural environment experience less problematic acculturation and adapt more easily. However, in most cases, immigrants experience acculturative stress, causing them various difficulties and challenges (Berry, 2006;Agergaard et al., 2015).

Acculturative stress refers to a set of stress behaviours which occur during immigrants' acculturation, such as compromised mental health due to uncertainty, anxiety and depression. They might also suffer from feelings of '? heightened psychosomatic symptom[s]' (Berry et al., 1987, p. 492). The major causes of acculturative stress are language barriers, perceived discrimination, loss/nostalgia for their country of origin, and not feeling at home (Aroian et al., 1998;Walker et al., 2011). These stressors negatively affect immigrants' life satisfaction, self-esteem, mental health, and socio-cultural adaptation (Kim et al., 2009).

4. b) Immigrants' connection to a community

Another significant factor in understanding the role of leisure in assisting immigrants' settlement is the extent of their emotional connectedness to their new home and society. Leisure participation is likely to develop attachment to community (Stedman, 2006;Luo et al., 2019).

Community embeddedness , which involves bonding or social interaction between a person and their society, is a strong predictor of quality of life (Baker & Palmer, 2006;Treuren, 2009;Treuren & Fein, 2018) and is likely to reduce acculturative stress. Although the phenomenon of acculturative stress has been acknowledged in the migrant labour literature (e.g. Lee, 2013;Negi, 2013), further exploration is needed on the link between leisure participation and adjustment in assessing the development of community embeddedness. Therefore, it is important to investigate the development of immigrants' attachment to their new home and community through leisure.

5. c) Conceptual framework

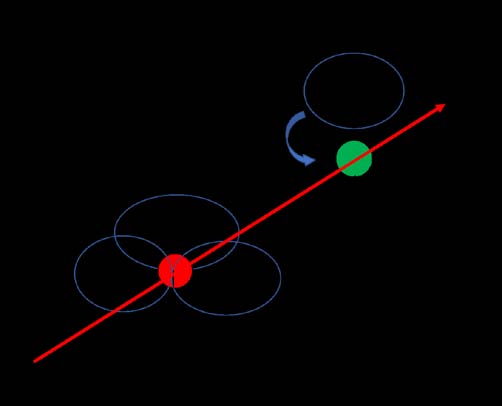

To further understand the relationship between immigrants' leisure participation, community embeddedness and acculturative stress, the present paper develops and analyses a conceptual framework (see Figure 1) drawn from connections with the literatures discussed in this section. The relationship between acculturation and acculturative stress has been increasingly investigated in the leisure field (Korpela, 2019). Leisure is likely to be one remedy for acculturative stress. Leisure participation can help immigrants to adjust to their new environment through subsequent greater social support and cultural understanding (Choi et al., 2008;Chai, 2009;Kim et al., 2011'). Engaging in leisure activities offers a potential space for developing a comfortable life (Blackshaw, 2010). Studying the effects of immigrants' leisure participation is therefore important in understanding the role of leisure in the management of acculturative stress.

problems (Sharaievska et al., 2010;Walker et al., 2011;Suto, 2013), create a sense of belonging (Groves, 2012), encourage cross-cultural social interaction (Stack & Iwasaki, 2009;Kim, 2012;Yakunina et al., 2013) and promote family bonding (Stodolska & Livengood, 2006).

Leisure has also been shown to contribute positively to immigrants' settlement by promoting their self-esteem (Kim et al., 2005), improving their economic situation and overcoming their language difficulties (Jiali Ye, 2005; Wolin et al., 2006). All these findings are aligned with Coleman and Iso-Ahola (1993), who were among the first researchers to theorise the beneficial role of leisure -that it can reduce life stress and consequently contribute to the maintenance of physical and mental health. Therefore, as depicted in the proposed conceptual framework, it is important to investigate the role of leisure participation in helping with immigrants' settlement.

6. Relationship 2: Leisure participation and community embeddedness

The second relationship in the proposed framework is the mediation of community embeddedness in the relationship between immigrants' leisure participation and their level of acculturative stress. Community embeddedness involves bonding or social interaction between immigrants and the community, away from the working environment (for example, leisure participation) (Treuren, 2009;Yang et al., 2011). The community embeddedness construct includes three dimensions: (1) degree of fit (an individual's compatibility and comfort within the community), (2) level of linkage (the extent to which an individual is linked to other people and activities in the community), and (3) sacrifice (perceived loss of the material or psychological benefits that may be forfeited by leaving the community) (Felps et al., 2009;Treuren & Fein, 2018). Participation in leisure activities creates social engagement (Arai & Pedlar, 2003;Kim et al., 2012) and has the potential to facilitate immigrants' attachment to their new local community (Tirone et al., 2010), which may enhance community embeddedness, buffer stress, reduce perceived discrimination and alleviate mental health problems (Choi et al., 2008;Jibeen, 2011;Walker et al., 2011).

Community embeddedness appears to have a significant negative relationship with acculturative stress and is a strong predictor of quality of life (Verile et al., 2019). Social interaction is demonstrated to enhance positive well-being, reduce stress (Jibeen, 2011;) and promote life satisfaction (Powdthavee, 2008) Understanding how immigrants experience social interactions in their daily lives is essential to identifying ways to enhance their community embeddedness (Ho & Hatfield, 2011). Defining this relationship offers the potential for further theory development, as well as practical benefit for both economic immigrants and their employers, through a better understanding of the importance of out-of-work activities for becoming embedded in the community and promoting well-being. The role of community embeddedness in promoting economic immigrants' quality of life leads to our inclusion of this construct in our conceptual framework. The framework anticipates that economic immigrants' leisure participation can be expected to increase community embeddedness and therefore play a role in reducing levels of acculturative stress.

7. III.

8. Methodology and Results

9. a) Data collection

The survey questionnaire was designed according to the research objectives, which emphasise the relationship between immigrants' leisure participation and their acculturative stress. The survey also includes the important mediator proposed in the conceptual framework -community embeddedness. The scale items used to measure each construct of the proposed research framework were selected based on a comprehensive review of the literature to identify valid and reliable extant measures.

This quantitative investigation employed samples from the population of South Australian economic skilled immigrants, recruited by using nonprobability sampling methods, including accidental/ convenience, purposive and snowballing (Chua, 2011). This approach was considered practical for this case, given that the immigrant population is massive and changes regularly (Collins, Onwuegbuzie, & Jiao, 2007).

The questionnaire was developed and administered in English. Immigrants with skilled-visas were assumed to have competent English proficiency as they need to achieve a satisfactory reading score on the IELTS (International English Language Testing System) before they can be granted a skilled visa to migrate to Australia (Australian Department of Immigration and Citizenship, 2011). This government requirement provided reasonable assurance of respondents' ability to comprehend the survey.

The survey starts with a section which was designed to gain information about respondents' most preferred leisure activities that they were actively involved in during their settlement. Respondents were also asked about their participation frequency. Six categories of leisure activities (i.e. social, cultural, sport, recreation, physical and hobbies) were comprehensively listed based on previous literatures (Gayo-Cal, 2006; Hills et al., 2000; Lloyd & Auld, 2002) and Australian leisure trends (Veal, 1992; Veal, Lynch, & Darcy, 2013). Respondents were allowed to choose multiple activities/ events.

Based on previous literature, acculturative stress measurement items were divided into four dimensions, also known as stressors: language barriers, not feeling at home, feeling loss/nostalgia, and perceived discrimination (Aroian et al., 1998;Walker et al., 2011). Measurement items for community embeddedness were divided into three dimensions: fit to community, community-related sacrifice, and link to community. Fit to community represents immigrants' compatibility and comfort within the community. Community-related sacrifice represents immigrants' perceived loss of material or psychological benefits that would be forfeited by leaving the community. Link to community represents immigrants' connection with other people and activities in the community (Felps et al., 2009). Community embeddedness measurement items were designed to explore immigrants' attachment to the local community during their settlement. These questions were customised to suit this present study's setting and requirements. Some of the items needed rewording to make respondents understand that they needed to respond based on their psychological feelings towards the stressors. Respondents were asked to indicate their agreement to the statements on a fivepoint Likert scale (Likert, 1932).

The questionnaire was conducted through an online survey. The survey was distributed via Facebook, emails to the researcher's personal contacts, representatives/heads of migration departments and associations, and migration agents. A total of 481 responses was received (45% response rate). After an initial data screening process, a total of 395 usable cases remained, with the removal of unemployed respondents (n=29), incomplete responses (n=53), and outliers (n=4). Three other statistical procedures were then applied to this data analysis -descriptive statistics, Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), and mediation regression.

10. b) Results

Descriptive statistics were computed for all variables to enable identification of each variable. This section consists of respondents' socio demographic profiles, leisure participation data, descriptive statistics of variables, EFA findings, and mediated regression findings. The results are presented in a quantitative form.

11. c) Socio demographics and leisure participation

The socio demographic results showed that the respondents were considered appropriate to serve this study's purpose, based on several factors. Most of the respondents were aged 26-45 years, representing 79% of the sample. Approximately 71% of the respondents were married/partnered, and the majority had completed a postgraduate degree. In terms of years of settlement (1-10 years), 10% of respondents represented each of the years. Approximately 67% were permanent residents and the rest had already been granted Australian citizenship. Seventy-five percent of the respondents were Asian, and the remaining percentage were immigrants from Africa and Middle East. This sample group served the purpose of the study in investigating immigrants who do not share the same culture with Australians. Almost 64% of them working full-time.

The majority of the respondents (68%) were involved in social leisure activities (e.g. eating out, pub/drinks, visiting friends/family, religious activities, and community activity), with cultural activities (e.g. library, museum, art gallery, concert, theatre, and ethnic events) and physical activity (e.g. fitness activities, weight training, aerobics, walking, running, and spa) in second and third positions. Social integration plays an important role in immigrants' leisure participation. They need to interact with people and gain social support in assisting them to overcome their settlement difficulties. Sixty-five percent of the respondents participated in their leisure activities regularly (i.e. at least once a week). Most of the respondents pursued their leisure during non-working days with friends (55%), spouse (48%), and family (39%).

12. d) EFA for community embeddedness and acculturative stress

EFA reveals the underlying factor structure of the constructs and the interrelationships among the variables. The appropriateness of data for factor analysis was tested using Keiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett's test of Sphericity (Bartlett, 1954;Kaiser, 1970). These tests were to establish the factorability value. Two important issues in determining the suitability of the data set for factor analysis are sample size and the strength of the relationship among variables (Pallant, 2013).

The analysis of the EFA for community embeddedness yielded one factor of community fit and sacrifice (see Table 1). The examination of the correlation matrix of community embeddedness scale revealed that all coefficients are above 0.3 except item CE02 and CE08. Besides revealing low loadings, these items asked respondents' opinion on weather and safety which are not related to their engagement with the community. Therefore, these items were eliminated.

After eliminating the low loading items, the test was performed again. The Keiser-Meyer Olkin value was .886, exceeding the suggested value of .6 (Kaiser, 1970) and Bartlett's test of sphericity (Bartlett, 1954), ?2 (15) = 7044.030, p<0.001, also reached statistical significance, supporting the factorability of the correlation matrix.

The principle axis factoring performed on community embeddedness revealed only one relevant factor, as did the scree plot, contradicting the previous literature (i.e. , which reported two dimensions (i.e., fit to community and communityrelated sacrifice). This study decided to retain only one factor, renamed as community fit and sacrifice. Fit to community represents immigrants' compatibility and comfort within the community, and community-related sacrifice represents immigrants' perceived loss of material or psychological benefits, which may be forfeited by their leaving the community. The analysis of the EFA for acculturative stress yielded four factors: language barriers, not feeling at home, feeling loss/nostalgia, and perceived discrimination (see Table 2). The examination of the correlation matrix of acculturative stress scale revealed that all coefficients were above 0.3 except item AS02, AS06 and AS09. These items were low loaded and redundant with other items in their designated factors, therefore deleted from the analysis. AS02 asked about the difficulties of undertaking daily activities because of language barriers, which is similar to item AS01 and AS03 in the same factor. Similar to AS06 that asked about respondents' feelings about missing home, this item was redundant with the other items in the same factor (i.e., loss/nostalgia). AS09 asked about spare time activities which, according to previous literature, was grouped in the loss/nostalgia dimension. Item AS09 was a positive statement and respondents' answers to this item was not consistent with the other negative items. Although reverse coding to this item was performed prior to EFA, the result still revealed low loading. Furthermore, this item did not seem to belong to the dimension and was therefore eliminated from the analysis. After eliminating the low loading items, the test was performed again. The Keiser-Meyer Olkin value was .783, exceeding the suggested value of .6 (Kaiser, 1970) and Bartlett's test of sphericity (Bartlett, 1954), ?2 (36) =18073.623, p<0.001, also reached statistical significance, supporting the factorability of the correlation matrix.

The principle axis factoring performed on acculturative stress unveiled four factors with eigenvalues more than 1 and close to 1, although the scree plot gives unclear evidence, prompting this study to refer to previous literature and the statistical results. The statistical result supports previous literature that has determined that acculturative stress has the four dimensions noted above. The survey also asked four open-ended questions to support the overall findings. Almost half of the immigrants were involved in their own ethnic community events and leisure activities, indicating that immigrants' involvement in their own community and the local community is well balanced and that they adopted the 'integration' acculturation approach. Approximately 66% (positive responses provided by 261 respondents out of 395 total respondents) of them agreed that leisure involvement is beneficial, especially in facilitating social integration. However, they also agreed that they experienced various constraints preventing them from enjoying their leisure activities, including lack of time due to work and study, financial issues, and family commitments. Leisure is beneficial to immigrants in managing their acculturative stress and settlement, although settlement challenges can still limit their ability to participate in leisure and heighten their stress. Findings on leisure constrains and settlement challenges will not be discussed further in this paper as it will be published in a different article.

13. e) Mediated Regression Analysis

The aim of the mediated regression analysis was to determine the relationships between the independent variable (immigrants' leisure participation) and the dependent variable (levels of acculturative stress) with mediating effect, the mediator being community embeddedness.

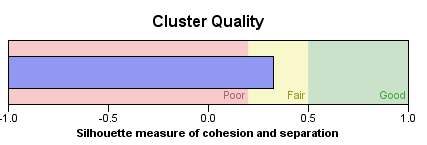

Table 3 presents the mediation regression results. The partial mediation effect of community embeddedness was found between the immigrants' leisure participation and not feeling at home type of acculturative stress (.267***). The direct relationship between leisure participation and not feeling at home stress was at .330***. Therefore, when the community embeddedness mediator was added, the result decreased to .267***. Leisure participation has a direct positive significant relationship with community embeddedness (.109*). The community embeddedness mediator has a negative significant direct relationship with the not feeling at home type of acculturative stress (-.584***). The analysis showed that married and Middle Eastern migrants have the highest not feeling at home stress when participating in leisure. Another partial mediation effect of community embeddedness was found between immigrants' leisure participation and the perceived discrimination type of acculturative stress (.302***) (see Table 4). The direct relationship between leisure participation and perceived discrimination stress was at .329***, with the result decreasing to .302*** when the community embeddedness mediator was added. The community embeddedness mediator has a negative significant direct relationship with perceived discrimination type of acculturative stress (-.448**). African immigrants have the highest perceived discrimination stress when participating in leisure activities. By contrast, leisure participation has no significant direct relationship with language barriers stress and feeling loss/nostalgia stress, therefore no further examination was performed. Figures 2 and 3 provide a clearer picture of the significant mediation relationship between leisure participation, community embeddedness, not feeling at home stress and perceived discrimination stress. This study's results show that immigrants' leisure participation has positive significant relationships with not feeling at home stress and perceived discrimination, although this is reduced when the community embeddedness mediator is included in the relationships. To confirm the significance of the mediation regression result, a Sobel test (Sobel, 1986) was conducted. For the mediation effect of community embeddedness for both relationships, the p value was at 0.03 (p < 0.05). Therefore, these mediation relationships are considered significant.

14. Discussion and Conclusion

The study offers a response to concerns about the adjustment difficulties of immigrants that lead to acculturative stress. The results from the mediation regression analysis addressed the four research objectives. This study has made a significant contribution by demonstrating that immigrants' leisure participation impacts significantly on their levels of acculturative stress and affects the development of community embeddedness. The study found that leisure participation is positively related to community embeddedness. The examination also confirmed that community embeddedness reduces not feeling at home and perceived discrimination stress. With the mediating effect of community embeddedness, leisure activities alleviated the stress associated with not feeling at home and perceived discrimination. Attachment to the society provides comfort to immigrants and helps prevent them from feeling discriminated against. Furthermore, social leisure was found to be the most beneficial approach for immigrants to reduce their stress, especially when associated with their own ethnic community events (see Figure 4).

Volume XX Issue X Version I Wang & Sunny, 2011). Leisure is also a platform from which to learn about new cultures, promotes an active lifestyle, and encourages social networking (Venkatesh, 2006;Xu et al., 2018).

The relationship between leisure and social connection has been the major finding of this study. The benefits of social leisure include encouraging social integration and the promotion of cultural awareness, leading to community embeddedness and thus the potential to share the settlement experience with their own ethnic community ( ). However, without good English skills (in the Australian context and other English-speaking countries), the process would be meaningless, with poor English proficiency argued to be a leisure constraint. In this study, these caveats are less relevant, given that the respondents are mostly skilled visa holders. Their admission to Australia was based on their academic and employment qualifications, meaning that communicating in English was not a critical issue. Thus, the study indicated no significant relationship between immigrants' leisure participation and levels of language barrier stress.

Employment opportunity is another benefit of social leisure for immigrants. Immigrants are likely to meet people with the potential to introduce them to job opportunities. For most economic immigrants, the most important goal after relocating to a new country is finding a good job. Developing a strong social network increases their chances of getting a job (Hasmi et This study contributes to the body of leisure knowledge in theory, practice, and methodology. The study validates the view that, in a South Australian context, a theoretical basis exists to support the practicability and utility of immigrants' leisure participation in assisting them to manage acculturative stress. The study also recognises the viability of community embeddedness in enhancing the relationship between leisure and acculturative stress.

The study has advanced existing knowledge regarding the predictive relationship between immigrants' leisure participation and acculturative stress with the mediation of community embeddedness. The results provide further scope for the exploration and understanding of the important relationship between leisure and migration.

From a practical perspective, this present study offers valid and reliable evidence that can be used by immigrant resource centres, migration departments, immigrant associations and other establishments that provide services to assist immigrants' early settlement. This study's findings may assist the organisations to identify elements of leisure participation that help immigrants to manage their acculturative stress with social integration. The relationships established in this study will provide these organisations with a tool which can be used to better understand how social leisure helps immigrants to alleviate acculturative stress. The study also allows such services to understand other settlement difficulties that hinder immigrants when attempting to participate in leisure activities. These organisations need to give more attention to immigrant settlement in the early years, especially through programs to encourage the social interaction of immigrants. Programs such as sporting events, social gatherings and outdoor recreational activities could help immigrants to feel welcome, learn about other cultures, become familiar with local systems and open more opportunities for employment.

As the field of leisure and migration research develops, the pathways and methods used to pursue future explorations will arrive at, and achieve, high levels of erudition and complexity. This study brings the field a step closer to understanding the relationships between immigrants' leisure participation and acculturative stress. The possible additional elements of attachment to community enhance the potential of immigrants' leisure participation in managing settlement distress. Further research on immigrants and leisure is recommended to obtain a more in-depth understanding of immigrants' settlement challenges and how leisure participation affects immigrants' adjustment. This research has established a framework for the future development of a research agenda of this kind.

| Code | Items | Factor Community fit and sacrifice | Communalities | Cronbach' s alpha |

| CE04 I think of the community where I live as a home | .863 | .745 | ||

| CE03 | The community where I live is a good match for me | .852 | .727 | |

| CE01 I really love the community where I live | .784 | .615 | ||

| CE07 | People respect me a lot in the community where I live | .699 | .489 | .864 |

| CE06 | Leaving the community where I live would be very hard | .607 | .369 | |

| CE05 | The community where I live offers the leisure activities that I like | .550 | .303 | |

| Extraction Method: Principal Axis Factoring. | ||||

| Rotation Method: Oblimin with Kaiser Normalization. a | ||||

| Factor | |||||||||

| Code | Items | Perceived discrimination | Loss / nostalgia | Not feeling at home | Language barriers | Communalities | Cronbach's alpha | ||

| I feel stress when | |||||||||

| AS12 | local Australians treat | .977 | .943 | ||||||

| me as an outsider | |||||||||

| I feel stress when | |||||||||

| local Australians do | |||||||||

| AS11 | belong not think that I really to the | .977 | .924 | 0.945 | |||||

| Australian community | |||||||||

| As a migrant, I feel | |||||||||

| AS10 | stress if people treat me as a second-class | .805 | .735 | ||||||

| citizen | |||||||||

| When I think about my | |||||||||

| AS07 | past life, I feel | .914 | .869 | ||||||

| emotional When I think about my | 0.924 | ||||||||

| AS08 | past life, I feel | .909 | .846 | ||||||

| sentimental | |||||||||

| I do not feel that | |||||||||

| AS05 | South Australia is my | -.989 | .884 | ||||||

| true home | |||||||||

| Even though I live and | 0.919 | ||||||||

| AS04 | work here, it does not feel like my home | -.706 | .849 | ||||||

| country | |||||||||

| I feel stress when | |||||||||

| local Australians have | |||||||||

| AS01 | a | hard | time | .889 | .856 | ||||

| understanding | my | ||||||||

| accent | 0.748 | ||||||||

| Talking in English | |||||||||

| AS03 | takes a lot of effort for me and makes me | .640 | .489 | ||||||

| feel stress | |||||||||

| Extraction Method: Principal Axis Factoring. | |||||||||

| Rotation Method: Oblimin with Kaiser Normalization. a | |||||||||

| IV | Not feeling at home | Community embeddedness | Mediated by community embeddedness |

| Leisure participation | .330*** | 0.109* | .267*** |

| Community embeddedness | -0.584*** | ||

| Married | .355** | ||

| Middle East | 1.553* |

| IV | Discrimination | Community embeddedness | Mediated by community embeddedness |

| Leisure participation | .329*** | 0.109* | .302*** |

| Community embeddedness | -0.448** | ||

| African | 1.987* |