1. Introduction

aniel Bar-Tal & Dikla Antebi (1992a) introduced the concept of siege mentality, defining it "as a mental state in which members of a group hold a central belief that the rest of the world has highly negative behavioral intentions towards them" (p. 634). It is a cognitive state describing a situation in which other groups or nations are perceived to have intentions to do wrong or inflict harm on one's own group or a nation. Such a belief, formerly called as Masada Syndrome (Bar-Tal, 1986), is accompanied by thoughts that a nation is "'alone' in the world, that there is a threat to their existence, that the group must be united in the face of danger, that they cannot expect help from anyone in time of need, and that all means are justified for group defense" (Bar-Tal & Antebi, 1992a, p. 634). Despite the fact that Bar-Tal and Antebi (1992a) emphasized that the crucial focus of siege mentality was on the rest of the world or out-groups that had highly negative intentions toward one's own society (a belief in the negative attention of the world), we argue that the content of siege mentality belief refers to a more complex sociopolitical-psychological phenomenon. According to the content of general siege mentality scale (Bar-Tal & Antebi, 1992a), we could have concluded that it encompassed not only the cognitive repertoire (CR) but also a potential behavioral repertoire (BR): (1) the existence of perceived national threat (CR), (2) experience of a hostile world (CR), (3) mistrust and suspicion toward other nations (CR), (4) the need for an internal national and political homogenization (BR), and (5) the existence of readiness for a warlike defense (BR). As a matter of fact, the behavioral component of siege mentality is implicitly noted by the authors when they say that "the study of group's siege mentality is of special importance, since it may shed light on various groups' behavior" (Bar-Tal & Antebi, 1992b, p. 252). Insomuch as such a cognitive -behavioral schema, as siege mentality actually represents, may be the bases for understanding different kinds of hostile inter-ethnic and international relations that could be largely destructive and might have a sinister effect on the group's life, the investigation of its socio-political (social alienation), socio-cultural (right-wing authoritarianism), and psychological (primary psychopathy) underpinnings seem more important. It is in that sense that we speak about social and psychological underpinning of the Bar-Tal and Antebi's concept of general siege mentality.

It is reasonable to assume that siege mentality is a consequence of historical memories and "especially primed by contextual objects and events" (Bar-Tal & Antebi, 1992a, p. 635). It was specially emphasized that "siege mentality is not an inherited disposition or a stable trait, but a temporary state of mind that can last for either a short or long period of time, depending on the group's perceived experiences and on the educational, cultural, political, and social mechanisms that maintain it" (Bar-Tal & Antebi, 1992b, p. 252). However, we wanted to question the position that siege mentality is not a relatively stable trait of personality and is exclusively depending on historical memories, the group's perceived experiences and political contexts. Given the psychological meaning of siege mentality within the context of intergroup threat theory posed by Stephan & Renfro (2002), siege mentality represents much more a realistic than symbolic threat. Namely, a realistic group threat indicates the existence of a threat to a group's (nation's) power, resources, general welfare, i.e. where other groups (nations) threaten the very existence of its own group or nation (Stephan, Ybarra & Morrison, 2009). If we compare the definition of siege mentality as "a central belief that the rest of the world has highly negative behavioral intentions toward" its own group (Bar-Tal & Antebi, 1992a) and the definition of a realistic threat as an experience "when members of one group perceive that another group is in a position to cause them harm" (Stephan et al., 2009, p. 43), especially referring to physical harm or a loss o resources, we can note the sociopolitical-psychological similarity between the concept of siege mentality and a theoretical position of a realistic group or national threat consists in the fact that there is the existence of external enemies who are perceived to endanger and threaten one's own group or a nation. Thus, we can conclude that external realistic group threats are underlying siege mentality. In other words, siege mentality is the product of or generated from an external threat perception, implying most often the perception of existing external enemies i.e. intergroup threats. But, what about a social internal threat perception that may be underlying siege mentality? Are there some internal social, cultural, and individual factors producing and generating siege mentality, implying the perception of internal i.e. threats existing within the same society? Is it possible that the members of a group perceive its own society as sources and origins of national threat perception in the form of siege mentality, or some personality predisposition would contribute to the emerging of siege mentality?

2. a) Social Alienation

Social alienation is defined as perceived formlessness in a society, expressing distrust toward other people, feeling social powerlessness, and feeling meaningless in one's life (Seeman, 1959(Seeman, , 1983;;?ram, 2007, 2009). Such a social perception and personal feeling can surely generate a kind of collective and individual threat. In other words, social alienation can be defined, as "the subjective reflection of social conditions of powerlessness, the inability to achieve goals, and the absence of supportive, trusting relationships" (Ross, 2011, p. 288). These social cognitions or socially alienated beliefs and attitudes come from reality and therefore present realistic perceptions of social conditions (Mirowsky & Ross, 2003). Insomuch as social alienation presents a realistic perception of social condition the people live in, we could treat social alienation as a kind of realistic threat generating from an interaction between person and society.

3. b) Right-wing authoritarianism

The second concept we put in relationship to siege mentality was right-wing authoritarianism. Authoritarians show a strong tendency to uncritically submit to authorities, are adherent to social norms and tradition, and express a general aggressiveness toward those who violate these norms, rules, and values (Altemeyer, 1981(Altemeyer, , 2006)). It was posited that actual or perceived threat was a significant predictor of right-wing authoritarianism (Onraet, Van Hiel, Dhont & Pattyn, 2013) and hypothesized that various forms of threat may contribute to authoritarianism (Feldman & Stenner, 1997). In other words, higher levels of external threats were related to higher levels of authoritarianism. Given such a relationship between perceived threat and authoritarianism, it seems that threat perception is an antecedent of authoritarian attitudes (Onraet, Dhont & Van Hiel, 2014). However, there is a bidirectional effect between threat perceptions and authoritarianism (Rippl & Seipel, 2012). In other words, having right-wing attitudes may lead to an increased threat perception (Sibley & Duckitt, 2013). In addition, there is a mediator of the threat-authoritarianism link. Mirisola and his associates (2014) have shown that societal threat fosters right-wing authoritarianism via the mediation of the loss of perceived control (Mirisola, Roccato, Russo, Spagna & Vieno, 2014).

4. c) Primary Psychopathy

Levenson, Kiehl, and Fitzpatrick's (1995) concept of primary psychopathy encompasses the affective-interpersonal characteristics. This subtype of psychopathy indicates the existence of a pathological personality style that is affectively cold and interpersonally deceptive (Neumann & Pardini, 2014). Primary psychopathy encompasses individuals who are selfish, uncaring, callous, unemotional, manipulative, and show a lack of remorse (Levenson et al., 1995). It can be defined in terms of interpersonal dysfunctions (Cleckley, 1982;Snowden, Craig & Gray, 2012) or be defined as a cognitive-interpersonal model characterized by a coercive style of relating to others that is supported by expectations of hostility (Gullhaugen & Nottestad, 2012). Given that perceived threat can play a significant role in the correlation between personality traits and attitudes (Sibley & Duckitt, 2008; Sibley, Osborne & Duckitt, 2012), we expected that psychopathy would be associated with siege mentality as a sort of threat perception. For instance, psychopathy has been shown to have associations with negative intergroup attitudes and behaviors (Hodson, Hogg & MacInnis, 2009).

5. d) Aims and Hypothesis

Thus, the aims of our research was to find out (1) whether social alienation, right-wing authoritarianism (RWA), and primary psychopathy have significant effects on the Daniel Bar-Tal and Dikla Antebi's concept of general siege mentality (GSM), and (2) whether the components of the path model are invariant across different ethnic groups, i.e within Croatian ethnic majority group, Serbian ethnic minority group in Croatia, and Croatian ethnic minority group in Serbia. Based on prior direct or indirect research findings, we hypothesized that social alienation (as a socio-political component of the model), right-wing authoritarianism (as a socio-cultural component of the model), and primary psychopathy (as a clinical-psychological component of the model) underlie siege mentality across different ethnic groups. Our second hypothesis was that structural models of the examined variables within different ethnic groups will be variant within different ethnic groups who had different perceived experiences and historical memories, as a legacy of greater Serbia war against Croatia led in the 90-ties in the last century. It was reasonable to expect that ethnic belonging would significantly moderate relations between the variables.

6. II.

7. Method a) Participants and Procedure

The survey was carried out on the adult population in the region of eastern Croatia where live Croats and Serbian ethnic minority, and in the northern region of Serbia (The Province of Vojvodina) where live the members of Croatian ethnic minority. The convenience and the purposive sample consisted of 1431 full aged participants (Croats: N=555; Serbian ethnic minority in Croatia: N=555; Croatian ethnic minority in Serbia-Vojvodina: N=321). The mean age of participants was 44.10 (SD=15.83), 48 percent were males, 52% were females. Correlations among sociodemo graphic characteristics are presented in Table 1. We can see that ethnic subsamples were mainly equalized as to the sex, age, and school attainment (statistically significant correlations between ethnicity and some sociodemo graphics are due to a very large sample). The older participants had a lower degree of school attainment what is regularly expected. The selfreport questionnaires were administered to respondents in their own homes by the interviewers. The respondents were asked to fill the questionnaire by themselves. The filled questionnaires were picked up by the interviewers the next day. This research report is a part of a much larger investigation from the field of political science, sociology, and psychology.

8. Measures

Four measures were applied: (1) general siege mentality scale, (2) social alienation, (3) right-wing authoritarianism (RWA), and (4) primary psychopathy. The responses of the first three measures were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale: 1. strongly disagree, 2. disagree, 3. neither agree nor disagree, 4. agree, 5. strongly agree. Primary psychopathy was measured on a 4-point Likert-type scale: 1. strongly disagree, 2. disagree somewhat, 3. agree somewhat, 4. strongly agree.

General siege mentality scale (GSMS). The scale was constructed on the basis of the conception of Masada Syndrome presented by Bar-Tal (1986). The GSMS was comprised of 12 items. The items included feelings of loneliness in the world, negative attitudes toward the world, sensitivity to cues indicating negative intentions of the world, increased pressure to conformity within the in-group, and use of all means for selfdefense (Bar-Tal and Antebi, 1992). The items of the GSMS are presented in Table 1 in the Appendix.

Social alienation. The scale is constructed on the basis of basis of Seeman' concept of alienation (Seeman, 1959) and an earlier measure of social alienation developed by ?ram (2007, 2009). The scale constructed for this study was comprised of 15 items. The social alienation scale indicated attitudes toward the society (normlessness), toward other people (distrust), his/her locus of control (powerlessness), and sense of future (meaninglessness). The items of the scale are presented in Table 2 in the Appendix.

Right-wing authoritarianism (RWA). The scale was constructed on the basis of items from Altemeyer's original RWA scale published in his book "The Authoritarians" (Altemeyer, 2006). The score of this RWA scale was not computed in the way the author suggested, but on a 5-point Likert-type scale comprised of 22 items. The RWA scale indicated a high degree of submission to the established, legitimate authorities in society, high levels of aggression in the name of their authorities, and a high level of conventionalism. The items of the RWA scale are presented in Table 3 in the Appendix.

Primary psychopathy. Primary psychopathy measure was extracted from the Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale (LSRP) (Levenson, Kiehl & Fitzpatric, 1995). The primary psychopathy items (16 in number) were created to assess a callous-unemotional style, selfishness, and tendency to manipulate others. The primary psychopathy items derived from the LSRP are presented in Table 4 in the Appendix.

The Cronbach's alpha coefficients indicated an acceptable internal consistency for the primary psychopathy scale, good for the general siege mentality scale and the RWA scale, and an excellent internal consistency for the social alienation scale, and that the scores of all the measures were normally distributed (Table 2).

9. Results

10. a) Correlational Analysis

We wanted to see how the examined composite variables were mutually correlated with the criterion variable within different ethnic samples. It is critical to ensure that the predictor variables do not have differential associations with the criterion variable (general siege mentality) within different ethnic groups. Pearson-product moment correlation coefficients were calculated as a measure of the strength and directions of linear relationships among the examined variables. In Tables 3 and 4 we can see that within different ethnic groups the construct of general siege mentality is positively correlated with social alienation, right-wing authoritarianism, and primary psychopathy. However, we can notice slight differences as to the strength of associations within different ethnic groups. First, the strength of correlation between siege mentality and all predictor variables is the same within the Croatian majority. Second, siege mentality is somewhat more strongly correlated with right-wing authoritarianism and primary psychopathy, and somewhat lesser correlated with primary psychopathy within both the Serbian minority in Croatia and Croatian minority in Serbia. Third, social alienation is correlated with both right-wing authoritarianism and primary psychopathy within Croatian and Serbian ethnic minority groups. V.

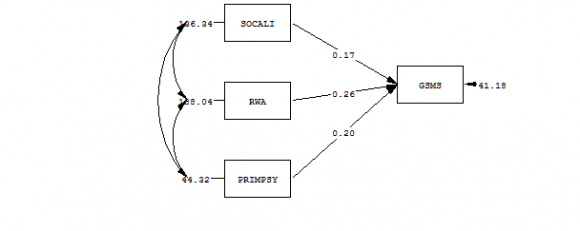

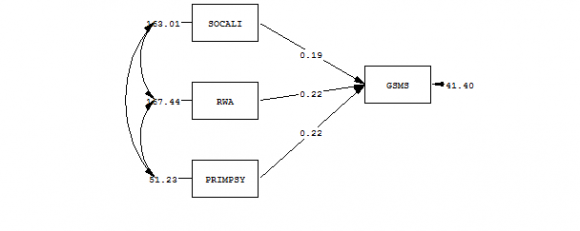

11. Path Analysis

In order to examine whether different ethnic belongings moderated the paths, multiple-group path analysis was employed using the LISREL 8.52 software program for Windows (Jöreskog and Sörbom, 1996). Namely, we wanted to examine simultaneous relationships between multiple observed variables in the hypothesized path model across three ethnic groups. Are certain paths in a specified causal structure invariant across the population, is one of the questions that researchers are typically interested in multi-group invariance analysis (Byrne, 2014). That is the question on which we tried to find the answer in this research.

Croats in Croatia, Serbian minority in Croatia, and Croatian minority in Serbia. Having examined structural model on all three groups jointly and separately for each group, we employed a more formal way to analyze the structural model in which all groups are analysed simultaneously. First, we conducted multi-sample path analysis with no equality constraints on parameter estimates across the groups and then we imposed cross-group equality constraints on the path coefficients. Multiple-group path analysis was employed to examine and test whether differences in the structural parameters across ethnic groups were statistically significant. Testing for cross-group invariance involved comparing two nested models: (1) a baseline model wherein no constraints were specified, and (2) a second model where all paths were constrained to be invariant between the groups. All path estimates (path coefficients interpreted as regression coefficients) were significant, in the expected direction and indicated much similarity in structural relationships (Figures 1, 2, 3). 6. Global goodness-of-fit statistics for unconstrained and constrained model is shown in Table 7. We compared the model in which path coefficients were constrained with a fit of an unconstrained model using the difference in Chi-square statistics. The structural paths for different ethnic groups can be considered identical if Chi-square does not reveal a statistically significant difference between unconstrained and constrained models. In our case, the difference between Chi-square of unconstrained and constrained multiple group path model equals Î?"?2 = 7.1, and the difference in degrees of freedom is Î?"df = 6. With p = 0.31 it can be concluded that difference in path estimates for different ethnic groups are not significant, which means that constrained multiple group model is accepted (Figure 4). Results showed that ethnic belongings did not significantly moderate relations between the variables. About 36% of the variance of general siege mentality was explained by social alienation, right-wing authoritarianism, and primary psychopathy for the full sample in the accepted constrained model.

12. Group goodness-of-fit statistics

13. Discussion

We examined the previously unexplored relationship between social alienation, right-wing authoritarianism, primary psychopathy, and general siege mentality within Croats, Serbian ethnic minority in Croatia, and Croatian minority in Serbia. Our results show that siege mentality was positively correlated with social alienation, right-wing authoritarianism, and primary psychopathy within all three ethnic samples. Although moderate, the correlations indicate that a more complex sociopolitical-psychological phenomenon is underlying the Bar-Tal & Antebi's (1992a) concept of general siege mentality. Thus, there is an evidence of the existence of social and psychological underpinning of the concept of siege mentality that represents not only the cognitive repertoire but also a potential behavioral repertoire (Bar-Tal & Antebi, 1992b). Our first hypothesis, concerning the effects of social alienation, right-wing authoritarianism, and primary psychopathy on siege mentality, was confirmed. Path analysis was used to estimate structural relationships hypothesized by the model. All path estimates (path coefficients interpreted as regression coefficients) were significant in expected direction in all three ethnic groups. There was much similarity in structural relationships within different ethnic groups. Since "the path model represents the hypothesis of correlated causes" (Kline, 2010, p.105), we might conclude that social alienation, right-wing authoritarianism, and primary psychopathy express the causal effects on emerging general siege mentality across different ethnic groups. The results showed that ethnic belongings did not significantly moderate relations between variables. This is the finding that was unexpected, having in mind different perceived experiences and historic memories of the three ethnic groups. One of the possible interpretations of this finding may be in the fact that "... loss of memories becomes an active construction and reconstruction of the past from the standpoint of the present" (Tileaga, 2013, p. 111) and that memory, "...and different forms of its narration, can constitute a threat to societal cohesion and consensus" (Tileaga,p. 113). In other words, siege mentality need not necessarily be exclusively depending on historical memories, the group's perceived experiences, as argued Bar-Tal & Antebi (1992b).

We have proved that social alienation as an indicator of social and political distrust (Ross, 2011;Seeman, 1959;?ram, 2009), right-wing authoritarianism as a measure of desire for social order (Altemeyer, 1981) that bears resemblance to the hierarchy-related cultural dimension and that can reflect a culture-inclusive orientation (Chien, 2016), and primary psychopathy as an ego defense mechanism (Meloy, 2004) reflect some kind of internal threats within a society that antecede and predict siege mentality. Thus, not only external realistic group threats (outside society) but perceiving internal threats (within society) and personality predisposition contribute to the emerging of siege mentality. Insomuch as social alienation presents the cognitive repertoire of interpreting the intentions and behaviors of other people and political institutions as unsupportive, hostile, self-seeking, dishonest and, as a matter of fact, threatening, we can notice that social alienation resembles the concept of siege mentality in a degree it presents the group members' cognitive repertoire of interpreting the intentions and behaviors of out-groups and other nations as hostile, mistrustful, and threatening. The political-psychological difference in these two concepts is in that that social alienation presents an internal realistic group threat and a weak social control while siege mentality presents an external realistic group threat and a weak national security control. What they have in common is the presence of perceived threat and expression of inherently social beliefs about relationships with other people. But both social alienation and siege mentality signify a collective threat. Perceived collective threat, regardless of be it either internal or external, is alienating and distressing even when these threats are not realized in personal victimization (Ross, 2011).

Both social alienation and authoritarianism are the worldviews that help to establish a personal and interpersonal sense of order, structure, and control (Nicol & Rounding, 2013). Insomuch as the loss of personal control over social world resembles sociopsychologically to social alienation, we could conclude that siege mentality (as a kind of societal threat) fosters right-wing authoritarianism via the mediation of social alienation. Given a bidirectional effect between threat perceptions and authoritarianism, we could argue that authoritarianism fosters siege mentality via the mediation of social alienation. In other words, individuals who are more authoritarian and, at the same time, socially alienated more easily and readily express the cognitive repertoire of siege mentality or national threat perception.

Volume XVIII Issue I Version I A significant contribution of primary psychopathy to siege mentality is in line with research that found out the association between threat perception and high level of psychopathy (Serin, 1991;?ram, 2015). Individuals with high levels of psychopathy have a tendency to attribute hostile intentions to others in their social environments. Given the similarity in psychological meaning of primary psychopathy and siege mentality, in a sense that both constructs signify the attribution of hostile intentions to other people, it was reasonable to expect that psychopathy is underlying siege mentality to a certain degree. Schmidt & Muldoom (2013) found out that threat perceptions are correlated with poorer psychological well-being in the sense that perceived intergroup threat has a consequence for psychological well-being. But, we raised a question why the perceived threat would not be a consequence of a poor well-being? In other words, why we should not expect primary psychopathy as a mental disorder to affect threat perception, i.e. siege mentality? In any case, individual affective and motivational factors are psychological dispositions that should be taken into account when explaining siege mentality, as any other attitude formation (Dinesen, Klemmensen & Norgaard, 2014; Gerber, Huber, Doherty & Dowling, 2010) given the impact of emotion on information processing and perception (Clore & Gasper, 2000). Taking all the findings into consideration, there is an evidence that a more complex and severe political-psychological disorder is underpinning the Bar-Tal & Antebi's concept of general siege mentality than a mere perceived national threat, independently of political-historical context. If implied in a social science research, the General siege mentality scale (GSMS) would be a very useful tool to capture a much wider politicalpsychological meaning than Bar-Tal & Antebi (1992a, 1992b) supposed the scale could capture. We should be very cautious when using intergroup threat theory posed by Stephan & Renfro (2002) in explaining various social and political issues, because deep-seated social, cultural, political, and personality disorders may be underpinning perceived threat. We also wish to address some limitations of our research. Limitation of our research is that our data are cross-sectional. That is why we cannot draw confident conclusions about the nature of causality. Our findings should be replicated in future research in other contexts and ethnic groups.

| Sociodemo graphics | ||||

| Ethnicity | Sex | Age | School | Attainment |

| Ethnicity | 1.00 | |||

| Sex | -0.05* | 1.00 | ||

| Age | 0.03 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| School attainment | -0.06* | -0.01 | -0.16** | 1.00 |

| *p=0.05, **p<0.01 | ||||

| III. | ||||

| Composite |

| Predictor variable | Croats | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 1 General siege mentality | 1.00 | |||

| 2 Social alienation | 0.38*** 1.00 | |||

| 3 RWA | 0.38*** 0.06 | 1.00 | ||

| 4 Primary psychopathy | 0.37*** 0.31*** 0.03 | 1.00 | ||

| **p<01, ***p<0.001 | ||||

| Social and Psychological Underpinning of the Bar-Tal and Antebi's Concept of General Siege Mentality | |||||||||

| within Different Ethnic Groups | |||||||||

| Year 2018 | |||||||||

| 4 | |||||||||

| ( C ) | |||||||||

| -Global Journal of Human Social Science | Predictor variable | Serbian minority | Croatian minority | ||||||

| in Croatia | in Serbia | ||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 1 General siege mentality | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 2 Social alienation | 0.45*** 1.00 | 0.45*** 1.00 | |||||||

| 3 RWA | 0.44*** 0.33*** 1.00 | 0.54*** 0.35*** 1.00 | |||||||

| 4 Primary psychopathy | 0.30*** 0.20** 0.29*** 1.00 | .26*** 0.24*** 0.06 1.00 | |||||||

| © 2018 Global Journals | |||||||||

| Model | Chi-Square | df | NFI | CFI | RMSEA | R² |

| Constrained | 8.39 (0.39) | 8.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.01 | 0.36 |

| Unconstrained | 1.35 (0.51) | 2.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.38 |