1. Introduction

ob Satisfaction upheld as a source of profitability and organisation's effectiveness (Aronson, Laurenceau, Sieveking, & Bellet, 2005), continues to attract attention and consensus among researchers who view it as an index of the affective responses of personnel in the workplace (Oshagbemi, 2003;Shallal, nd). This concept has in a special way been of interest to both administrators and researchers (Sekaran, 1989), since Happock's seminal work in 1935 in which job satisfaction investigations have received keen reflections Authors ? ? ?: Busoga University and Lecturer, Iganga, Uganda. in disciplines like psychology, sociology, and economics (Argyle, 1989;Hodson, 1985;Hamermesh, 2001). This concern arises from a number of empirical revelations: satisfied workers are more productive (Appelbaum & Kamal, 2000); deliver higher quality of work (Tietjen & Myers, 1998); and improve on a firm's profitability, spur firm competitiveness and success (Garrido, Perez, & Anton, 2005;Aronson, Laurenceau, Sieveking, & Bellet, 2005).

Many researchers have considered delegation as an approach that improves job satisfaction (Noblet & Rodwell, 2009;Agarwal & Hauswald, 2009). Based on this, delegation of authority helps to overcome distance related obstacles to corporate-decision making through subjective intelligence and permits employees to be satisfied on their jobs. Similarly, studies by (Schriesheim, Neider, & Scandura, 1998;Muindi, 2011), earmark delegation as an important component and predictor of job satisfaction. In recent decades, the level of awareness towards delegation has increased drastically and has gone to its climax to become a wellestablished field of study (Bozkurt & Ergeneli, 2012; Bass, 1990) due to: need to improve the speed and quality of decisions, reduce manager overload, enrich the subordinate's job, increase the subordinate's intrinsic motivation, and provide opportunities for subordinate development of leadership skills, all of which have a bearing on the job satisfaction levels.

In response to the above necessity and the requirement to facilitate attainment of job satisfaction by employees, many organizations are undertaking delegation as an approach for achieving worker's job satisfaction, hence leading to improved service delivery, higher productivity and reduced labor turn over (Muindi, 2011). As earlier pointed out, past studies on the relationships between delegation and job satisfaction have showed significant and positive results (Noblet, 2003;Muindi, 2011;Schriesheim, Neider, & Scandura, 1998). Though there is considerable literature available that have evolved to examine the link between delegation and job satisfaction world over, still little is known about the effect of delegation on employees' job satisfaction from Uganda, particularly within the context of Uganda's primary education service sector. Still, there is paucity of research on how delegation acts as a criterion in influencing job satisfaction. The few existing studies on Ugandan scene like that of (Kyarimpa, 2010), gravitates on secondary school teachers and not those offering basic education. This is an indication of a knowledge gap to which this study aspires to fill. The Ugandan primary education service sector is therefore, considered to be one of the vital and integral component of Uganda's economy. As a consequence, it is for this reason that Universal Primary Education policy has been adopted. Thus, studying the link between delegation and job satisfaction is necessary as it provides a theoretical as well as a practical platform to the education service industry's efforts to improve the performance of primary education sector.

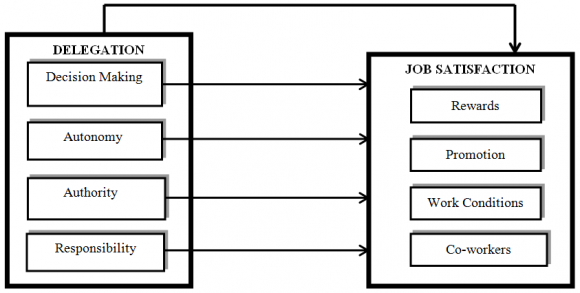

In order to bridge the gap and provide education industry with practical support in appropriately managing and implementing the delegation function to achieve job satisfaction, this study proposes a conceptual model (Fig. 1) of job satisfaction (J.S) particularly within the context of Uganda's primary education service sector, to examine whether the implementation of delegation result in job satisfaction. Therefore, the scope of this study is in finding out the relationship between the delegation and job satisfaction in the primary education service industry and more precisely, the Ugandan education service industry. Given the above reasons, the objectives of this study are twofold:

?2. Delegation

Delegation is conceptualised as a process that involves assigning important tasks to subordinates, giving subordinates responsibility for decisions formally made by the manager, and increasing the amount of work-related discretion allowed to subordinates, including the authority to make decisions without seeking prior approval from the manager (Yukl & Fu, 1999). It occurs when the manager gives an individual the authority and responsibility for making a decision of certain activities, where prior approval may not be required before the decision can be implemented (Yukl G. , 1998;Bass, 1990;Jha, 2004). Associated with delegation are key dimension such as authority, responsibility and accountability (Mullins, 1993). This conceptualisation is based on Stewardship Theory that draws from sociology and psychology disciplines (Hernandez, 2012). This theory is all about trust. Based on this, top managers develop trust in subordinates before they assign them authority and power. Stewardship reflects an on-going sense of obligation or duty to others based on the intention to uphold the covenantal relationship (Davis, Schoorman, & Donaldson, 1997). a) Job Satisfaction Satisfaction has been widely studied in the relevance to the physical and mental well being of the employee, as well as its implications for such job-related behaviours as productivity, absenteeism, turnover and employee relations (Eyupoglu & Saner, 2009;Martins & Coetzee, 2007). Job satisfaction describes an individual's general attitude toward his or her job (Robbins, Odendaal, & Roodt, 2003). Price (1997) defined job satisfaction as the degree to which employees have a positive affective orientation towards employment. Job satisfaction has been conceptualised to involve the dimensions of rewards, promotions, work b) Decision Making and Job Satisfaction Decision making can be defined as choosing between alternatives (Yukl & Fu, 1999). Empirical investigation such as that of the Australian police officers (Noblet & Rodwell, 2009) established that individuals entrusted with more decision-making latitude and support from supervisors and co-workers are more satisfied with their jobs. Further links between decision making and job satisfaction have been synonymous with studies of (Copur, 1990;Nienhuis, 1994). Review of extant literature above; reveal a direct link between decision making and job satisfaction. However, as to whether decision making is linked to job satisfaction within the context of primary school sectors is Uganda, is elusive. Based on this, it is hypothesised that: H1: There is a significant positive relationship between decision making and job satisfaction i. Subordinate's Autonomy and Job Satisfaction Autonomy is deciding what to do in work place (Noblet & Rodwell, 2009). A study done among Australian police officers demonstrated a strong relationship between autonomy and job satisfaction (Noblet & Rodwell, 2009). Also, study by (Thassanakulphan, 1998) on the interrelationship among work motivation, job autonomy, and job satisfaction of full-time employees revealed a strong correlation between autonomy and job satisfaction. While literature considers the direct and indirect links of autonomy and job satisfaction, the extent to which autonomy influences job satisfaction within the context of Uganda's primary sector, is not clear.

This study, investigates this. Hence, it is hypothesised that: H2: There is a significant positive relationship between autonomy and job satisfaction ii. Subordinate's Authority and Job Satisfaction

The results of a survey on the relationship between quality of work life in which delegation of authority was one of the key constructs, and job satisfaction as a criterion variable confirmed that some meaningful association between delegation of authority on job satisfaction in organizations (Mohammadia & Shahrabib, 2013) exist. Further, according to (Agarwal & Hauswald, 2009) in their study of how the allocation of authority affects the production, transmission, and strategic use of subjective intelligence, found that a considerable link between delegate of authority and job satisfaction. This is because delegation of authority helps to overcome distance related obstacles to corporate-decision making through subjective intelligence which inevitably makes employees satisfied on their job. Though studies reviewed established a relationship between delegation of authority and job satisfaction, how delegation of authority influence job satisfaction within the context of Uganda's primary education sector, cannot firmly be ascertained. Hence necessitating a study. Based on this, it can be hypothesised that: H3: There is a significant positive relationship between delegation of authority and job satisfaction iii. Subordinate's Responsibility and Job Satisfaction Assignment of responsibilities is an essential subordinate's responsibility which is a key attribute of delegation, predicts job satisfaction. Also people who take responsibility for the jobs assigned to them by their supervisors, have an opportunity to learn how to work with their bosses, hence leading to job satisfaction. The granting of freedom to act by superior is evidence of confidence in the subordinate. The subordinate responds by developing a constructive sense of responsibility (Rao & Narayana, 1997), which has a bearing in the overall job satisfaction. Studies have indicated that responsibility predicts job satisfaction (Chapman, 2005;Rao & Narayana, 1997). However, the extent to which job satisfaction is predicted by subordinates' responsibility within the realm of Uganda's primary school sector is still unknown. Therefore, this study hypothesises that: H4: There is a significant positive relationship between delegation of authority and job satisfaction.

3. III.

4. Materials and Methods

5. a) Design, population and sample

This study employs a cross sectional survey design. A total sample of 247 primary school teachers was generated using Yamane's (Yamane, 1967) sample size determination approach from a total population of 650. Two hundred and eight (208) questionnaires were received from respondent indicating a response rate of 84%. The unit of analysis was the individual primary school teachers. In terms of gender, the male respondents constituted 76% and the female respondents were 34%. Out of 208 respondents, 130 had Grade Three Certificates; 70 diplomas, 08 had degrees. More than half of the respondents were above 25 years of age.

6. b) Measures of Study Constructs

Delegation was measured consistent with the works of (see, (Mullins, 1993; Schriesheim, Neider, & Scandura, 1998) to involve decision making, autonomy, authority, responsibility, and accountability anchored on Likert scale of 1 to 5 designed to measure the opinion or attitude of a respondent (Burns & Grove, 2009). We did this considering the view that studies were deeply opined by theories identified in this study and also because our analysis tools employed in this study are theory based. However, we considered only four dimensions of decision making, autonomy, authority, and responsibility which were more closely tied to this study.

For the case of Job Satisfaction, the Job Satisfaction Survey, a 36 multi-dimensional instrument developed by Spector, in 1985, was used to measure job satisfaction. The facets were re-arranged without distorting its composition. These are: rewards, promotion, supervision, recognition, work conditions, and co-worker.

7. c) Statistical modelling

We used Structural equation modelling (SEM) to estimate the research model. Structural equation modelling (SEM) is an all-inclusive statistical approach used to test hypotheses about relations among observed and latent variables Black, Babin, Anderson, & Tatham, 2006). SEM helps in understanding relational patterns among a group of variables. Therefore, in order to provide explanation for variation in job satisfaction, this study employs SEM with AMOS. We used the estimation procedure in AMOS 20 (Arbuckle, 2009) to estimate a job satisfaction model among Uganda's primary school teachers. The Chisquare test which is an absolute test of model fit demands that the model is rejected if the p-value is < 0.05; Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) should be < 0.06 and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) values of 0.95 or higher in accordance with (Hu & Bentler, 1999) recommendations. The school of thought of the likes of (Yang, 2006) recommend Goodness of Fit (GFI) > 0.90, Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI) > 0.85, TLI > 0.95, CFI > 0.90 and RMSEA < 0.08 as acceptable goodness-of-fit indices. We relied on these criteria in estimating or fitting our model.

8. IV.

9. Results

The results of our analysis indicated a significant relationship between Decision making, Autonomy, Authority, Responsibility and Job Satisfaction amongst primary school teachers in Uganda's primary schools as can be discerned from Figure 1 and Table 2. The Job Satisfaction model suggested in this study indicated an NFI of 0.965, which indicates strong convergent validity (Mark & Sockel, 2001). The Chisquare value of 16.168 is non-significant at the 0.05 level: its p-value is 0.371, an indication that the model fits the data adequately in our population. Further support is provided by the RMSEA = 0.020 which is further confirmed by the TLI value of 0.996, IFI =.997, CFI = .997. Furthermore, both GFI = 0.978 and AGFI = 0.959 are greater than 0.9 which reflects a good model fit. Therefore, Job Satisfaction model is confirmed for the case of primary school teachers in Uganda.

The standardized and unstandardized loadings in Table 2 appear together with a critical ratio, and pvalues. The critical ratio and p-values were used to determine the level of statistical significance. A critical ratio greater than 1.96 or a p-value smaller than 0.05 illustrates significance. Three asterisks (***) demonstrate that the p-value is lower than 0.001. In this case, all of the unconstrained estimates are significant.

In order to determine the most important paths among study constructs, it became necessary to consider standardized paths. The association or causal paths can be examined based on statistical significance and strength using standardized path coefficients that normally range between -1 and +1 (Hoe, 2009). The standardized paths should be at least 0.20 and preferably 0.3 so as to consider such a path significant or consequential for discussion (Chin, 1998). We present both unstandardized and standardized path coefficients. Three (3) out of the Four (4) path coefficients were statistically significant (p < 0.001). However all the path coefficients for the demographic variables were statistically not significant (p > 0.05). Based on this, we highlight results or findings. Table 2 below indicate unstandardized and standardized paths respectively of the hypothesized model.

The convergent validity was evaluated by examining factor loadings. The observed factor loadings compared with their standard errors showed evidence of an association of different construct items (Koufteros, 1999). As shown in Table 2, the observed factor loadings of all the items are statistically significant at the 0.01 alpha levels. As for item reliability, the multiple (Koufteros, 1999) and was above the suggested minimum of 0.5 (Bollen, 1989). Construct reliability examines the degree to which the measurement of the set of latent items of a construct is consistent (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, & Tatham, 2006) and the construct reliability of job satisfaction was 0.863, 0.897, 0.898 and 0.877 for decision making; autonomy, authority, responsibility. These values were above 0.7 indicating adequate construct reliability (Kim, 2007). Discriminant validity is assessed using Average Variance Extracted (AVE) which should be above 0.5 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). In this study, it is above 0.56 for all study constructs which indicates satisfactory convergent validity. 2 above, hypotheses (H2,H3, and H4) are accepted based on the suggested criterion above, that is standardized path coefficient ( > .2) and the level of statistical significance ( p < .05) while hypothesis (H1) is rejected. The negative and none statistically significant path coefficients of gender and Age in Fig 2 in the Job Satisfaction model (-0.046 p = 0.054; -.013 p = 0.580 respectively) demonstrate that gender and Age differences have no role in Job Satisfaction of primary school teachers. Therefore, it can be inferred that the association of predictor variables (decision making, Chi-Sq. 16.168; p = .371; RMSEA = 0.020; TLI = 0.996; IFI = 0.997; CFI = 0.997; GFI = 0.978; AGFI = 0.959 Autonomy, Authority and Responsibility) in the model and the endogenous variable (Job satisfaction) is significant regardless of Age and gender effects or when the effects of both Age and gender are controlled for.

Similarly, these results demonstrate that Age and gender differences have no effect on Job Satisfaction of Primary school teachers.

V.

10. Discussion

This section discusses results in accordance with the order of hypotheses stated for this study. Save for Decision making, this study established an existing relationship between delegation dimensions of: Autonomy, Authority, Responsibility, and Job satisfaction. This finding is consistent with studies of (Noblet A., 2003;Mohammadia & Shahrabib, 2013;Agarwal & Hauswald, 2009) in which Delegation emperical referents of Autonomy, Authority and Responsibility were found to immensely predict Job satisfaction in organizations. Autonomy is apparent in situations where primary school teachers have control over sequencing of their activities such as lesson planning and work scheming, relative control over their outputs in relation to the objectives and above all freedom in performance of their tasks. According to (Chapman, 2005) assignment of responsibilities strengthens subordinate -superior relationship thereby cultivating an essential environment sufficient to permit Job satisfaction. In line with this, the study established that when primary school teachers were assigned responsibilities such as class teachers, Heads of departments, games masters/ mistresses among others, they ensured and maintained standard performance in their respective responsibilities, assumed liability for any resulting omission and above all nursed a feeling and obligation to steer the organization forward, determine future direction and group accomplishment. These attributes have a positive bearing on Job satisfaction of primary school teachers.

Agarwal and Hauswald (Agarwal & Hauswald, 2009) argued that the allocation of authority affects the production, transmission, and strategic use of subjective intelligence and established a considerable link between delegation of authority and job satisfaction. This is because delegation of authority helps to overcome distance related obstacles to corporate-decision making through subjective intelligence which inevitably makes employees satisfied on their job. Based on this, in primary school setting, teachers have been allowed opportunity to participate in decision making, assessment of their own performance based on agreed performance indicators, and to implement activities in line with organization philosophy without any un due interference from their superiors, a situation that has cultivated an environment for Job satisfaction among primary school teachers.

Interestingly however, this study established that Decision making has no significant impact on the Job satisfaction of primary school teachers. This finding is in variance with studies by (Copur, 1990;Nienhuis, 1994;Agarwal & Hauswald, 2009); who established that individuals entrusted with more decision-making latitude and support from supervisors and co-workers are more satisfied with their jobs. The possible explanation for this inconsistence is perhaps due to the existing structures in primary school sector that do not formally accommodate or provide for leadership provisions among primary school teachers as many of them are perennially relegated in classrooms tasked with teaching responsibilities rather that administration where they would have been more placed to take critical decisions.

11. Implication and Limitations for the study

The findings have important implications for Job satisfaction in Uganda's primary school sector. First, given the recognition that Uganda's Education service sector contributes immensely to its development endeavors, the government and other stakeholders like development partners need to develop an enthusiastic interest in the degree to Job satisfaction in primary sector as predicted by Delegation (Autonomy, Responsibility and Responsibility) as espoused by our fitted structural Job satisfaction model. Furthermore, considering the fact that Job satisfaction model among primary school teachers in Uganda was fitted, It is our considered opinion that our model of Job satisfaction can also apply to other sectors of Uganda's firms, if, once this is done, the problem of less Job satisfaction as evidenced by the high labor turnover among primary school teachers in Uganda's primary school sector could be solved and therefore improve the performance of primary school teachers and schools accordingly. This research can also be of value to other service sectors like secondary education sector, Health sector with similar social -economic conditions. Finally the present study contributes to the ravaging debate and literature on Job satisfaction but from a perspective of primary school teachers in Uganda's context.

A number of limitations accompany this present study. Despite the fact that there is sufficient literature on Motivation, there is scarce literature on Job satisfaction especially within the context of Uganda's primary school sector and this may have limited our conceptualization of the study. Secondly, our study was limited to the primary school sector in Eastern Uganda and it is therefore likely that our results are only applicable to this setting in Uganda. Finally, the present study is cross-sectional and therefore it is possible that the views as given by individuals may change or vary over time. However, irrespective of these limitations, it is our considered opinion that this study makes important contributions as revealed in this paper. Future research may wish to test our model in predicting Job satisfaction