1. INTRODUCTION

risons are fundamentally, institutions known to be a means of punishment by confinement and deterrence for deviants and criminals, through conviction by the Justice System and subsequently incarceration. However incarceration in prisons also has as mission to allow reformation and rehabilitation for detainees and instead deter recidivism. Moreover, according to the United Nations (UN) Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (SMR) it has been made clear that "the purpose and justification of a sentence of imprisonment is ultimately to protect society against crime, and that this end can only be achieved if the period of imprisonment is used to ensure, so far as possible, that upon returning to society the offender is not only willing but able to lead a lawabiding and self-supporting life" (SMR, R.58).

Author ?? ? : University of Technology, Mauritius.

Huge investments to reform prisoners seem to be sunken money as repeat offending appears to be on the rise as it will be seen in section 3 of this paper.

According to United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2006), "Social reintegration in the prison setting refers to assisting with the moral, vocational and educational development of the imprisoned individual via working practices, educational, cultural, and recreational activities available in prison. It includes addressing the special needs of offenders, with programmes covering a range of problems, such as substance addiction, mental or psychological conditions, anger and aggression, among others, which may have led to offending behaviour." Mauritius is a developing country, signatory to UN guidelines where no serious study has yet been undertaken concerning recidivism and its consequences. In spite of many efforts it seems that prisons in Mauritius, as would probably be the case in many other societies, seem to be falling short of their mission. In fact, 85% of detainees (Source: Mauritius Prison Services, 2011) incarcerated in the Republic of Mauritius in year 2009 are persons who have been convicted and incarcerated for a 2 nd to a 5 or more time. Thus, these detainees are persons who can be categorised as 'recidivists'. Recidivists are persons who are engaged in recidivism -a term originating from the Latin recidere, which means to fall back. Recidivism is often used interchangeably with other terms such as repeat offending or re-offending. In the case of this paper, we analyse the extent of recidivism as per secondary data provided by the Mauritius Prison Services (M.P.S) and the Central Statistical Office (C.S.O), which are both governmental agencies. The use of facts and figures provided government agencies does bear the risk of inducing bias into analysis and has limitations; however, their interpretation has revealed interesting findings. This paper considers incarceration and its subsequent side effect recidivism as a lost potential as a reason of the amount of efforts and investment consented. In doing so, the paper which is an exploratory study succinctly reviews the literature on recidivism and the critically assesses the impact of re-integration measures. Section 3 assesses the extent of the problem of recidivism in Mauritius to make a case of lost potential for the economy and society. Section 4 brings some insight into the possible causes and socio-cultural obstacles to reintegration which could palliate the problem of P recidivism while Section 5 draws some relevant conclusions whilst indicatively pointing towards the need for new models to tackle such a problem for the good of the Mauritian economy and society.

II.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW: OVERVIEW OF THE RECIDIVISM AND RE-INTEGRATION THEORIES

a) Employment-Focused Re-integration Programs Recidivism is not a new concept in criminology. It is defined as a relapse into criminal behaviour. Maltz (1984) describes recidivism as 'the reversion of an individual to criminal behaviour'. Recidivism comprises a common theme and is generally used for describing repetitious criminal activity, and a recidivist offender is an individual who engages in such activity. Though no exact measures of this exist, re-arrest and reincarceration are regarded as the best estimate in correctional data. The human, social and financial costs of recidivism are enormous. Although the relationship between crime and employment is complex, most experts seem to agree on some points which are discussed in the paper. It must be added at this point that it is indeed noteworthy to observe that, the fact that ex-detainees tend to struggle in the labour market and frequently end up back in prison does not necessarily mean that employment will reduce recidivism. It is believed that the most promising re-integration models provide coordinated services both before and after offenders are released; but it appears difficult to increase employment and earnings for apparently disadvantaged and prejudiced persons. However, such initiatives have to be undertaken on two main grounds, firstly from a Human Resources perspective, in sense of avoiding wastage of Human Resources or Human Capital and secondly in order to avoid recidivism and the social, economic and financial costs associated with this phenomenon. It is these offenders who are the subject of much debate as they have become variously described throughout the literature as 'chronic', 'multiple', 'frequent', or 'prolific' offenders, among others.

One of the earliest and most frequently cited recidivism studies was conducted in Philadelphia, in the USA (Wolfgang, Figlio & Sellin 1972). The authors used a longitudinal cohort methodology with official police arrest data to measure the frequency of offending among nearly 10,000 males born in 1945. The authors found that by the age of 18, only 35% (n=3,475) had been arrested by the police at least once, but that these offenders had accounted for more than 10,000 episodes of arrest, giving an average of almost three arrests per offender. However there are both theoretical arguments and empirical evidence from studies to support the notion that crime is linked to unemployment, low earnings, or job instability as averred the studies and research by Bernstein and Houston (2000); Sampson and Laub (2005) and Urban Institute Justice Policy Centre (2006). Legitimate employment may reduce the economic incentive to commit crimes, and also may connect ex-detainees to more positive social networks and daily routines. Qualitative data such as that of Nelson, Deess, and Allen (1999) also suggest that finding a job is the highest priority for prisoners upon release. Furthermore, the work of Travis (2005) has raised the attention of policymakers and the public who have both begun to focus on the prisoner re-entry issue, and there is a renewed willingness to spend some money on rehabilitation services. Nevertheless, the surge of interest generated by the researches could easily dissipate, without solid evidence that the rehabilitation and support services make a difference in the re-integration of ex-detainees. After all, there is significant underlying scepticism about the efficacy of rehabilitation efforts from mainstream society perhaps due to the negative portrayal of the ex-detainees or detainees by the mass media. On the positive side, the re-entry domain has an integrated advantage over the welfare domain. Incarceration costs are so high that even small reductions in recidivism could easily produce budgetary savings that outweigh the cost of rehabilitation and support services. b) Incarceration, Education, Skills Building, Employment and Recidivism

Many researches have indicated that employment is a central component of successful reintegration (Laub, Nagin, & Sampson, 1998;Sampson & Laub, 1990. It seems that connections made at the workplace may serve as informal social controls and an instrument of value consensus and cohesiveness that helps to prevent criminal behaviour. For former detainees, employment is correlated with lower recidivism (Rossman & Roman, 2003;Visher, Debus, & Yahner, 2008) and rates of return to prison can be significantly reduced by participation in work readiness programs (Buck, 2000;Sung, 2001). Although recent studies have indicated that workoriented programs can have a significant impact on the employment and recidivism rates of men (Bushway & Reuter, 2002), vocational and educational programs are often unavailable in prisons, and their availability has declined (Lynch & Sabol, 2001). Gainful and stable employments are among the key predictors of desistance from criminal and deviant behaviour that can be directly addressed through a proper sentencing policy or programming in prison. Accordingly, many reentry initiatives have typically focused on preparing returning prisoners to re-enter the job market. Re-entry services often include interventions directly related to skill acquisition to improve labour market prospects such as job readiness, training and placement programs. Although about two thirds of prisoners Trends in Incarceration and Recidivism in Mauritius -Raising the Alarm Global Journal of Human Social Science Volume XI Issue VII Version I below national averages for the general population (Andrews & Bonta, 2006), and the stigma associated with incarceration often makes it difficult for them to secure jobs following release (Bushway & Reuter, 2002;Holzer, Raphael, & Stoll, 2006).

When former prisoners do find jobs, they tend to earn less than individuals with similar background characteristics who have not been incarcerated (Bushway & Reuter, 2002). Thus, research from mostly the USA supports and tends to advocate a strong program-focused emphasis on increasing individual employability of detainees through education, skills training, job readiness, and work release programs, both during incarceration and after release. Few such programs have been studied using a random assignment research design. One exception is the evaluation of the Opportunity to Succeed (OPTS) program, which delivered employment services within a set of comprehensive services for drug-using former prisoners, and found that participants were more likely to be employed full-time in the year after release. However, self-reported arrests and official record measures of recidivism showed no differences between participants and controls (Rossman & Roman, 2003). Employed participants in the OPTS program, however, reported fewer arrests and less drug use. Another study of detainees in Tennessee, a state in the USA, who were required to secure either employment or enrol in a training program as a condition of release, found that those who qualified had marginally better outcomes than a matched comparison in terms of controls, while those who failed had significantly worse outcomes (Chalfin, Tereshchenko, Roman, Roman, & Arriola, 2007).

In a meta-analysis examining the impact of employment training and job assistance in the community for persons with a criminal record, Aos, Miller, and Drake (2006) concluded that these programs have a modest, but significant, 5% impact on recidivism. However, in another meta-analysis, using a very similar set of studies and methods, Visher, Winterfield, and Coggeshall (2005) concluded that community-based employment programs do not significantly reduce recidivism for persons with previous involvement with the criminal justice system. Contemporary job assistance and training programs for former prisoners in the USA such as the Center for Employment Opportunities [CEO] (New York), Safer Foundation (Chicago), and Project Rio (Texas) are more holistic in their approach and incorporate other transition services and re-entry support into their programs (Buck, 2000) while maintaining a primary focus on job placement.

Although several rigorous evaluations are underway, the impact of these newer types of comprehensive, employment-focused programs on former prisoners' employment and recidivism rates is not yet known and is still underway. Still, in the USA, adult corrections have a long history of providing programs for education and employment training (Gaes, Flanagan, Motiuk, & Stewart, 1999;Piehl, 1998). Comprehensive reviews of many of the individual program evaluations generally conclude that adult academic and vocational programs lead to modest reductions in recidivism and increases in employment (Aos, 2006;Cullen & Gendreau, 2000;Gaes et al., 1999;Gerber & Fritsch, 1994;Wilson, Gallagher, & MacKenzie, 2000). However, the majority of the evaluations have one or more methodological problems according to Wilson et al. (2000). Despite the high demand for these programs by inmates, participation in these programs declined from 42% in 1991 to 35 percent in 1997 (Lynch & Sabol, 2001). Reasons for these declines include the rapid growth in prison populations in combination with decreased funding for correctional programming, the frequent transfer of prisoners from one facility to another and greater interest in short-term programs such as substance abuse and cognitive-behavioural programs (Lawrence, Mears, Dubin, & Travis, 2002).

Research suggests that correctional education programming is most successful as part of a systematic approach, integrating employability, social skills training and other specialized programming (Holzer & Martinson, 2005). Education and job training for low earners are most successful when they provide workers with credentials that meet private sector demands. Thus, comprehensive programs that provide training, a range of services and supports, job retention incentives, and access to employers are promising, but rigorous evaluations are as yet lacking.

3. c) Current Studies on Attempts to Curb Recidivism

Fortunately, the recent surge of interest in prisoner re-integration in the USA has triggered some new research that should help to build the knowledge base. Three large-scale studies are under way and can be described as follows:

? The Serious and Violent Offenders Re-entry Initiative (SVORI). This is a $100 million federal initiative led by the U.S. Department of Justice. Grants were provided to all states, and the programs funded under this initiative provide a wide range of pre-release and post-release services.

? The Center for Employment Opportunities (CEO) Evaluation. CEO is one the USA's largest and most highly regarded employment programs for ex-offenders. It uses a transitional employment model that places participants in work crews within one week after enrolment, and pays them daily for the hours they work. Staffs identify problematic workplace behaviours and try to resolve them, and then help participants find regular jobs. As part of the Hard-to-Employ evaluation funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, MDRC, in partnership with the Urban Institute, is evaluating the CEO program using a random assignment design. In 2004 and 2005, nearly 1,000 parolees who showed up at CEO were assigned to receive either the core CEO program or a limited job search assistance model, also run by CEO.

The above studies are again still inconclusive; however, preliminary reports for SVORI and CEO have demonstrated that small but noticeable progress in curbing recidivism has been made.

4. III. INCARCERATION AND RECIDIVISM IN MAURITIUS

The Mauritius Prison Services (MPS) under the aegis of the Prime Minister's Office and the Probation and After Care Services of the Ministry of Social Security, National Solidarity and Senior Citizens Welfare & Reform Institutions are the two official instances which deal with detainees and ex-detainees in Mauritius. There is a perception conveyed by the local mass-media that the situation of law and order is deteriorating, hence criminality and deviance is on the rise. However, even if the mass media portrayal of this situation can be flawed and biased, it is perhaps the multiplicity of channels and medium of media which brings into public focus this perception. Nevertheless, the population in the prisons of Mauritius is on the rise. According to the statistics available from the MPS, the number of remand and convicted Detainees (including adult and juvenile, male and female) in the 11 prisons or detention centres in the Republic of Mauritius was respectively for each category namely on remand and convicted at 707 and 1668, thus a total of 2375 as at 17 July 2009. In addition as at May 2010, the total number of detainees stood at 3517 according to the Record Office of the M.P.S. The prisons are so over-crowded that the State has averred of its will to build a new prison.

Furthermore, on the 29 th 1, it can be seen that the rate of imprisonment has been increasing from year 2007 to 2010. Moreover, the category "Two or More" number of previous imprisonment has increased by 27%; this is linked to re-offending and consequently recidivism. It must be said that, while the CSO and the M.P.S collaborate on the collection of facts and figures, each institution does keep its own independent records and compilation of figures. As at May 2010, the Record Office of the M.P.S published the following statistics on recidivism (See Chart 1) and which shows the level of recidivism, perceived by its trend as being acute and which at present is our main concern.

5. Global Journal of Human Social Science Volume XI Issue VII Version I

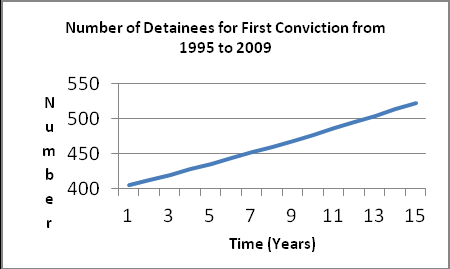

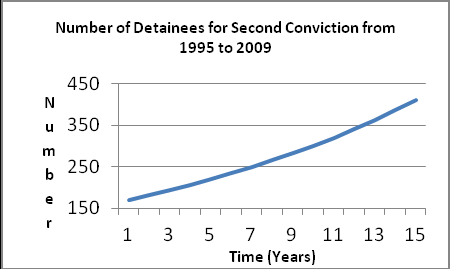

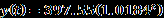

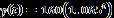

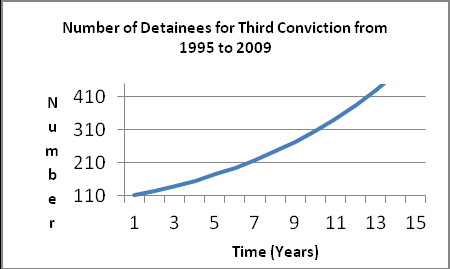

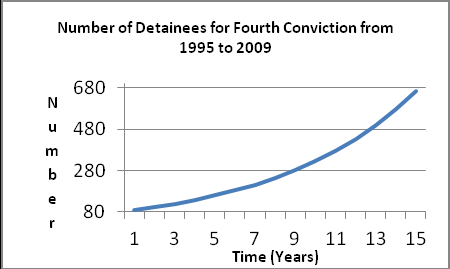

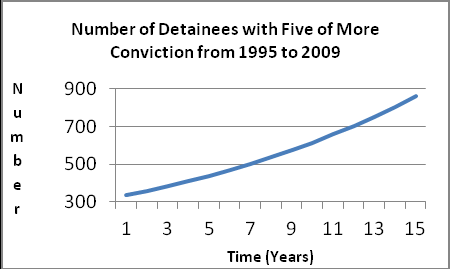

Source : M.P.S Website (2011) An analysis of Chart 1 shows that the sum of detainees incarcerated on a 2 nd or more conviction for year 2010 is 3035 detainees out of 3551, thus giving a percentage of 85% of re-conviction, which is quite high. Moreover, an analysis of Chart 1 shows a constant rise in detainees with a 5 th of more conviction as from 2005. These figures are quite high for a small insular island state like Mauritius as compared with the USA, where for example Freeman (2003a) found from Langan and Levin (2002) that: "About 67% of released prisoners are rearrested and one-half are re-incarcerated within 3 years of release from prison." In addition Freeman (2003b) found that: "Rates of recidivism necessarily rise thereafter, so that upwards of 75%-80% of released prisoners are likely to be re-arrested within a decade of release?.. Fifty-six percent of state prisoners released in 1999 had one of more prior convictions; and 25% had three or more convictions." In Mauritius, more than 85% of released prisoners are re-arrested. So, where does the problem lie? Is it society, jobs, the present laws and so on and so forth? While looking back at Chart 1, it can be observed that the rate for 5 th conviction starts to fall as from years 2002 to 2005 which pre-supposes maybe a change in policy and as from year 2005, there was a change in government by prompted by elections and that rate starts to rise as from 2006 to 2008. The Dangerous Drugs (Amendment) Act 2008 was a more strict law which seems to have impacted on the gradient of the rate of re-conviction for 5 th conviction which has peaked ever since. This assertion of the connection between the Dangerous Drugs (Amendment) Act 2008 and the peak in re-conviction which will be seen further in this paper tend to be mostly linked to drug related offences. Figures 1 to 6 relate to the analysis of the trends for the number of male detainees with respect to the number of previous convictions. The various graphs were derived from exponential models (as shown in Table 2) which were found to be produce the minimum mean sum of square errors (MSE) as compared to other models (e.g., linear, quadratic, cubic) From the models, it can be observed that male detainees having at least five convictions are more dominant than those having two, three or four convictions. They are almost in the same number as those convicted for the first time. The above Figures 1 to 2 and using the Exponential Model Formula and , if we assume that t=21, thus year 2015, and with all factors remaining constant we can set ourselves to predict the figures for re-conviction on different counts and thus the incarceration rate for year 2015 as it is elaborated in the following Table 3. From the Table 3, above showing the application of the Exponential Model shown, we expect about 4700 male detainees in the year 2015 in Mauritius, if no viable and sustainable solutions are brought forward and assuming that all factors remain constant or ceteris paribus.

6. Global Journal of Human Social Science Volume XI Issue VII Version I

At this point it would be suitable to analyse the most common deviant acts committed by detainees by referring to Chart 2, from the Record Office of the M.P.S which shows the total number of admission on conviction to Prison (adult male) as per offences from 1995 to 2009.

7. Source : M.P.S Website (2010)

From Chart 2, it can be analysed that the highest figures in terms of admission to prisons by category of offences committed in year 2009 by Adult Male Prisoners is firstly 'Stealing' (1485 occurrences, thus 42% and secondly 'Drugs' (660 occurrences), thus nearly 19%. The category of offence 'Others' is not specified and so will be not taken into consideration presently. Moreover, it can be seen from Chart 2, that over the last 15 years, the trend for conviction has also been mostly for the categories of offences for 'Stealing' and 'Drugs'. It can be assumed that people who steal are people without a gainful employment or as per temptation and opportunity. As for drug addicts, they are often condemned as drug dealers when found in possession of a certain amount of drugs as per The Dangerous Drugs Act 2000 and The Dangerous Drugs (Amendment) Act 2008 of the Republic of Mauritius. It is commonly observed that often, it is the drug consumers or addicts who get caught up in small scale drug dealing so that they themselves can afford their doses. Consequently, as per the above figures, it can be reasonably said that two of the main causes of conviction are 'Stealing' and 'Drugs'.

Moreover, it is not indicated if the offenders as per the category of offence have been incarcerated on 1 st conviction or conviction. However, it can be reasonably assumed that, recidivism is a key characteristic of criminal justice conviction and admission to prisons. Consequently, a question and an assertion can be raised as simply and logically put forward by Freeman (2003c) and which is as follows: "The 2-3 years that many inmates spend in prison and the additional years that some violent offenders are incarcerated provides society with a unique opportunity to alter their behaviour and rehabilitate them to re-enter society and the job market as productive citizens. Ideally, the incarceration experience should change offenders' assessment of the benefits and costs of crime in two ways. It should shift their preferences or values, so that they weigh more heavily the costs of crime on others relative to the benefits to them. And it should change the options or incentives facing them in favour of legitimate work relative to illegal activities. By altering the values and incentives of inmates, the ideal criminal justice system would release ex-offenders who would find work in the legitimate labour market and make a positive contribution to their families and communities rather than return to crime."Furthermore, from Freeman (2003d) "For many men aged 20-40, the prison door is a revolving one. Commit serious crime; get arrested and incarcerated; spend some time in prison; get out; commit more crimes; get arrested and incarcerated; and so on..... Not until men reach their mid-forties does the rate of re-arrest fall noticeably." it would be interesting to analyse the situation in Mauritius with reference from figures provided by the M.P.S in the analysis of convicted male detainees especially males, as per age group. As at May 2010, the Record Office of the M.P.S published the following statistics on incarceration as per age group (See Chart 3) which is as follows :

Source : M.P.S Website (2010) Analysing chart 3, and referring to Freeman (2003d), it can be said that with some equivalence, for men aged 25 years and less than 50 years in Mauritius, the observation and findings of Freeman (2003d) about men aged between 20 years to 40 years coincides. It must be said that, the sample analysed by Freeman will differ from the sample under study in Mauritius in terms of biographical characteristics. However, the trend for a fall in the crime and deviance rate subject for conviction does also correspond for the category of 50 years or more in Mauritius and for Freeman, in the USA, the midforties. Nevertheless, there are some limitations with the comparison with figures from the USA, a developed country and Mauritius, a developing country. However, data and information from the USA is more readily available as compared to Sub-Saharan countries to which Mauritius belongs. Moreover, cross-comparisons in terms of multivariate data such as detailed, digitally available bio-data of convicted detainees is yet to be made available. There exists at present, individual files of convicted detainees which should be analysed individually for a better comparison and possible regressions. This will be reserved for another study. In addition, it must be said that the above findings reinforce the notion that 'Recidivism' is a universal problem still being tackled with its specificities in the USA, while in Mauritius; the problem is still not addressed. The human, social and financial costs of recidivism are enormous and from the preceding it seems that there is significant lost potential for an island economy with only 1.3 million population. The analysis of secondary data, though with its inherent limitations have had the merit to bring in focus the acute problem of recidivism in Mauritius. Although the relationship between crime and reintegration is complex, most experts, as we have seen from the first three sections of this paper, seem to agree that some approaches are this paper, seem to agree that some approaches are possible to mitigate the impact of recidivism and increase the possibilities for reintegration. Mauritius is already a country lacking Human and having to resort to imported labour, thus decreasing recidivism and re-integrating some people in the labour force is quite interesting for the nation itself. While the Economic and Financial cost in incarceration is an ever-increasing burden on the Nation, investing in the rehabilitation of detainees and ex-detainees seems from the international experience to be a venture which can bring return-on-investment.

In addition, the expenses of the State of Mauritius for the upkeep of detainees is one aspect, the Ministry of Social Security does also contribute for the upkeep of the dependents of detainees in terms of pensions and social aids during incarceration of detainees. The preceding is also a cost and an estimate will have to be devised so as to give a better picture of the situation and will be very relevant for another study. However, there remain intangibles which cannot be measured in terms of accounts and costs: the suffering of the family of the detainee, the trauma of victims and subsequent sequels, divorce, adultery, prostitution, labelling of family and children as being related to a detainee. These are huge costs which cannot be measured and are intangible but which are issues to be further explored. This present section will examine and present some views of a small convenience sample chosen in order to give some voices to some stakeholders of the incarceration world. At present as per time limitations and the study still being at an exploratory stage, it can be said that there is dire need for more scientific studies to bring validity and reliability to this present subject being examined. Some preliminary findings are given herein to ring the alarm bell.

The challenges for rehabilitation and reintegration are manifold and start logically from the prison itself. The Social Welfare aspect for the rehabilitation of detainees is a prime aspect, however, a prison welfare officer who preferred to remain anonymous puts it as follows: "It can be said that as things are presently, there has been and is still in the doing the process of pushing detainees who are Humans with their social realities and identities in a Ghetto? There is no second chance being given in the present context where the State has as duty to promote an equal and egalitarian society. Prison could have had a place where one pushes the 'reset button'? There are too many problems and while we want to help? we are not God to be everywhere at the same time? Drug addiction rehabilitation is useless, drugs are available in the prison? and education of detainees is presently an empty slogan?" This statement from a Prison Welfare Officer concurs with Freeman (2003c) in section 3 of this paper.

The Government and the State of Mauritius have a number of other arms, namely: the National Empowerment Foundation, the Trust Fund for the Integration of Vulnerable Groups, the Eradication of Absolute Poverty Programme, and The Decentralised Cooperation Programme amongst others. Are they contributing for the reintegration and rehabilitation of exdetainees? The Civil Society, through the Mauritius Council of Social Services has a number of NGOs which work with ex-detainees. Is their work having an impact? NGOs that work on the rehabilitation of prisoners are mainly as follows: In prison -LOTUS Centreresidential; Outside prison -Males (Groupe Elan, Centre de Solidarite); Females (Kinouete, Chrysalide); Other NGOs/ religious institutions that visit prison: Brahma Kumaris, NATReSA, P.I.L.S. However, as per interviews carried with representatives of NGOs and ex-detainees, some limitations in their ability to bring any significant contribution to social reintegration are immediately apparent:

? According to Lindsay Aza, an ex-detainee and president of Groupe Elan, a NGO at the forefront of the fight for detainees' rights, one of the main obstacles, for gaining employment is the "Morality Certificate" which can be understood as a certificate provided by the Attorney General's Office which after a police enquiry testifies that a person has not committed a crime or an offence for the last ten years, as from the date of their release. The fact that in Mauritius most, if not, all employers require such a certificate is a major obstacle for ex-detainees to get employment.

As one ex-detainee J.P puts it: « meme si mo finne fini paye mo dette envers societe, quand mo finne alle dans prison, sa zaffer qui mo pas gagne certificat moralite ek qui mo finne alle crazer la reste coller lor moi? » A translation of the above could be: "Even if I have paid back my debt towards society by going to prison, the fact that I don't get the Morality Certificate and that I had been convicted remains glued to me?"

? The second major obstacle of re-integration through work, in Mauritius, often brought up by ex-detainees and NGOs is the issue of frozen bank account. A woman P.F, an ex-detainee convicted for drug dealing and mother of a 10 year old girl explained the situation in the following. Even if an ex-detainee succeeds in getting work without a Morality Certificate, there is still the hurdle of the frozen bank account. This can be understood as, for those person convicted to drug related offences (traffickers and consumers) even when they are released, the enquiry conducted in their case is not yet over and as such they do not have access to their bank accounts. The problem becomes dramatic when employers demand a bank account for payment of their salary. If the employer did not know about the employee's, that is, the ex-detainee's past, the frozen ? A third major obstacle formulated by an ex-detainee S.M is the prejudice, bias and stigma which law enforcement agents and police officers have regarding them. detainees talk about being harassed, victimised, and taken to task and being always considered as the usual suspects in many cases by police officers who know about a their convicted past. It is needless to say that, this is one of the worst problems which they have to face.

VI.

8. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The findings of this study are not conclusive as per the small sample size of the interviewees due to time and resources constraints at this present stage. However, these findings are surely indicative of the consequences or collaterals and challenges of recidivism facing Mauritius. There are already signs that if the problems are not addressed at an early stage, the wounds inflicted to the Mauritian Society through recidivism will develop into gangrene. Actions seem to be required especially at the state level in terms of firm and resolute policy decisions to audit the current situation and stakeholders (The Government, Prison Authorities, The Judiciary, The Police Force, NGOs, Employers), may be re-organise and take a fresh start. The laws might have to be re-visited to re-look at discrimination against ex-prisoners along the lines of the fight against gender discrimination or discriminations against HIV positives or handicapped citizens.

Mauritius is a developing country, as such, it is not about a question of re-inventing the wheel, we have since our history as an independent country as far back as in 1968 emulated the models and strategies set forth by different countries. Nevertheless, this country does have its own socio-cultural peculiarities and consequently, what can be developed and practised in this country will tend to seem insular and specific. Nevertheless, it must be said that, just as it is the case for Mauritius, all civilised societies and countries in the world have prisons and ex-detainees. The issue of the re-integration of ex-detainees in mainstream society through one of the main institution of society namely: work, is thus universal. Practical, pragmatic and workable ideas from a Social Policy and Human Resource Management perspective for ex-detainees in Mauritius can also work for different other countries. It must be said that Mauritius is a fast moving country and is on par with the New Economy generated through Globalisation which is prompting for more Tertiary sector jobs in terms of the services and outsourcing industries. Will Mauritius be able to meet the demands of the market in terms of the labour force? Rehabilitation and re-integration of ex-detainees provided with proper training could be viable perspective, by hitting two birds with one stone. This paper will form the prelude for more indepth has examination of issues and alternatives which could be used as a roadmap in the attempt to see if the integration of ex-detainees in the work life of Mauritius, is blocked by obstacles and how, perhaps solutions for a more inclusive and integrated approach will allow exdetainees to become productive members of mainstream society by firstly being allowed to and also be motivated to join the workforce. Although, further studies will be limited to Mauritius, it can be said with a reasonable level of confidence that the findings will be with some adaptations, applicable to many other societies. Even if detainees may only amount to 0.1% of the world population, an understanding and a proper channelling, orientation, and re-integration of exdetainees will indirectly benefit the whole of the world's population and societies.

| of Previous Imprisonment, Republic of Mauritius, | ||||

| Years 2007, 2008, 2009 & 2010 | ||||

| Year | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 |

| No previous 427 | 573 | 541 | 524 | |

| One | 326 | 511 | 464 | 491 |

| Two or more 1,873 | 1,948 | 2,562 | 2,596 | |

| Total | 2,626 | 3,032 | 3,567 | 3,611 |

| Source : C.S.O 2011 | ||||

| From Table | ||||

| where t=16 for analyzing Trend of Male Detainees as | ||

| per conviction | ||

| Figure | Exponential Model | MSE |

| Number | ||

| 1 | 0.014325 | |

| 2 | 0.007011 | |

| 3 | 0.013742 | |

| 4 | 0.025751 | |

| 5 | 0.026178 | |

| 6 | 0.005098 | |

| Incarceration | Incarceration | Actual | % | Predicted | Predicted % | |||

| Conviction Counts | Exponential Model | MSE | Rate -Year 1995 | Rate -Year 2010 | Increase of Incarceration from 1995 to | Incarceration Rates for Year 2015 | Increase of Incarceration from 1995 to | |

| 2010 | 2015 | |||||||

| 1 st | 0.014325 344 | 516 | 50 % | 583 | 69.5 % | |||

| 2 nd | 0.007011 229 | 466 | 103.5 % | 600 | 162 % | |||

| 3 rd | 0.013742 121 | 375 | 209.9 % | 1059 | 775 % | |||

| 4 th | 0.025751 97 | 538 | 454.6 % | 1570 | 1518 % | |||

| 5 th | 0.026178 485 | 1656 | 241.4 % | 1293 | 166.6 % | |||

| Total | 0.005098 1276 | 3551 | 178. 3 % | 4693 | 267.8 % | |||